eBook - ePub

The Risk Society and Beyond

Critical Issues for Social Theory

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Risk Society and Beyond

Critical Issues for Social Theory

About this book

Ulrich Beck?s best selling Risk Society established risk on the sociological agenda. It brought together a wide range of issues centering on environmental, health and personal risk, provided a rallying ground for researchers and activists in a variety of social movements and acted as a reference point for state and local policies in risk management. The Risk Society and Beyond charts the progress of Beck?s ideas and traces their evolution. It demonstrates why the issues raised by Beck reverberate widely throughout social theory and covers the new risks that Beck did not foresee, associated with the emergence of new technologies, genetic and cybernetic. The book is unique because it offers both an introduction to the main arguments in Risk Society and develops a range of critical discussions of aspects of this and other works of Beck.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Risk Society and Beyond by Barbara Adam, Ulrich Beck, Joost Van Loon, Barbara Adam,Ulrich Beck,Joost Van Loon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

RECASTING RISK CULTURE

1

Risk Society or Angst Society? Two Views of Risk, Consciousness and Community

Alan Scott

Every technology produces, provokes, programs a specific accident … The invention of the boat was the invention of shipwrecks. The invention of the steam engine and the locomotive was the invention of derailments. The invention of the highway was the invention of three hundred cars colliding in five minutes. The invention of the airplane was the invention of the plane crash. I believe that from now on, if we wish to continue with technology (and I don’t think there will be a Neolithic regression), we must think about both the substance and the accident. …

(Paul Virilio, 1983: 32)

Wir [Deutschen] sind Weltmeister der Angst.

(Helmut Schmidt speech, 15 May 1996)

Since the first publication of Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society, the intervening years have provided enough reminders, as if reminders were needed, of the centrality of risk in contemporary societies. There have been spectacular accidents, Chernobyl being the most spectacular. AIDS has initiated intense discussion of risk and personal sexual expression. Anxiety about deforestation due to acid rain or economic exploitation, holes in the ozone layer and other slow-burning issues have become a permanent background feature of normal politics occasionally pushing themselves into the foreground, sometimes through nothing more extraordinary than the arrival of summer. First glasnost, then the collapse of the Soviet Union have revealed previously hidden environmental damage on an enormous scale. Third World populations remain no less, and are arguably more, vulnerable to natural and social catastrophes. In the still affluent West growing unemployment and declining security, even for those in employment, not least due to the decline in welfare facilities, have heightened awareness of vulnerability to contingencies such as ill health, accident and old age.

It is in this context that Risk Society and Beck’s subsequent work represents one of two systematic attempts by social scientists to wrest the issue of risk away from specialists (the risk analysts) and place it on a wider social scientific and public agenda. The work of Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky is the other (see Douglas and Wildavsky, 1983; Douglas, 1992). Although they have this common purpose, there are striking differences between the two approaches and their implication for assessing the objective ‘risk of risk’ are quite distinct. Since Beck’s work stands at the centre of this volume, the aim of this discussion will be to examine his analysis, in part, in the light of its major ‘rival’ perspective.

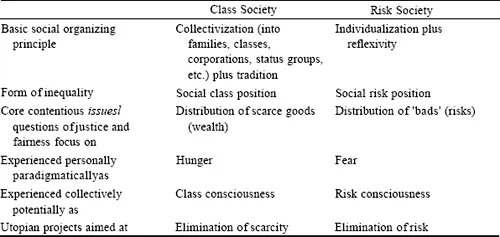

There is a striking combination of the familiar and the novel in Risk Society which might be caught in the observation that the work makes an unconventional claim in a conventional guise. Since it is the novel content rather than the conventional form which has - unsurprisingly and rightly - received most attention, I would like to focus here on the latter; on the argumentative and rhetorical structure which is the medium of the argument. This structure may be considered conventional in that it assumes the shape of a narrative of discontinuity of a type familiar in sociological argument. Industrial versus post-industrial (or information) society, modernity versus post- or late modernity, fordism versus post fordism, nation state societies versus global networks; all these oppositions and the claims which accompany them are grist to the mill of sociological debate. The particular opposition which underpins Beck’s analysis is that between a class society and a risk society, and underlying this distinction in tum is the more crucial dualism of scarcity versus insecurity (risk) through which the organizing principles and the core contentious issues of these two social forms may be identified. Since much of Beck’s analysis and many of his observations, particularly in the early chapters, echo this dualistic argumentative strategy, they can be economically represented in Table 1.1.

