- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introducing Social Networks

About this book

This first-rate introduction to the study of social networks combines a hands-on manual with an up-to-date review of the latest research and techniques.

The authors provide a thorough grounding in the application of the methods of social network analysis. They offer an understanding of the theory of social structures in which social network analysis is grounded, a summary of the concepts needed for dealing with more advanced techniques, and guides for using the primary computer software packages for social network analysis.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS AND NETWORKS

It is not unusual to see a wry smile and hear the quip that structural analysts see networks absolutely everywhere. Social structures are indeed networked. But any idea backfires beyond a certain point. The first issue is to inject real content into a concept that is expected to describe and explain a wide spectrum of social phenomena including kinship, power, communication, exchanges, economic markets, organizations, rural and urban communities, sociability and social support. In order to preserve a tight focus, we should begin by staking out our territory. That is far from obvious.

We shall start this chapter with Milgram’s experiment, which shows that social relations are transitive, but in ways that generate different and complex answers to a simple question like ‘How many people do you know?’ The problem comes from the fact that a social network has no natural frontiers. Methodologically, we must therefore begin by deciding where to draw the boundaries that will yield network data of the highest grade. As we shall see, there are two main schools. One operates with personal networks, and the other with total networks. The latter school is more pertinent to the structural subjects of this book, but we dare not disregard the former, one of the linchpins of relational sociology.

The Small World Problem

Everyone has probably already met a stranger, only to discover one or more mutual acquaintances and sigh ‘Gee, what a small world!’ Some sociologists have gone on to wonder how this actually works out in the field. The first studies date back to the 1960s and we now know a good deal about the small world problem. We shall briefly sketch out the formal aspects (Kochen, 1989) and proceed directly to a few empirical results.

There are several strategies with which to tackle the problem of chance encounter. One angle is to start by asking: ‘To what degree does every member of a given group know every other member?’ It is conceivable that, although every member will not have met every other directly, they are nonetheless all linked to one another by chains of acquaintanceship with varying numbers of intermediaries. The average number of intermediaries between two people indicates the degree to which everyone knows everyone else. Person-to-person chains (see Chapter 3) must exist that will eventually link up absolutely any two individuals, except of course for members of totally isolated groups who know zero non-members. If a and z are any two individuals, a chain of intermediaries exists somewhere out there such that we obtain a–b–c . . . x–y–z. This reformulates the small world problem to read: given two individuals chosen at random in any population, what is the probability that 0, 1, 2 or k is the minimum number of intermediaries required to connect them?

In order to collect empirical data for an answer to that question on the scale of societies like France or the United States, we need a tool of investigation. Stanley Milgram was one of the first to design and apply this sort of interviewing tool in the field and his works have become classics (Milgram, 1967). We shall describe the results from a study he conducted with Jeffrey Travers (Travers and Milgram, 1969). They sum up their procedure as follows:

An arbitrary ‘target person’ and a group of ‘starting persons’ were selected, and an attempt was made to generate an acquaintance chain from each starter to the target. Each starter was provided with a document and asked to begin moving it by mail toward the target. The document described the study, named the target, and asked the recipient to become a participant by sending the document on. It was stipulated that the document could be sent only to a first-name acquaintance of the sender. The sender was urged to choose the recipient in such a way as to advance the progress of the document toward the target; several items of information about the target were provided to guide each new sender in his choice of recipient. Thus, each document made its way along a chain of acquaintances of indefinite length, a chain which would end only when it reached the target or when someone along the way declined to participate. Certain basic information, such as age, sex and occupation, was collected for each participant.

Documents operated just like biological markers.

All starters were told the target was a stockbroker living in Boston. They were divided into the following three populations:

(a) | a random sample of Boston residents (n = 100) |

(b) | a random sample from all Nebraska residents (n = 96) |

(c) | a sample of share-owning Nebraska residents (n = 100). |

The three samples were designed to reveal whether living nearer the target or having some business connection to him affected the number of intermediaries needed to reach him. In addition to the token document, each starter received a set of instructions that included, for example:

If you know the target person on a personal basis, mail this folder directly to him. Do this only if you have previously met the target person and know each other on a first name basis. If you do not know the target person on a personal basis, do not try to contact him directly. Instead, mail this folder to a personal acquaintance who is more likely than you to know the target person. You may send the booklet on to a friend, relative or acquaintance, but it must be someone you know personally.

To prevent a document from looping back to someone who had already seen and relayed it, a roster was attached for signature by each sender. Thus all senders had a list of everyone who had already handled the packet. The last attachment was a questionnaire about the sender and his or her relations.

