Paradigm In general terms a paradigm can be understood as a field or domain of knowledge that embraces a specific vocabulary and set of practices. In the philosophy of science the concept of a paradigm is associated with the writing of Thomas Kuhn, for whom a paradigm is a widely recognized field of understanding or achievement in science that provides model problems and solutions to the community of practitioners. Here a paradigm lays down the guiding principles and conceptual achievements of a working model that attracts adherents and enables ‘normal science’ to proceed.

Kuhn argues that science periodically overthrows its own paradigms so that a period of stable ‘normal science’ is commonly preceded by the overthrow of the existing paradigmatic wisdom. This revolutionary process is known as a paradigm shift. An example would be the substitution of Copernican science by a Newtonian paradigm or the subsequent displacement of classical physics by quantum mechanics. Having said this, the concept of a paradigm may also be deployed in the context of the humanities and social sciences where various ‘perspectives’ (functionalism, symbolic interactionism, structuralism, poststructuralism etc.) might be grasped as paradigms. Thus, Stuart Hall describes culturalism and structuralism as key paradigms in the development of cultural studies.

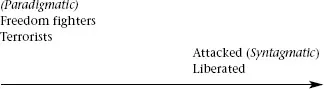

The idea of the paradigmatic also forms a part of semiotics in that, for Saussure, meaning is produced through the selection and combination of signs along the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes. The syntagmatic axis is constituted by the linear combination of signs that form sentences while paradigmatic refers to the field of signs (i.e., synonyms) from which any given sign is selected. Meaning is accumulated along the syntagmatic axis, while selection from the paradigmatic field alters meaning at any given point in the sentence. For example, in Figure 2 on the paradigmatic axis, the selection of freedom fighter or terrorist is of meaningful significance. It alters what we understand the character of the participants to be. Further it will influence the combination along the syntagmatic axis, since it is by convention unlikely, though grammatically acceptable, to combine terrorist with liberated.

Figure 2

Links Cultural studies, episteme, epistemology, semiotics, truth

Patriarchy The idea of patriarchy refers to a social order in which there is recurrent and systematic domination of men over subordinated women across a wide range of social institutions and practices. The term, which is connected to feminist theory and gained currency during the second wave of the women’s movement dating from the 1960s, clearly carries the connotations of the male-headed family, mastery and superiority. As such, the concept of patriarchy asserts that sex is a central organizing principle of social life where gender relations are thoroughly saturated with power.

Many feminists have argued that contemporary sexed subjectivities are not universals but rather the consequence of the relations between men and women that are formed in the context of patriarchal family arrangements which, if challenged, could be changed. From a psychoanalytic point of view, patriarchy provides the context in which through identification with the father and symbolic Phallus as the domain of social status, power and independence boys take on a form of externally oriented masculinity achieved at the price of emotional dependence on women. In contrast, while girls acquire a greater surety with the communicative skills of intimacy through introjection of, and identification with, aspects of their mothers’ own narratives, they have greater difficulty with externally oriented autonomy.

A criticism of the concept of patriarchy is its treatment of the category of woman as an undifferentiated one. That is, all women are taken to share something fundamental in common in contrast to all men. Thus it can be argued that the concept obscures the differences between individual women and their particularities in favour of an all-embracing universal form of oppression. Not only do all women appear to be oppressed in the same way but also there is a tendency to represent them as helpless and powerless. This stress on difference is shared by feminists influenced by poststructuralism and postmodernism whose anti-essentialist stance suggests that femininity and masculinity are not essential universal categories of either biology or culture but discursive constructions.

Links Anti-essentialism, feminism, gender, identification, psychoanalysis, subjectivity, women’s movement

Performativity A ‘performative’ is a linguistic statement that puts into effect (brings into being) the relation that it names, for example, within a marriage ceremony ‘I pronounce you …’ is a performative statement. Similarly, performativity is a discursive practice that enacts or produces that which it names through citation and reiteration of the norms or conventions of the ‘law’. Thus, the discursive production of identities through repetition and recitation of regulated ways of speaking about identity categories (for example, masculinity).