Any critical response to this analysis would have to do more than merely show that neither of these two societies exists in pure form. Beck is well aware and keen to emphasize that, for example, issues of scarcity and of the distribution of goods are not absent within the contemporary risk society. Nor would it be sufficient to demonstrate that Beck is basing a general diagnosis of modernity on a specifically German (or even Bavarian) experience (though one does sometimes feel that ‘Germany’ and ‘advanced contemporary society’ are treated as synonyms). Although this raises problems, to which we shall return below, there is a sense in which this generalization from a specific case is neither here nor there. Much classical sociological theory is prompted by quite specific contexts or events, the key question being whether the formulation of the reflections stimulated by such events finds echoes in (and is thus generalizable to) other places and later times. Thus, while I think it might be reasonable to suggest that the primary immediate contextual background of Risk Society was the campaign against a planned nuclear reprocessing plant in Bavaria (Wackersdorf), this is a no less legitimate starting point for theoretical reflection than the Dreyfus affair was for Durkheim’s reflections on individualism, or Prussian bureaucracy and Bismarck’s social policy for Weber’s theory of bureaucratic domination.

TABLE 1.1 Class society versus risk society

So, rather than criticize Beck for ignoring the ‘good old problems’ of the class society or for the possible ‘Bavariacentrism’ of his vision, the crucial question is whether the claim that ‘scarcity’ and ‘risk’ are qualitatively distinct holds water. It is upon this assumption that the validity of the distinction between class and risk society ultimately rests.

One source of doubt about the distinction is raised by the simple question: is insecurity not merely the flip side of scarcity? Or, more strongly, is insecurity not a function of scarcity? In the German folk poems collected in the early nineteenth century under the generic title Des Knaben Wunderhorn (and still widely known through Mahler’s settings) there is a pair of thematically linked poems called ‘Earthly Life’ and ‘Heavenly Life’ which illustrate the problem vividly. ‘Earthly Life’ is a tale of a child’s hunger-induced death angst and of the mother’s attempt to calm the child’s fear while simultaneously disguising her own. Predictably, the child is lying on the death bier before the promised bread has arrived on the table. In contrast, in the folk vision of heaven, heaven is represented not merely by abundance, but also by release from toil and from the money economy (‘the wine cost not one penny’). In ‘Earthly Life’ it is insecurity - in this case due to the unpredictability and slowness of supply - rather than absolute scarcity upon which fear is fixed: the crop had ripened, the harvest had been gathered, the corn threshed. In fact the poems are dotted with examples of fear induced by insecurity and, significantly, these fears are not always focused upon hunger; war and consequences of war are no less common cause of anxiety. Hunger here is not, even paradigmatically, the typical source offear, but is merely one of many misfortunes which can befall those in insecure positions; insecurity being the inability to control those events which impact directly upon life chance. To define insecurity in these terms - i.e. in terms of environmental unpredictability rather than objective risk - is to suggest that while its sources are variable (both within and between societies) there is a necessary link to scarce resources, be they basic needs such as food and shelter, or a secure position within the ‘nonnal employment relation’. ‘I am afraid’, for Beck the motto of the risk society, is no less appropriate to class societies even if the focal point of anxiety has shifted. Fear of hunger, like the risk of ecological catastrophe, is most of the time probabilistic.

