![]()

1

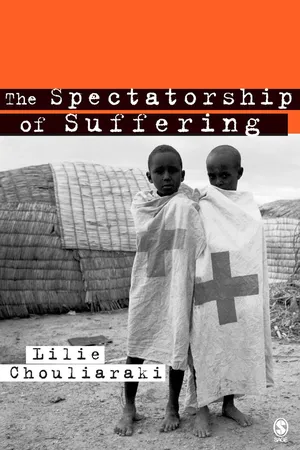

MEDIATION AND PUBLIC LIFE

Confronting Western spectators with distant suffering is often regarded as the very essence of the power of television. This is the power to make spectators witnesses of human pain by bringing home disturbing images and experiences from faraway places. The spectators see and hear about children dying in the refugee camps of the Sudan, the school siege of Beslan or the streets of Gaza, Baghdad and Kabul. ‘You cannot say you didn’t know’: this is television’s mode of address to spectators safely watching the news in their own living rooms.1 No, we cannot say we didn’t know, but can we act on what we now know? What are we supposed to do with our knowledge of suffering? This tension between a knowing yet incapable witness at a distance is the most profound moral demand that television makes on Western spectators today.

This demand also places television’s role as an agent of ethical responsibility at the centre of current debates in media and social theory. The ethical role of television is indeed a controversial matter. On the one hand, there is optimism. The sheer exposure to the suffering of the world, which television has made possible to an unprecedented degree, brings about a new sensibility. It brings about an awareness and a responsibility towards the world ‘out there’ that has previously been impossible to create. On the other hand, there is pessimism.2 The overexposure to human suffering has unaestheticizing, numbing effects. Rather than cultivating a sensibility, the spectacle of suffering becomes domesticated by the experience of watching it on television. As ‘yet another spectacle’ too, suffering is met with indifference or discomfort, with viewers switching off or zapping to another channel. Ultimately, the debate is polarized into ungrounded optimism – spectators’ involvement in distant suffering is possible – and unnecessary pessimism – this involvement is, de facto, impossible.

I now take as my point of departure for this debate on media and social theory a discussion of the two competing narratives on the ethical role of television in social life – the optimistic and pessimistic ones. The main concept in this debate is mediation. The question is how we can study mediation as a public–political process, a process that sets up norms of public conduct and shapes the spectator as a citizen of the world. My own argument is that the potential of mediation to cultivate a cosmopolitan sensibility is neither de facto possible nor a priori impossible – it has its own historical and social conditions of possibility. In order to investigate these conditions, I propose to investigate empirically how television creates sentiments of pity in its news reports on human suffering.

I approach the notion of pity not as the natural sentiment of human empathy but, rather, as a sociological category that is constituted in discourse. Pity is a product of the manner in which television signifies the relationship between spectators and distant sufferers. Pity, therefore, draws attention to the meaning-making operations by means of which sufferers are strategically, though not necessarily consciously, constituted so as to engage spectators in multiple forms of emotion and dispositions to action. ‘In order to generalize’, Boltanski writes, ‘pity becomes eloquent, recognizing and discovering itself as emotion and feeling’ (1999: 6). As the discursive mechanism that establishes a generalized concern for the ‘other’, pity is central to contemporary conceptions of Western public life and indispensable to the constitution of modern democratic societies.3

I propose two particular dimensions of the spectator–sufferer relationship that enable us to analyse the ‘eloquence’ of pity, its production in meaning. These are the dimensions of proximity–distance and watching–acting. How close or how far away are spectators placed vis-à-vis sufferers? How are spectators ‘imagined’ as reacting vis-à-vis sufferers’ misfortunes – look at it, feel for it, act on it?

Using these questions to investigate the ethical impact of mediation helps us break with dominant perspectives on how television should or should not moralize the spectator and allows us to examine how television actually produces its own ethical norms and standards for public conduct. The research practice I am exercising is phronesis – an Aristotelian practice that approaches ethics as the situated enactment of values, rather than abstract principles of conduct.