Performativity is not a singular act but rather is always a citation and reiteration of a set of existent norms and conventions. For example, judges in criminal and civil law do not originate the law or its authority but cite the conventions of the law that is consulted and invoked. This is an appeal to an authority that has no origin or universal foundations. Indeed, the very practice of citation produces the authority that is cited and reconstitutes the law. The maintenance of the law is a matter of re-working a set of already operative conventions and involves iterability, repetition and citationality.

Though Austin originated the idea of a performative in 1962, it was Judith Butler who popularized the concept of performativity within cultural studies during the 1990s. In particular, Butler conceives of sex and gender in terms of citational performativity. For Butler, ‘sex’ is produced as a reiteration of hegemonic norms, a performativity that is always derivative. The ‘assumption’ of sex, which is not a singular act or event but an iterable practice, is secured through being repeatedly performed. Thus gender is performative in the sense that it constitutes as an effect the very subject it appears to express.

Butler combines this reworking of discourse and speech act theory with psychoanalysis to argue that the ‘assumption’ (taking on) of sex involves identification with the normative phantasm (idealization) of ‘sex’. Sex is a symbolic subject position assumed under threat of punishment (for example, of symbolic castration or abjection). The symbolic is a series of normative injunctions that secure the borders of sex (what shall constitute a sex) through the threat of psychosis and abjection (an exclusion, throwing out or rejection). Butler goes on to argue that drag can destabilize and recast gender norms through a re-signification of the ideals of gender. Through a miming of gender norms, drag can be subversive to the extent that it reflects on the performative character of gender. Drag suggests that all gender is performativity and as such destabilizes the claims of hegemonic heterosexual masculinity as the origin that is imitated. That is, hegemonic heterosexuality is itself an imitative performance which is forced to repeat its own idealizations.

Links Discourse, identification, identity, psychoanalysis, sex, speech act

Phallocentric In a general sense, the concept of phallocentric refers to male-centred discourse or from the perspective of a privileged masculinity. More particularly, the idea has been deployed in reference to the use of the term Phallus within psychoanalytic theory where the Phallus is held to be a symbolic transcendental universal signifier of the source, self-origination and unifying agency of the subject. This is argued to be especially the case in relation to psychoanalysis as developed by Lacan.

For its critics, the phallocentric character of psychoanalysis follows from Freud’s assertion that women would ‘naturally’ see their genitals as inferior in tandem with the claim that genital heterosexual activity that stresses masculine power and feminine passivity is the normal form of sexuality. Further, in Lacan’s reworking of Freud, the Oedipal moment marks the formation of the subject into the Law of the Father, and thus entry into the symbolic order itself. That is, the power of the Phallus is understood to be necessary to the very existence of subjects. For Lacan, the symbolic Phallus:

- Acts as the ‘transcendental signifier’ of the power of the symbolic order.

- Serves to split the subject away from desire for the mother thus enabling subject formation.

- Marks the necessary interruption of the mother–child dyad and the subject’s entry into the symbolic (without which there is only psychosis).

- Allows the subject to experience itself as a unity by covering over a sense of lack.

For critics such as Irigaray, the centrality of the Phallus within Lacan’s argument renders ‘woman’ an adjunct term so that the feminine is always repressed and entry into the symbolic continually tied to the father/Phallus. Indeed, for Irigaray the whole of Western philosophy is phallocentric so that the very idea of ‘woman’ is not an essence per se but rather that which is excluded. Here the feminine is understood to be the unthinkable and the unrepresentable ‘Other’ of phallocentric discourses.

Links Écriture feminine, feminism, Other, psychoanalysis, sex, subjectivity

Place Since the 1980s cultural studies has shown a growing interest in questions of space and place influenced in particular by Foucault and his exploration of the intersections of discourse, space and power. In this context, a place is understood to be a site or location in space constituted and made meaningful by social relations of power and marked by identifications or emotional investments. As such, a place can be understood to be a bounded manifestation of the production of meaning in space.

