![]()

The Sound Films

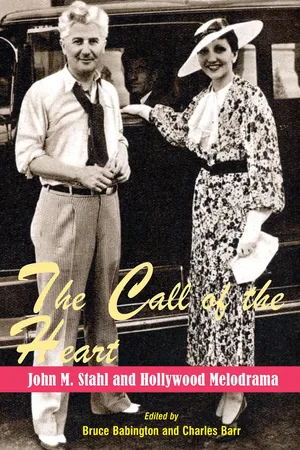

Shooting Magnificent Obsession (1935). Stahl, at left, between the wheels; Irene Dunne in the arms of Robert Taylor.

![]()

Stahl in the Sound Era 1929–1949: Introduction

Bruce Babington

Stahl left Tiffany-Stahl on the cusp of the sound era, entering the second half of his career under contract to Universal, with his first talkie, A Lady Surrenders (1930, aka Blind Wives). In the pages that follow we again present Stahl’s sound films chronologically, tracking his movement to, and activity at, Universal (1930–1939) and Twentieth Century-Fox (1941–1949), with one film at MGM (Parnell, 1937) and one at Columbia (Our Wife, 1940). With his long tenures at Universal (eight films) and at Fox (nine films) the story looks very stable. However, it is, in fact, rather complex.

After resigning from Tiffany-Stahl, and later when he left Universal in 1939, Stahl seriously contemplated pursuing a route apart from the studios as an independent producer-director. As Head of Production at Tiffany-Stahl, a less well-appointed simulacrum of the big studios, he had been unable to direct, and his overseeing duties were so onerous that he produced only one film in the promised category of “special” on which he was able to work closely with director and film. Presumably what he now had in mind, after the chastening Tiffany-Stahl experience of “independence”, was – both in 1929–30 and in 1939–40 – a much smaller and more personalised operation, making perhaps two films a year produced and directed by himself, to be distributed through agreements with the major studios (see Variety, 13 November 1929, 9).

In the immediate post-Tiffany-Stahl period, despite reports of a return to MGM, Stahl’s ambition to “complete plans for the formation of his own producing organization” (Exhibitors World, 14 December 1929) was the dominant story, with Variety reporting, in the story quoted above, that “he has opened offices in the Hollywood Bank Building” to that end. However, Variety, still running the return to MGM story, further reported (24 March 1930, 4) that Stahl’s “plans for independent production did not materialize because of inadequate release channels”, something that would be as true in 1940 as in 1930. The upshot was Stahl’s move to Universal, in what proved to be, under the patronage of Carl Laemmle Jr., as felicitous a decision as his signing with Mayer in 1920 – though both studio connections were to end less happily than they began.

After signing for Universal, Stahl made his earliest sound films: the sophisticated comedy dramas A Lady Surrenders (1930) and Seed (1931), and an adaptation of Preston Sturges’s Broadway comedy hit, Strictly Dishonorable (1931). Following this, he made the five melodramas, Back Street (1932), Only Yesterday (1933), Imitation of Life (1934), Magnificent Obsession (1935) and When Tomorrow Comes (1939). Supported by Carl Laemmle Junior, the head of production until 1936, Stahl enjoyed a golden period, working with great female stars, Irene Dunne (three times), Margaret Sullavan, who made her film debut with Stahl, and Claudette Colbert, and with the male stars John Boles, Robert Taylor, and Charles Boyer. Though Stahl could straddle fences as well as most, the racial problematics of Imitation of Life and the socio-sexual interests of Back Street, as well as the subtly low-keyed style of melodrama he developed, to name the most obvious instances, were genuinely ground-breaking.

The Universal studio files of this time (available in the University of Southern California’s collection) give a great deal of information about Stahl’s working methods at his peak, and the large sums he earned. (In his last years at Universal, because of the contract Laemmle Junior rewarded him with before he was forced out, his salary was around $200,000). The reports of executives intensely suspicious of Stahl’s perceived slowness, over-shooting, and incorrigible insistence on working with incomplete continuities so that parts of the script arrived throughout production, reveal a growingly inflexible system impatient with his methods, but also a director adept at getting his way. By the time of Universal’s financial crisis, which led to the Laemmles being forced out, Stahl, though holding the studio’s most expensive contract, found himself in an increasingly difficult position: viewed, despite his reputation and box-office successes, as an expensive dinosaur by the incoming economic rationalisers. The years between Magnificent Obsession and When Tomorrow Comes show evidence of this, with only one film made at the studio, the comedy-melodrama hybrid Letter of Introduction (1938), Stahl’s only other work being the one-off loan-out return to MGM to produce and direct Parnell (1937) in order to pay off the film that he still owed them when he left in 1927 for Tiffany-Stahl.

