![]()

PART ONE: THE NATURE OF IRONY

1

Introducing the ironic perspective

Why do efforts to improve the quality of education via organizational leadership and management make matters worse in some respects as well as better? In what ways are education professionals responding to such efforts? Could the endeavour to improve education through organizational leadership and management be rendered more effective by accepting certain limitations in practice on what is desirable in principle? These questions are of considerable significance for education now and in the future, yet they are also contentious. Implicit in the first question is the assumption that contemporary efforts are producing negative as well as positive impacts. The second question raises the possibility that not all educational professionals are responding as would-be improvers might wish. The third question suggests that there are perhaps limits to the potential for improvement at the level of practice that need to be taken into account. These reservations rarely surface in current policy discourse – at least in its public expression, though we suspect that some might be acknowledged privately. For alongside the gains of reform, there is plentiful evidence of problems.

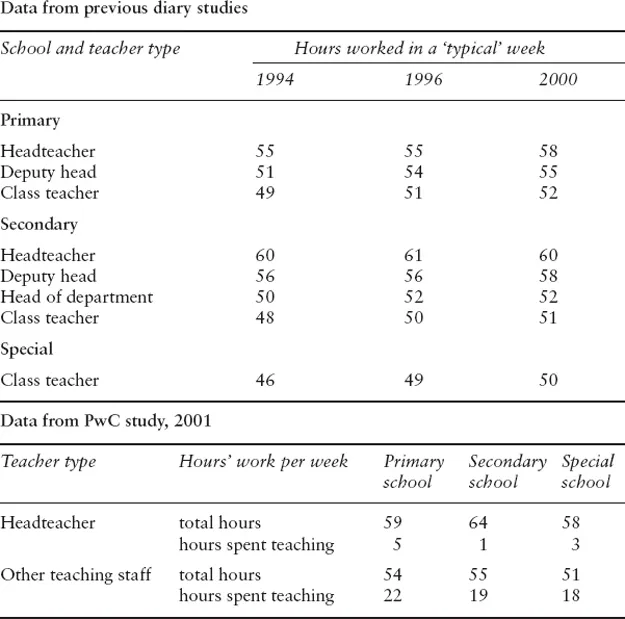

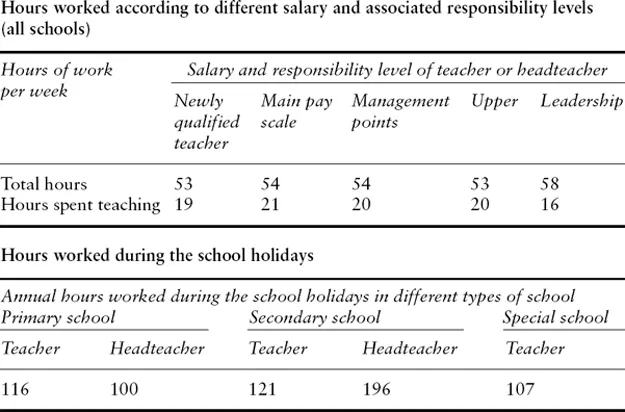

Here is just one indicative example. Heralded by the passing of the Education Reform Act in 1988, successive British governments have generated an extensive series of policies aimed at transforming English state school education as part of a wider strategy to reform, or to ‘modernize’, all the public services (e.g. OPSR, 2002). An unintended negative consequence has been to overload chronically the headteachers and teachers charged with responsibility for implementing the multiplicity of innovations entailed in these policies. Government-sponsored surveys between 1994 and 2000 revealed a steady increase in working hours of those employed in schools (Table 1.1). As a result of pressure from representatives of teachers and headteachers, at the end of the 1990s central government instituted an initiative to reduce the level of bureaucracy in schools that had mostly resulted from its own reforms. However, subsequent surveys showed that the initiative had done little to stem the tide of paper and computer files. One comparative study showed that the annual working hours of headteachers – even after taking the length of school holidays into account – were still above the average for managers across a range of occupations. Weekly term-time hours of headteachers were much higher (PWC, 2001).