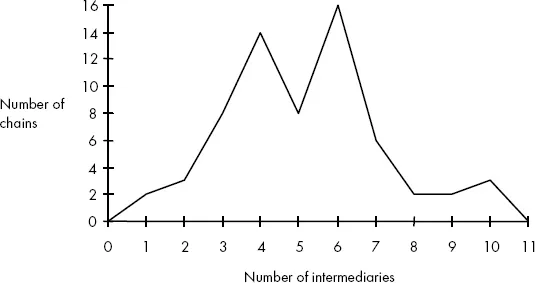

Figure 1.1 Length of completed communication chains (Travers and Milgram, 1969)

Of the 296 persons in the three starting samples, 217 actually moved their documents. The target eventually received 64. The rest were classified as ‘incomplete chains’ because they were mislaid or forgotten along the way. Milgram and Travers point out that the proportion of incomplete chains diminished with the number of intermediaries. In other words, the chances of putting through the document increased with the number of intermediaries. Rosters must therefore have been a motivating factor. Nonetheless, not all relations proved transitive.

Among those that were transitive, 86% of participants sent the document to friends or acquaintances and 14% to kin. The distribution curve in Figure 1.1 shows the lengths of the 64 ‘complete’ chains that reached the target. Chain length is the number of intermediaries needed to connect a starter in a random sample to the target. The mean in this study was 5.2. With due regard for the dangers of generalizing, the Milgram and Travers study demonstrates it only takes an average of five people to connect any two people in a country of over 250 million inhabitants.

This same graph also shows that chain length distribution is bimodal. The Mann–Whitney test confirms a significant difference between the two peaks flanking the trough near the median. Further investigation revealed they reflect two types of complete chains. Complete chains that reached the target person by exploiting knowledge of his address averaged 6.1 intermediaries, while chains exploiting knowledge of the target’s job averaged only 4.6. This explains the bimodal distribution. Documents which exploited address to reach the target reached Boston quickly, but floundered for some time before final arrival. On the other hand, documents routed with the help of job knowledge reached the target’s employer more quickly and contact followed immediately thereafter. Nonetheless, complete chains with random starters in Boston often proved shorter than similar chains out of Nebraska and the difference is significant (4.4 versus 5.7 intermediaries respectively).

The chains show overlap as they converge on the target. In other words, some intermediaries appear in several chains and this phenomenon increases the closer one comes to the target. The 64 copies of the packet were finally handed to him by only 26 people. The target received 16 documents from one neighbour alone, 10 from the same work colleague and five from a second colleague (the rest were scattered among the 23 other individuals). In the end, these three penultimate intermediaries accounted for 48% of completed chains. This convergence in communication chains on certain people is an important feature of small world networks.

Milgram’s experiment made a breakthrough in the small world problem when he established that the average distance between two individuals was about five people in a mass society. Later studies (Kochen, 1989) confirm that this value is relatively stable, even with substantial variations in starter selection criteria. So it is important to remember the figure and to know it is stable.

Computer simulations on a planetary model claim that ‘no more than 10 or 12 links are required to go from any person to any other person via the relationship “knows”, where “knows” is defined as can recognize and be recognized by face and name’ (Rapoport and Yuan, 1989). Small world research has a wide range of applications including epidemiology and biased samples in statistics.

How Many People Do You Know?

We have just discussed chains of acquaintances as if the definition were self-evident. But what exactly does it mean to know someone? We ‘know’ a state governor or a film star because we have a name and lots of information about her. With that definition, anybody can list huge numbers of people she ‘knows’ but yield no faithful picture of her network. So ‘know’ needs to mean ‘know personally’. But we need an even more restrictive definition if we are to design useful studies and obtain intelligible results.

Granovetter (1976) was the first of many authors to insist that the question ‘how many people do you know?’ as such has little sociological meaning. Questions become meaningful in a study only if they yield results whose quality can be evaluated, i.e. the questions conform to an interview methodology and to a reliable sampling process. In short, the question ‘how many people do you know?’ becomes meaningless if detached from the method used to obtain a list of names from respondents. But the first issue is the exact meaning of ‘how many people have you personally met or established direct contact with?’

Ithiel de Sola Pool (1978) once ran a little personal experiment. Every da...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION: THE PARADIGM OF STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

- 1 SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS AND NETWORKS

- 2 PERSONAL NETWORKS AND LOCAL CIRCLES

- 3 GRAPH THEORY

- 4 EQUIVALENCE AND COHESION

- 5 SOCIAL CAPITAL

- 6 POWER AND CENTRALITY

- 7 DYNAMICS

- 8 MULTIPLE AFFILIATIONS

- APPENDIX

- Bibliography

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introducing Social Networks by Alain Degenne,Michel Forsé in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.