The organization of human activities and interactions within space, that is, in places, is fundamental to social and cultural life. For example, a ‘home’ is divided into different living spaces – front rooms, kitchens, dining rooms, bedrooms etc. These spaces are used in diverse ways and are the arena for a range of activities with different social meanings. Accordingly, bedrooms are intimate spaces into which we would rarely invite strangers; instead, a front room or parlour is deemed to be the appropriate space for such an encounter.

Space and place are sometimes distinguished in terms of absence–presence. That is, place is marked by face-to-face encounters and space by the relations between absent others. Thus, home is a place where I meet my family with regularity and is the product of physical presence and social rituals, whereas e-mail or letters establish contact between absent persons across space. Significantly then, a place is the focus of human experience, memory, desire and identity (which can themselves be understood as discursive constructions) which are the targets of emotional identification or investment.

The concepts of ‘front’ and ‘back’ regions (derived from the work of Erving Goffman) illustrate a fundamental divergence in social-spatial activity. Front space is constituted by those places in which we put on a public ‘on-stage’ performance and act out stylized, formal and socially acceptable activities. Back regions are those spaces where we are ‘behind the scenes’ and in which we prepare for public performance or relax into less formal modes of behaviour and speech. The social division of space into front and back regions or into the appropriate uses of kitchens, bedrooms and parlours is of course cultural. Thus distinct cultures design homes in different ways, allocating contrasting meanings or modes of appropriate behaviour.

Links Discourse, emotion, identification, meaning, power, space

Political economy Political economy is a domain of study that is concerned with power and the distribution of economic resources. Thus, political economy explores the questions of who owns and controls the institutions of economy, society and culture. Within cultural studies the main interest in political economy has been related to the scope and mechanisms by which corporate ownership and control of the culture industries shape the contours of culture.

For example, the institutions of television have been of interest to cultural studies because of their central place in the communicative practices of modern societies. These concerns have become increasingly acute as public service broadcasting has been seriously challenged by commercial television in the context of a broadcasting landscape dominated by multimedia corporations. In particular, since the mid-1980s media organizations have undergone processes of convergence and synergy that has created multimedia giants such as AOL–Time Warner and Walt Disney as governments have relaxed the regulations restricting cross-media ownership.

These are the global trends in the political economy of television that have underpinned a change in programming strategies and thus a change to the patterns of cultures. Thus, contemporary developments in television organization and funding across our world have placed visual-based advertising and consumerism at the forefront of culture. Television is pivotal to the production and reproduction of a promotional culture focused on the use of visual imagery to create value-added brands or commodity-signs. Thus has the political economy of television helped to shape the contours of contemporary culture.

However, one of the central tenets of cultural studies is its non-reductionism so that culture is understood to have its own specific meanings, rules and practices which are not reducible to another category or level of a social formation. In particular, cultural studies has waged a battle against economic reductionism, that is, the attempt to explain what a cultural text means by reference to its place in the production process. For cultural studies, the processes of political economy do not determine the meanings of texts or their appropriation by audiences. Rather, political economy, social relationships and culture must be understood in terms of their own specific logics and modes of development. Each of these domains are ‘articulated’ or related together in context-specific ways.

This argument has been expressed via the metaphor of the ‘circuit of culture’. Here, meanings embedded at the moments of production may or may not be taken up at the levels of representation or consumption where new meanings are again produced. Indeed, meanings generated at the level of representation and consumption shape production itself through, for example, design and marketing. Accordingly a full analysis of any cultural practice requires the analysis of both ‘economy’ and ‘culture’, including the articulation of the relations between them.

Links Articulation, circuit of culture, cultural materialism, Marxism, reductionism, social formation

Politics Politics is concerned with the numerous manifestations and relations of power that occur at all levels of human interaction. Since cultural studies is a field of study centred on the examination of the relations of culture and power, then it follows that the concept of politics is a core concern. However, politics as understood in the context of cultural studies is not simply a matter of electoral parties and governments but of power as it pervades every plane of social relationships. Power is not simply a coercive and constraining force that subordinates one set of people to another, though it certainly is this, but it also generates and enables social action and relationships. In this sense, power, while certainly constraining, is also enabling. Thus, politics is a central activity in the generation, organization, rep...