Table 1.1: Evidence from PriceWaterhouseCoopers teachers’ workload study

Source: Based on extracts from the interim report of the PriceWaterhouseCoopers teacher workload study (PwC, 2001)

In late 2002, another major survey of the responses of teachers to the demands of their work, sponsored by the General Teaching Council for England and the Guardian newspaper (GTC, 2003), found that:

- approximately one-third (35 per cent) of teachers planned to leave teaching in the next five years, just over half expecting to retire. But the remainder of those planning to leave (including 15 per cent of all newly qualified teachers) expected to secure jobs elsewhere;

- more than half (56 per cent) stated that their morale was lower than when they joined the profession;

- the longer teachers had been in the profession, the worse their morale. However, there was also a sharp dip in morale immediately after the first year of teaching;

- in nominating three factors which demotivated them as teachers, over half (56 per cent) identified ‘workload’ (including unnecessary paperwork), over a third (39 per cent) referred to ‘initiative overload’, about a third (35 per cent) the ‘target-driven culture’ (connected with central government-imposed improvement targets), and almost a third (31 per cent) blamed poor student behaviour and discipline;

- four-fifths (78 per cent) of teachers perceived that the government accorded them little or no respect.

An enduring staff recruitment and retention problem had emerged, created in large part by the heavy workload that was being experienced. Carol Adams, the chief executive of the GTC, commented (GTC, 2003):

Teachers in the 45+ age range constitute half the workforce and represent a significant and valuable resource of experience and expertise. Often, however, their potential contribution is overlooked for a variety of reasons:

- workload has increased to the point that they feel a proper work–life balance is impossible to achieve and some start to look at the option of early retirement or a change of occupation;

- seniority in the profession still tends to be associated with taking managerial responsibility, whereas some would prefer to remain in a teaching post;

- for women returners promotion involving an even heavier workload may not be attractive.

As a result of undervaluing the over-45s, we are not only seeing many experienced teachers go early, we are also failing to tap into their valuable experience of change management, behaviour management and as potential mentors for new recruits. Many of this group of teachers were involved in the school-based innovations which preceded the Education Reform Act of 1988 and they have been instrumental in managing substantial change through the past decade. But instead of valuing what they can offer – we are watching them go.

She noted that according to government statistics one-third of teachers retiring in 2000–2001 had retired prematurely.

If government reforms had produced such consequences for the morale and aspirations of teachers, one can assume that the impact on headteachers was even greater. However, notwithstanding all the reform efforts of policy-makers, and the increased workload of teachers and headteachers, educational outcomes based on qualifications across the UK as a whole have not kept pace with all of its international economic competitors. A recent league table published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2003) compared the proportion of students achieving good qualifications at the end of secondary school in 30 developed countries between 1991 and 2001. The UK had dropped from 13th to 20th in the league because improvement in the UK since 1991 was more modest than elsewhere.

We recognize that survey data are contestable and open to different interpretations. Nevertheless there is strong evidence from a variety of sources that two decades of reform have not led to anticipated levels of educational improvement, and certainly not commensurate with levels of investment in education, but have led to widespread teacher and headteacher dissatisfaction. We regard the gap as ironic. For this reason we have taken irony as our key analytical concept. However, although one side of the coin of irony reveals the gap between intention and outcome in government policy, the other side of the coin reveals how headteachers and teachers have adopted an ironic orientation as a means of coping with the pressures which this gap has generated.

Taking irony seriously

Irony has no canonical meaning. It is a term with a long history in the English language and has diverse connotations. Some are intentionally playful, mocking or cynical, as in Mark Twain’s dictum: ‘To succeed in life, you need two things: ignorance and confidence.’ We realize that taking this term as the centrepiece of our perspective risks us being interpreted as frivolous, and so not to be taken seriously. But we are very serious about improving education. We have chosen to employ this term as the basis for a new perspective because no alternative concept so incisively illuminates the phenomenon we believe needs exploring if government and organization-based improvement efforts are to become more effective. To minimize the risk of being misunderstood, we will below unpack the connotations that we have attached to irony for the purpose of our argument. However, before considering the concept itself, we offer two illustrations of irony by way of setting the scene.