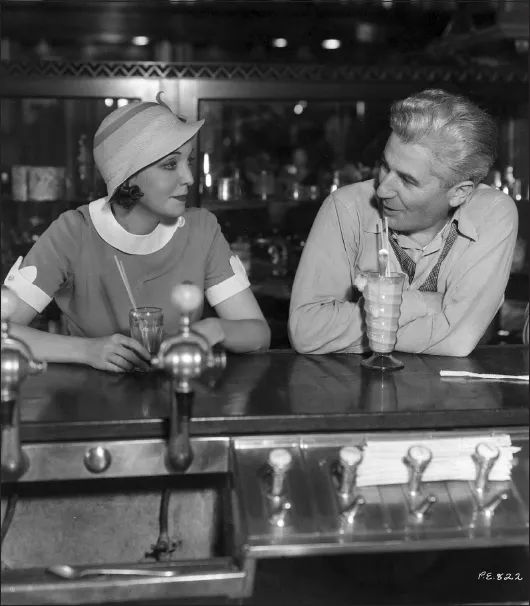

Stahl off set, with ZaSu Pitts, during the production of Back Street (1932).

Stahl departed from Universal in late 1939, leaving unmade an interesting project, Bull By the Horns. There followed activity mirroring his immediate pre-Universal time when, after leaving Tiffany-Stahl, he announced plans for independent production. Trade papers such as Independent Exhibitors Film Bulletin, Motion Picture Daily, Motion Picture Herald, Film Daily, and Boxoffice, now reported negotiations for distribution deals, predominantly with United Artists, and a one-picture deal with James Roosevelt’s Globe Productions that never eventuated. There were also reports of Stahl buying rights to novels, and viewing dramas in New York, but, after further rumours of a return to MGM, he went to Columbia on the one-film deal that resulted in the comedy Our Wife (1941). This period of indecision ended in June 1941 when Stahl signed with Twentieth Century-Fox what the Motion Picture Herald (21 June 1941, 40) said was a “producer-director deal for two years”.

Stahl on set, directing Myrna Loy and Clark Gable in Parnell (1937).

This signing, with further extensions, culminating in a seven-year contract in February 1946 (Motion Picture Daily, 7 February 1946, 5), began his career’s last phase, in which he worked uninterruptedly at Fox up to his death in 1950. Here, as director, but not as producer – if MPH was correct about the contract’s terms, Stahl must have been disappointed to find himself constantly assigned overseers – he made nine studio-assigned films in a wider variety of genres than before: Immortal Sergeant (1943, war), Holy Matrimony (1943, comedy), The Eve of St Mark (1944, war), The Keys of the Kingdom (1944, drama), Leave Her to Heaven (1945, noirish version of the woman’s film), The Foxes of Harrow (1947, historical melodrama), The Walls of Jericho (1948, early twentieth-century melodrama), Father Was a Fullback (1949, family comedy), and Oh, You Beautiful Doll (1949, musical). Leave Her to Heaven is perhaps the only one that has a secure place in the critical canon, but, as the essays that follow argue, Stahl’s last phase produced films that demand critical reappraisal.

Now seen as a veteran director, Stahl was subject to executive vicissitudes, being given and then taken away from various projects, most famously Forever Amber: a hugely publicised and controversially titillating Technicolor subject that he was awarded after the considerable box-office and critical successes of The Keys of the Kingdom and Leave Her to Heaven. Stahl began shooting this with Zanuck’s protegée, Peggy Cummins, in the title role, a project that faltered when Cummins proved too inexperienced for the role, leading to her replacement by Linda Darnell and Stahl’s by Otto Preminger, though Stahl, despite being taken off the film, seems not to have been blamed for the production difficulties.*

He was clearly valued and financially well rewarded at the studio, his salary rising from $80,500 in 1944 to $172,250 in 1946 and $195,000 (more than Henry King, Henry Hathaway and Otto Preminger) in 1948. His films were generally good box-office, and strongly advertised, with their director promoted as being particularly skilled in bringing popular novels to the screen. Though much occupied with studio assignments, Stahl – probably in an attempt to push the studio into adding production to his direction – developed some interesting projects that unfortunately never progressed. He developed material for a biopic of the early-18th century English actress Anne Oldfield, which emphasised his continuing interest both in theatre, and more generally – like the earlier project dropped at Columbia, The First Woman Doctor, a biopic of Elizabeth Blackwell MD – in the lives of women. There were also unfulfilled personal developments of a domestic comedy, called $25,000 A Year, and what would appear to be a very unconventional musical, temporarily referred to as “Cavalcade of American Music from the Times of the Pilgrim Fathers up to Modern Song”. Edwin Schallert described the former as illustrating Stahl’s old penchant for “leaping in on the heels of the news” by creating a presumably satiric comedy about rich people trying to adapt to a speculation attributed to F.D. Roosevelt that in the future the moneyed class’s incomes might be limited to the $25,000 of the proposed title (Los Angeles Times, 1 May 1942, 39). Also early on at Fox, Stahl researched a biopic of Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labour who, it should be noted, before we attribute radical views to Stahl, while fighting for workers’ rights, vigorously opposed socialism and the radical Industrial Workers of the World.

