- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

"An outstanding entry level text aimed at those with little or no cultural studies knowledge... Innovative, creative and clever."

- Times Higher Education

"The ideal textbook for FE and first year HE cultural studies students. Its quality and character allow the reader to 'feel' the enthusiasm of its author which in turn becomes infectious, instilling in the reader a genuine sense of ebullient perturbation."

- Art/Design/Media, The Higher Education Authority

An introduction to the practice of cultural studies, this book is ideal for undergraduate courses. Full of practical exercises that will get students thinking and writing about the issues they encounter, this book offers its readers the conceptual tools to practice cultural analysis for themselves. There are heuristics to help students prepare and write projects, and the book provides plenty of examples to help students develop their own ideas.

Written in a creative, playful and witty style, this book:

- Links key concepts to the key theorists of cultural studies.

- Includes a wide range of references of popular cultural forms.

- Emphasizes the multidisciplinary nature of cultural studies.

- Includes pedagogical features, such as dialogues, graphs, images and recommended readings.

- The book?s skills-based approach enables students to develop their creative skills, and shows students how to improve their powers of analysis generally.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

High Cultural Gladiators: Some Influential Early Models of Cultural Analysis

Culture and Anarchy in the UK: a dialogue with Matthew Arnold | 1 |

Introduction

- To understand how Arnold understood and defined culture and why he felt contemporaries were in need of his model of culture.

- To appreciate how Arnold’s definition grew out of his reactions to the historical circumstances in which he lived.

- To see how his ideas relate to class and politics.

- To consider Arnold’s ideas in a critical but informed way and recognize how these ideas are related to important methodological concerns within cultural studies.

Matthew Arnold and the culture and civilization tradition

Culture: what it is, what it can do

DIVAD NOTLAW: | Now Mr Arnold, in your lifetime you were known as a poet, a social and literary critic, a professor of poetry (at Oxford University), and a schools’ inspector. You constantly reflected on the meaning and effects of culture throughout your life and it is this that has left its mark on what we now call cultural studies. Your book Culture and Anarchy (1869) has had quite an influence on discussions about cultural value. Now, given that I’m interested in how to do cultural analysis, could you comment on what you were doing in this book? |

ARNOLD: | I ought to say, to begin with, that I never reflected directly on method but I’ll do my best to answer your question. What I proposed was to enquire into what ‘culture really is’, what good it can do, and why we need it. I also tried to establish ‘some plain grounds on which a faith in culture – both my own faith in it and the faith of others – may rest securely’ (Arnold [1869] 1970: 203). |

NOTLAW: | So, in the first place, you were interested in defining culture. OK, so in your view, what is culture? |

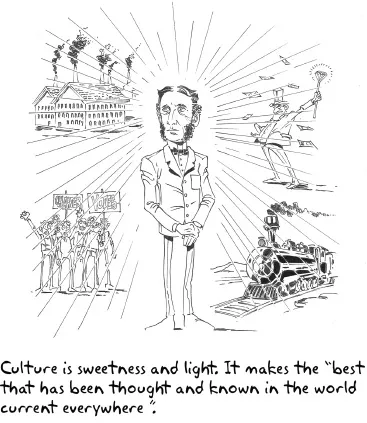

ARNOLD: | Well, to answer this you might look at the title of my first chapter which is called ‘Sweetness and Light’. Firstly, culture can be related to curiosity which is a question of looking at things in a disinterested way and ‘for the pleasure of seeing them as they really are’ (204–5). But this is only a part of an adequate definition because curiosity has to be linked to a study of perfection. Well (here Arnold hesitates), culture, properly described, doesn’t really have its origin in curiosity but in the love of perfection: ‘it is a study of perfection. It moves by the force […] of the moral and social passion for doing good’ (205). |

NOTLAW: | (politely but a little perplexed) So, you start by saying that it’s concerned with curiosity and then that it’s the study of perfection. Why contradict yourself? |

ARNOLD: | It’s simply part of the way I think. Now, before any of you high-powered cultural theorists get hold of me, I ought to emphasize that I saw my approach as simple and unsystematic. |

NOTLAW: | OK, let’s try to live with that. When you say that culture as the study of perfection is motivated by ‘the moral and social passion for doing good’, you seem to be arguing that culture serves a very important ethical purpose. If we think about this in terms of method, the definition of culture can’t be divorced from bringing about positive change. |

ARNOLD: | That’s true; culture realizes a Christian purpose. I believed that culture ‘believes in making reason and the will of God prevail’ (206). |

NOTLAW | (not wanting to offend and thinking, ‘Well, he doesn’t say much about what reason is or how we can know what God’s will is’): Hmm, well, let’s move the argument on a little. We know that, in an unsystematic way, you see culture as seeing things as they really are, the study of perfection linked to curiosity, reason and God’s will, but let’s move on to your next stated aim, what good Culture can do. |

ARNOLD: | My simple answer is that it can help us achieve ever higher states of inner perfection. It is in ‘endless growth in wisdom and beauty’, that is how ‘the spirit of the human race finds its ideal’. It is here we find that culture is ‘an indispensable aid’, this is the ‘true value’ of culture: it’s not ‘a having and a resting, but a growing and a becoming, [this] is the character of perfection as culture conceives it; and here, too, it coincides with religion’ (208). Yet culture goes beyond religion. |

NOTLAW: | I’d like to stop you there and say that although I don’t agree with everything you say I like the idea of culture as a question of growing and becoming: this suggests that it doesn’t have a fixed identity – it is never static. |

ARNOLD: | But you conveniently forget that I connect it to the question of inner perfection. To help you sum up my argument I would add that culture is: ‘a harmonious expansion of all the powers which make the beauty and worth of humanity’ (208); it chooses the best of everything and helps to preserve it; it helps us to judge correctly (236) and to discover our best self (246) through reading, observing, and thinking (236). In short, culture is a humanizing of knowledge and the pursuit of perfection is an internal condition rather than a development of external things or ‘animality’ (227). |

NOTLAW: | I would say that here it is necessary to see what you are saying with relation to the historical circumstances of the 1860s. You were attacking what you saw as the exaggerated belief ... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: A few preliminary notes to the reader (or, why read this book?)

- Part One: High Culture Gladiators: Some Influential Early Models of Cultural Analysis

- Part Two: The Transformative Power of Working-class Culture

- Part Three: Consolidating Cultural Studies: Subcultures, the Popular, Ideology and Hegemony

- Part Four: Probing the Margins, Remembering the Forgotten: Representation, Subordination and Identity

- Part Five: Honing your Skills, Conclusions and ‘Begin-endings’

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app