The first is far from education. We have selected it as the most extreme of cases to show how irony is a concept that can direct attention both to coincidences and to unintended cause and effect linkages, including those of the most shocking kind. Perutz (1998) recounts the story of the ‘ambiguous personality and career’ of the German chemist Fritz Haber (1868–1934), a Jew by birth. In 1909 he became the first scientist to synthesize the gas ammonia from nitrogen in the air, paving the way for industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers that dramatically increased worldwide agricultural production, producing the very positive long-term consequence of improving life chances for millions of people.

However, Haber’s discovery also enabled the German manufacture of nitrates for explosives to be continued throughout World War I, after the British naval blockade in 1914 halted supplies of Chilean saltpetre from which explosives had traditionally been manufactured. According to Perutz, without Haber’s invention the Germans would have soon been forced to sue for peace. This invention thus generated the negative consequence of prolonging the war, robbing millions of people of their life chances.

Haber, fervently patriotic, was instrumental in developing poison gas for trench warfare. He helped to mount the first chlorine gas attack which caused some 15,000 allied casualties, a third of them fatal. That night Haber’s wife committed suicide, shooting herself with her husband’s service pistol. Her act was widely interpreted as a protest against his chemical warfare activities.

In recognition of his pioneering synthesis of ammonia, Haber received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918. He continued advising Germany’s government on the secret production of chemical weapons until 1933, when the Nazis seized power. They forced him from his official position because he was Jewish, and he soon fled abroad, dying a year later. He never lived to witness the longer-term consequences of another of his inventions, in 1919: the poisonous gas Zyklon B, originally intended for use against agricultural pests. Nine years after Haber’s death, the Nazi SS chose this gas for deployment at Auschwitz and other Nazi death camps, and among the millions of Jews who were killed in the Holocaust were Haber’s own relatives.

But as Perutz (1998: 16) reflects:

By a terrible irony of fate, it was his apparently most beneficent invention, the synthesis of ammonia, which has also harmed the world immeasurably. Without it, Germany would have run out of explosives once its long-planned blitzkrieg against France failed. The war would have come to an early end and millions of young men would not have been slaughtered. In these circumstances, Lenin might never have got to Russia, Hitler might never have come to power, the Holocaust might not have happened, and European civilization from Gibraltar to the Urals might have been spared.

There is a horrific mixture in this story of the ironies of coincidence and the ironies of unintended consequences, often far removed in time from the actions that led directly or indirectly to them. We move on to a second example, of a very different order from such an utterly appalling case, but which could have serious enough implications for education.

Our second illustration is nearer to home: on 28 April 2003 it was announced that Jarvis, an engineering company, had been awarded a three-year contract from the British government to advise the 700 worst performing secondary schools in England and Wales, through its subsidiary Jarvis Educational Services Ltd. The Guardian (2003) newspaper reported that the announcement was condemned as ‘shocking’, ‘extraordinary’ and ‘a joke’ by teachers’ leaders. Their angry reaction was provoked by the fact that Jarvis had been notably unsuccessful as the main contractor for the privatized national railway network infrastructure. The parent company was at that time under police investigation in connection with the possibility of negligence in the Jarvis railway line maintenance work that might have caused a fatal train crash. It was thus deemed highly inappropriate for Jarvis to be commissioned by the government to ‘re-engineer’ failing schools.

By July 2004 the Guardian was reporting the Jarvis group to be close to bankruptcy. Its Accommodation Services Division was the biggest contractor in the country within the central government private finance initiative for refurbishing schools and universities. Underbidding to win new business had brought the dire unintended consequence of cost over-runs. Jarvis was forced to write them off, plunging the group into debt and threatening to delay much-needed improvement in the education building stock. In the same month, the parent company was heavily fined for negligence over a second rail repair incident described by a judge as ‘breaking basic rules known to every child with a train set’. A freight train had been diverted onto a line with a missing stretch of track.