Mediation

The concept of mediation is often defined in relation to its ethical implications – that is, in relation to the capacity of the media to involve us emotionally and culturally with distant ‘others’. Tomlinson (1999: 154) provides two distinct definitions of mediation, the combination of which highlights the ethical underpinnings of the concept. In the first definition, mediation is about ‘overcoming distance in communication’. As such, it is responsible for the deep cultural transformations of our times. Mediation is responsible for deterritorialization, the overcoming of geographical distance, as well as the compression of space and time and the real-time witnessing of faraway events. Mediation, in this definition, is not only about overcoming geographical distance, but also ‘the closing of moral distance’ between people who live far away from one another.

At the same time, wishing to avoid a naive determinism that celebrates mediation as the happy bringing together of the world, Tomlinson also cares to emphasize the role that the medium plays in closing the distance between disparate locales. His second definition of mediation, then, is about the act of ‘passing through the medium’. This definition draws attention to the fact that everything we watch on screen is subject to the interventions of technology and the semiotic modes that the technology of the medium puts to use. Satellite transmission, strategies of camera work, television’s narratives and genres are some of the techno-semiotic affordances of television that affect the manner in which the closing of the distance between spectator and spectacle occurs.4

These two definitions of mediation – concerning distance and the medium – are brought together because they serve the ultimate purpose, or the telos, of mediation. To connect:

one way of thinking about the development of modern media and communication technologies is as the constant attempt to deliver the promise of the first definition [closing distance, LC] by reducing the problems of the second [refining the medium, LC].

(Tomlinson, 1999: 155)

Tomlinson provides us with a teleology of mediation – a story of progress constantly striving for connectivity. How can the promise of connectivity between places and people be fulfilled? For Tomlinson, mediation connects us by delivering immediacy – one that is qualitatively distinct from face-to-face interaction. Specifically, mediation is about putting technical immediacy – the high fidelity of transmission – at the service of socio-cultural immediacy – the sense of copresence with faraway others. The ethical capacity of mediation rests on immediacy as a certain sense of togetherness or ‘modality of connectivity’ in Tomlinson’s words (1999: 157).

Let us take an example. The European spectator is, in theory, unable to share the same emotional and cultural experience as a Nigerian woman who has been given a death sentence under the sharia law (the case of Amina Lawal in summer 2002). Yet, television’s shocking images of collective violence, showing street scenes of an African woman being mobbed by an enraged crowd of men, facilitate modal imagination. Modal imagination is the ability of spectators to imagine something that they have not experienced themselves as being possible for others to experience. It is not simply impossible or unreal.5 This may sound simple, yet the capacity of television to mediate events from far away as possible and thus factual rather than render them imaginary and fictional is, as we shall see, highly debatable. For now, let me insist that the visual immediacy of such television scenes makes it possible for spectators to perform an ‘as if’ operation. Instead of orienating spectators towards the news on death by stoning simply as an object of their thoughts – a ‘thinking of’ stoning, to use Boltanski’s words, ‘without considering this object to be possible in the real world’ – this ‘as if’ operation triggered by the image permits the spectator to think that stoning is an actual possibility for a woman out there in the world. Boltanski claims:

Thinking that, assumes that one considers [objects of thought] to be possible in a real universe by putting oneself in the state of mind of someone who makes judgements concerning them.

(Boltanski, 1999: 51)

I return to the highly suggestive ‘thinking of’ – ‘thinking that’ distinction and its implications for the moralization of the spectator below. For now, the news about the Nigerian woman suggests that mediated immediacy is about construing proximity – a sense of ‘being there’ that, albeit different from face-to-face contact, evokes feelings and dispositions to act ‘as if’ the spectator were on location.

Mediation, intimacy and politics

Is the involvement of the spectator with a distant other a new theme in the study of mediation? No, it is not. The emotional and practical involvement of the spectator with the distant other has already been studied as the theme of intimacy at a distance.6 This is the spectator’s non-reciprocal feeling of closeness to public personalities. Princess Diana’s appeal for global audiences and the unprecedented reaction to her death are the standard examples given in the relevant literature. For my purposes, using Diana as an example raises the question of how spectators are able to sustain a certain emotional orientation towards a person unknown to them and suggests that such an emotional orientation involves a constant tension in the spectator–celebrity relationship. This is the tension between spectators feeling close to their idols while, simultaneously, knowing that it is impossible to establish physical contact with them. In this sense, intimacy at a distance expresses both tensions of mediation. It expresses the tension between proximity and distance – feeling close but unable to approach the person – and between watching and acting – seeing the idol on screen, but being unable to do something with or for that person.