This emphasis on Stahl’s unofficial projects, which underlines aspects of his ambitions that did not fit the Fox frame, should not divert attention from the various successes, by no means confined to the best known of his films, of his final years.♦

Bruce Babington

* This protracted episode of conflict over Forever Amber is discussed and documented in detail by Chris Fujiwara in his book on Otto Preminger, The World and its Double (Faber, 2009) – obviously with more of a focus on the incoming Preminger than the departing Stahl. Peggy Cummins was an inexperienced actress brought over from Britain for this film, very different from the experienced stage and screen actresses with whom Stahl had mostly worked hitherto; but she did later give some memorable film performances both in Hollywood (Gun Crazy, 1949) and back in Britain (Hell Drivers, 1957). It is notable that both her co-star, Cornel Wilde, and her replacement, Linda Darnell, worked later for Stahl on The Walls of Jericho.

![]()

A Lady Surrenders

Universal Pictures. 6 October 1930. 94 minutes.

D: John M. Stahl. P: Carl Laemmle jr., E.M. Asher. Sc: Gladys Lehman, from the novel Sincerity: A Story of Our Time [1929] by John Erskine. Dial: Arthur Richman. Ph: Jackson Rose. Sets: Walter Kessler. Ed: Maurice Pivar, William L. Cahn. Sound: Joseph R. Lapis, C. Roy Hunter.

Cast: Genevieve Tobin (Mary), Rose Hobart (Isabel), Conrad Nagel (Winthrop), Basil Rathbone (Carl Vaudry), Carmel Myers (Sonia), Franklin Pangborn (Lawton), Vivian Oakland (Mrs Lynchfield), Edgar Norton (butler), Grace Cunard (maid).

The romantically suggestive title A Lady Surrenders was later changed to the more judgmental Blind Wives, though the original title is the one that has survived. The Library of Congress holds a 35mm print, which appears to be the only surviving copy.

A Lady Surrenders (1930) is a pivotal film in Stahl’s career: it was his first talkie, and his first project at Universal Pictures, where he returned to directing after two years acting solely as a producer at Tiffany-Stahl. Though handsomely and fluently crafted, it plays as a rough draft or warm-up for the trio of rich, troubling melodramas that would follow: Seed (1931), Back Street (1932), and Only Yesterday (1933). In these three variations on a theme, women are caught between old-fashioned ideals of devotion and self-sacrifice and modern promises of independence and moral latitude, gallantly facing up to the disappointments and limitations of their lot. A Lady Surrenders hints at the ambivalence towards marriage and romance that would develop in Stahl’s next project, but retreats into more conventional plot mechanics; it is one of those films whose most interesting moments seem either unintended or unfulfilled.

Like so many of Stahl’s films of the period, when he was anointed as one of Universal’s prestige directors during the ambitious tenure of Carl Laemmle, A Lady Surrenders announces its literary pedigree up front. The source was John Erskine’s 1929 novel Sincerity: A Story of Our Times. Erskine was a remarkably distinguished and prolific man: a humanities professor at Columbia College (now Columbia University, in New York), where he founded the influential “Great Books” programme; a musician, composer, and president of the Juilliard School of Music; and an author of around a hundred books, ranging from the popular Private Life of Helen of Troy – which was promptly snapped up by Hollywood in 1927 – to the philosophical essay “The Moral Obligation to be Intelligent”. Sincerity centres on a married couple, Winthrop and Isabel Beauvel, and the complications that ensue when Isabel anonymously publishes an essay titled “Sincerity”, attacking the secretly stifling conditions of outwardly happy marriages. Confusing matters further, when she receives a letter in response from her own husband, she asks her friend Mary to meet him in her place, posing as the author of the article.

Conrad Nagel and Rose Hobart, rehearsing for director John M. Stahl.

The film, adapted by Gladys Lehman with dialogue by Arthur Richman, discards the theme of sincerity, but otherwise hews to this premise. Here, the irritated novelist wife Isabel (Rose Hobart) fires off an essay called “The Marriage Trap”, in which she argues: “Marriage is just a trap for women, baited with protection chiefly, companionship and affection…Why can’t a woman have these things, these necessities, without losing her freedom?”

This is strong stuff, but it is a spark ...