The award of the advisory contract to Jarvis is emblematic of the ironies of unintended consequences besetting state education in the UK. We contend that such ironies have been generated by unintentionally inappropriate responses to alleged problems. Although greatly increased levels of funding have been allocated to education, it is not evident that members of the public perceive corresponding improvement. There is some evidence to the contrary – witness the OECD international league table mentioned earlier. Although government policy is to give schools greater freedom through policies of devolution and ‘cutting red-tape’, many headteachers and teachers perceive only greater bureaucracy. Although a policy of equality of opportunity is proclaimed, another government policy to create ‘specialist’ schools is creating new forms of selection, and although government ministers have confirmed their intention to recruit and retain high quality teachers, we have already noted evidence of a decline in the job satisfaction of teachers and a drift away from the profession.

These discrepancies appear to stem in part from a lack of understanding among policy-makers about the daily realities of schooling and how the multiple changes they introduce impact on what is already a difficult job. They arise especially from a misguided faith in leadership and management as a panacea. The discrepancy between intention and outcome in relation to policy has been widely discussed in the policy literature. But here we seek to explore the significance of this discrepancy in terms of the experience of headteachers and teachers and its implication for professional work.

The ironic perspective will help us to sustain the argument that the latent function of much recent policy has been to eliminate prevailing ambiguity from educational organizations even though, in our view, much of that ambiguity is endemic. This strategy has entailed the pursuit of greater uniformity over the process and outcomes of education, to be achieved by establishing a much tighter link between official goals, school leadership and management, school structures, school cultures, the technology of learning and teaching, and measured learning outcomes. It is a strategy based on the optimistic Taylorist assumption (to be discussed further below) that the tighter the coupling the greater the efficiency. We accept that there are compelling reasons for reducing ambiguity in schools in order to provide a consistent and incremental education – but only up to a point. We consider that policy-makers have unwittingly tried to reduce ambiguity beyond that point, bringing the ironic consequence of generating increased ambiguity. We also accept that there exist in schools as organizations endemic ambiguities that can neither be ‘managed away’ nor ‘dissolved’ through a ‘shared culture’. Headteachers and teachers live with these ambiguities and cope with them on a daily basis. Over-reliance on managerialism, which seeks to resolve ambiguities in the interests of accountability and on the enforcement of ‘national standards’, has made life difficult for teachers and headteachers. Managerialism diverts teachers from their core task of promoting learning into an expanding range of managerial roles. Some are at best pseudo-managerial, and at worst, could be merely self-serving for their incumbents. Too much leadership and management could be constraining the very educational activity they are there to facilitate.

Despite the unacceptable pressures on headteachers and teachers, a majority remain committed to their vocation. By selectively reinterpreting policy they are continuing to do their best for their students in their immediate circumstances. In this way they are offsetting to some degree the unintended, and potentially deleterious, consequences of managerialism. Ironically this response often ensures that the intention of policy-makers is fulfilled to a degree that would not be possible if specified procedures had been followed to the letter.

An approach to irony

Our approach, then, is to adopt the notion of irony as affording a profitable perspective upon contemporary leadership and management in education. It is a modest approach. Our perspective has neither the rigour of a theory nor the neatness of a model. It has no pretensions to be more than one lens for bringing into focus the implications of the gap between policies and their effects. In using the term we seek to encourage reflection, provoke thought, generate discussion and thereby enhance understanding. Normal academic protocol would require us to define our key term of irony at the outset. Yet no single definition meets our needs. In fact, many who have written on irony have noted the problem of defining the term. Enright (1984), in The Alluring Problem: An Essay on Irony, questioningly heads his first chapter: ‘Definitions?’ Here he cites a remark by Muecke (1969) that ‘getting to grips with irony seems to have something in common with gathering mist, there is plenty to take hold of if we could’. Since there appears to be no canonical definition of irony, we feel at...