The theme of intimacy at a distance, however, cannot conceive of these tensions of mediation as fundamentally ethical ones, because the spectator – celebrity relationship does not entail the same radical asymmetry as the spectator – sufferer relationship. Tester describes this asymmetry as ‘an imbalance in the material relationship between the audience which reads the newspaper or watches the television and the suffering and miserable other on the page or the screen. [Whereas] the audience is in a position of relative leisure and safety, the suffering other is in a position of frequently absolute destitution’ (2001: 78).

My focus on the spectator–sufferer relationship rests on the assumption, implicit in Tester’s quote, that we must examine mediation as the most important ethical power of contemporary public life. Ethics has to do with the norms according to which television represents the spectators’ relationship to the distant ‘other’, to somebody the spectator does not experientially or culturally identify with and cannot, in principle, share the misfortune of. How does this difference between spectators and sufferers become meaningful on television? Can distant ‘others’ be endowed with humanness or will they always remain radical and irrevocable alterities?

Such questions are never purely ethical. They are also political. The mediation between spectator and sufferer is a crucial political space because the relationship between the two of them maps on to distinct geopolitical territories that reflect the global distribution of power. As Cohen rightly notes, it is always ‘audiences in North America or Western Europe [that] react to knowledge of atrocities in East Timor, Uganda or Guatemala’, rather than the other way round.7

What happens when the roles are reversed and the West suddenly becomes the sufferer, as in the September 11th attacks? What happens, in other words, when a shift occurs from a hypothetical thinking of the USA as a sufferer to thinking that the suffering of the superpower is now a historical fact? The shock of those attacks, Chomsky (2001) reminds us, lies ‘not in their scale and character but in the target’. Indeed, rapid changes in the management of the world order after September 11th show only too clearly that any attempt to shift the dominant sufferer–spectator position belongs to the political as much as the ethical order.

It is this close articulation of ethics with politics in the mediation of suffering that raises the question of public action. What kind of public demands do sufferers make on spectators, if at all? Are spectators supposed to forget about the suffering or stand up and take sides? At this point, we can clearly see the equivalence that the theme of intimacy at a distance establishes between the celebrity and the sufferer. Both figures, the celebrity and the sufferer, enable us to examine mediation as the public space that reorganizes relationships in the private space. However, in suffering, intimacy takes on a different nuance. The sentiment of pity, which the sufferer may evoke, raises questions of political power and cultural difference. In so doing, it organizes the disposition of the spectator not (at least not only) around the identity of the cultural consumer or the celebrity fan, but mainly around the public figure of the citizen of the world, the cosmopolitan.

What we need to examine, then, is the conditions of possibility under which the figure of the cosmopolitan may come into being in the process of mediation. In what follows, I examine the degree to which social theory on media and mediation conceptualizes the cosmopolitan spectator as a public actor. I do so in two moves. In the next section under the heading ‘Mediation and Cosmopolitanism’, I discuss the two key narratives on the ethics of mediation – pessimistic and optimistic. I argue that neither leaves conceptual space for the question of how the spectator’s connectivity to the distant ‘other’ is symbolically achieved. The idea of cosmopolitanism may be inseparably connected to the media, yet much theory on the media takes the idea of cosmopolitanism for granted.

In the section after this, ‘The public realm and cosmopolitanism’, I evaluate the two models of the public realm that the debate on mediation presupposes – the dialogue and dissemination models (Peters, 1999). I argue that, for different reasons, each of these models of the public realm fails to conceptualize it as a space where dispositions to action at a distance may be effectively forged. Again, current transformations in public life are seen as connected to the media, yet much theory on the media takes the idea of public life for granted.

If the conditions for cosmopolitanism and the public realm are not objects of investigation, what, is then, the main object of theory on the media? The main object, I claim, is technology. Once more, however, the two most pressing ambivalences that technology h...