But there is a further move in the Risk Society which may have been intended to pre-empt this objection. Beck argues that modern risks are qualitatively different from earlier scarcity because the visible, tangible and localized nature of wealth can insulate the wealthy from the misfortunes of the poor, while even those in relatively advantageous ‘social risk positions’ cannot be insulated from the intangible and deterritorialized (globalized) nature of contemporary risks such as pollution and general environmental deterioration. All this Beck neatly captures in the fonnulation ‘poverty is hierarchic, smog is democratic’ (1992: 36). But such a move does not of itself address doubts about the water-tightness of the scarcity/insecurity divide for two related reasons. First, particularly in agrarian societies (but to a degree in industrial societies also) the wealthy were only ever relatively insulated from the catastrophes which befell the poor. Wealth affects the level of exposure to the risk of, say, harvest failure and famine, and could certainly dampen the effects of such catastrophes, but there was rarely a completely secure position. Secondly and conversely, wealth can and does offer (relative) protection from contemporary risks. Those who can, do move away from areas of high pollution, environmental degradation and danger. That this does not offer ultimate security from environmental disaster does not thereby place them in a significantly different position from those with relative wealth in ‘scarcity societies’. The crucial point here is that the assertion of a qualitative difference between scarcity and risk is only plausible if ultimate catastrophe (the ‘greatest theoretically possible accident’) is taken as the paradigmatic form of contemporary risk; i.e. if we neglect degrees of risk by subsuming all risk categories under the umbrella of total catastrophe (under the nuclear mushroom, as it were). But, as Beck is aware, the‘greatest theoretically possible accident’ upon which the fears of social movement activists are, understandably, focused is a hypothetical construct. It is not, however, the form that risk takes when actors are making routine daily decisions as to where and how to live. Despite an awareness of gradations of risk, there is a slippage in the analysis in which at key points the actually existing risks - as opposed to hypothetical risk - are subsumed under ultimate catastrophe.l But it is no more legitimate to take maximum catastrophe as archetypal of modern risk than to take absolute harvest failure as being the archetype of scarcity. In both cases the empirical reality facing actors as they make decisions at any given point is (most of the time) sub-catastrophic, relative, and to a degree predictable. This means that in effect the wealthy were protected from scarcity and remain protected from risk; ‘protection’ here being understood as ‘relative protection’. Smog is just as hierarchical as poverty so long as some places are less smoggy than others.2

Doubt about the validity of the distinction between scarcity and risk raises further, and more fundamental, doubts about the two characteristics Beck imputes to the risk society: individualization and reflexivity. One of the key arguments in Risk Society takes up the German debate about the decline in the so-called Normalarbeitsverhiiltnis (standard employment relation) - i.e. the secure, largely male employment patterns upon which not merely the distribution of labour (both within the labour market and the domestic division of labour) but also much of Germany’s political and welfare system rests.3 Beck’s argument, briefly expressed, is that the shift towards less secure, more ‘flexible’ patterns of employment has undermined deeply-held assumptions about both employment-based status groupings (Germany’s almost stiindisch - estate status consciousness) and the gender division of labour in the ‘public’ and ‘private’ spheres. As Mark Ritter, Risk Society’s translator, indicates (Beck, 1992: 129), the term Beck uses to describe the implication of this process, Freisetzung, is exquisitely (and intentionally) ambiguous in that it means both liberation (‘setting free’) and dismissal/redundancy. For Beck - as for his later British-based co-authors - this liberation ‘detraditionalizes’ values and the social relations they embody. The ultimate implication of this ‘individualization of risk’ (see Beck et al., 1994: 100) is that ‘the individual himself or herself becomes the reproduction unit of the social in the lifeworld’ (ibid.: 90). Status groups, corporate entities and families lose their function in reproducing not merely culture within the lifeworld, but also, to a degree, social privilege. For the individual this floating free from (or being thrown out of) both security and tradition means being faced with choices in place of established paths with their supporting norms and expectations. We are forced to reflect where reflection was previously not required (‘forced to be free’). Such reflection seeps deep into the most private recesses of our lives on a routine daily basis; into our every action as colleagues, parents, partners, children. Insecurity is thus not merely an environmental context, it is an existential state; echoing Wittgenstein, we no longer ‘know how to go on’ on the basis of sacred tradition. Here we are close to Habermas’ analysis of the destruction of tradition through the increasing reach of instrumental rationality and ‘systems’ logic’ (Habermas, 1987). For Beck, as for Habermas, this process means that taken-for-granted values and assumptions become, to use Habermas’ term, ‘virtualized’, i.e. their previously implicit validity claims become thematized, problematic and thus potentially called into question and to account. ‘Reflexive modernization’ is the catch phrase through which Beck seeks to capture these complex processes.4

Although perhaps vulnerable to the accusation of exaggeration (particularly in the German case), there is much in this analysis of Freisetzung which is both plausible and powerful. Where the analysis becomes problematic is in the use to which it is put to support what I earlier called a ‘narrative of discontinuity’, i.e. to support the claim that there is some new break between a modernity which is and one which was not (or was less) ‘reflexive’. The point can be made with reference to Georg Simmel to whom the credit for the term ‘individualization’ may be ascribed.

Central to Simmel’s analysis is the argument that individualization is not a once-and-for-all ‘event‘; rather it occurs each time, say, an informal social relation is replaced by a monetary one. Thus, not only does individualization occur much earlier in modernity (or even pre-modernity) than can be imagined within the narrow historical vision of debates about contemporary social change but, more importantly, for Simmel, the push towards individualization is a constant feature of modem social forms, and one which furthermore is in ceaseless tension with tradition.5 The idea that one can use the concept of ‘individualization’ as a tool for periodizing modernity is thus foreign to Simmel. The thought which animated his use of the notion is much closer to that which lay behind Marx’s observation that the capitalist means of production are, and must be, constantly revolutionizing (though Simmel extends this insight beyond the confines of capitalism and the economic sphere). It resembles too Karl Polanyi’s argument that markets become ‘disembedded’ from traditional relations (Polanyi, 1957) and Weber’s claim that each ‘modernizing offensive’ (the term is Peter Wagner’s, 1994) is accompanied by a ‘bureaucratic revolution’ in which traditional patterns are systematically and consciously destroyed (Weber, 1968).6 Where these accounts differ from the use Beck has made of the concepts of ‘individualization’ and ‘reflexivity’ is that the processes they describe are (to varying degrees) independent of anyone narrow historical time frame. This is particularly clear in Simmel where individualized forms constitute one always available type of sociation (albeit one which is loosely associated with ‘modern’ relations based upon monetary exchange, labour contracts, etc.).

The point here is not that Beck has misunderstood or misused Simmel’s concept of individualization, but rather that Simmel’s account, though less tidy, is more plausible. Beck’s argument, like Habermas’, is in the line of strongly discontinuous narratives of modernity whereas - above all - Simmel and Polanyi, posit a complex and permanent struggle between those which we call ‘modem’ and those which we call ‘traditional’ ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Repositioning Risk; the Challenge for Social Theory Barbara Adam and Joost van Loon

- PART I Recasting Risk Culture

- 2 Risk Culture Scott Lash

- 3 Risk, Trust and Scepticism in the Age of the New Genetics Hilary Rose

- PART II Challenging Big Science

- 5 Genotechnology: Three Challenges to Risk Legitimation Lindsay Prior, Peter Glasner and Ruth McNally

- 6 Health and Responsibility: From Social Change to Technological Change and Vice Versa Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim

- PART III Mediating Technologies of Risk

- 8 Liturgies of Fear: Biotechnology and Culture Howard Caygill

- 9 Virtual Risks in an Age of Cybernetic Reproduction Joost van Loon

- PART IV P(l)aying for Futures

- 11 Discourses of Risk and Utopia Ruth Levitas

- 12 Risk Society Revisited: Theory, Politics and Research Programmes Ulrich Beck

- Index