![]()

Section 1

A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW

![]()

1

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

CRITICAL THINKING

Stella Jones-Devitt and Liz Smith

This chapter explores some of the contrasting definitions of critical thinking. It considers the background, development and possible boundaries of critical thinking as a subject area. It also raises questions about the purpose and politics of critical thinking studies taught in higher education. Exercises are included to facilitate your personal construction of the characteristics of critical thinking.

Chapter aim

- To provide an overview of some key debates about critical thinking

Learning outcomes

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- explore the background and development of critical thinking

- critically discuss some of the contrasting definitions of critical thinking

- identify possible boundaries of critical thinking as a discrete subject area and body of knowledge

- critically evaluate the purpose and politics of contemporary ‘Critical Thinking Studies’

Background and development

Critical thinking is often linked with a multitude of synonyms such as ‘creative thinking’, ‘lateral thinking’, ‘problem-solving’, ‘decision-making’ and ‘reasoning’. Given these different descriptors, origins of critical thinking are also contested, ranging from those who trace it back to the times of Socrates and the Ancient Greeks in which assumptions that those in ‘authority’ had sound knowledge and insight were challenged, to those who view critical thinking as a fundamentally modern construct. This latter perspective is held by Boychuk Duchscher (1999) who contends that critical thinking evolved from the efforts of the early twentieth-century Frankfurt School of Critical Social Theory. This School of thinking emerged in response to the unsuccessful integration of capitalism and socialism in Eastern Europe which raised much dissention about the lived experience of everyday lives and the relationship to belief systems; out of which came the Critical Social Theorists’ views about critiquing ideology as a form of social oppression rather than accepting it as an all pervading force.

Daly (1998) draws attention to the Middle Ages and the teachings of Thomas Aquinas who systematically explored each part of any idea with rigorous scrutiny before letting his thoughts develop further. Renaissance thinkers also began to think that human life should be subject to more examination, especially in those areas concerned with religious matters, art, nature and freedom. Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries several scholars emerged such as Francis Bacon and Thomas More in England. Bacon is credited with writing the first book concerned explicitly with critical thinking entitled ‘The Advancement of Learning’ (1605) in which he described several ‘false idols’ that impinge upon peoples’ ability to think if left to their own devices. Many of these idols helped to form incorrect assumptions, especially in relation to misuse of words, blind acceptance of convention, self-delusion and poor instruction. Thomas More’s notion of ‘Utopia’ (1516) envisaged a society without private property that he advocated as an idyll. Heywood (2004) suggests that More’s work could be viewed as satirical rather than propagandist. Heywood also indicates that such notions of utopian society emerged at this time due to faith in reason that encouraged: ‘thinkers to view human history in terms of progress, but it also, perhaps for the first time, allowed them to think of human and social development in terms of unbounded possibilities’ (p. 365).

Within this historical period of Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, philosophers and political thinkers eschewed religious dogma and metaphysical forces as the key drivers for existence, instead basing their ideas upon human rationalism and reason. Considerable activity revolved around French thinkers like Descartes, Diderot and Rousseau who focussed on rationalist explanations in which they argued that the workings of the physical and social worlds could be understood by an examination of reason alone. Descartes is credited with writing the second explicitly stated book of critical thinking ‘Rules for the Direction of the Mind’ (1628) in which the need for a systematic set of principles to guide the mind and thinking processes were espoused. From this work, Descartes went on to explore possible dichotomies of mind and body, with the mind being defined as a thinking machine separate of physical functioning. Descartes proposed that both should be treated as independent systems rather than as one, thus spawning an approach known as Cartesian Dualism upon which much of modern medicine is predicated. These views contributed to an examination of existing political orders and underpinned many radical and revolutionary doctrines. Heywood (2004) notes that key thinkers began to appreciate the potential of human beings for self-determination or to: ‘the extent that human beings possess the capacity to understand their world, they have the ability also to improve or reform it’ (p. 21).

Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a time of great challenge to existing social orders and hierarchies. From Hobbes and Locke in England, to Machiavelli in Italy, to Voltaire in France; all recognised that disciplined human minds were well-placed to question the real agendas of the establishment in political power and submit those in privilege and authority to real scrutiny and accountability. Given the context of these times, it is hardly surprising to find that both the American Revolution (1776) and French Revolution (1789) occurred during this period, in which those in privilege and power faced brutal scrutiny and questioning of their actions. The rationale underpinning these events were explored in the American Thomas Paine’s seminal work, ‘The Rights of Man’ (1791) in which the justification for both revolutions was made as being actions undertaken by conscious and critical efforts to remove inequalities fostered by the privileging of heredity and monarchy. Throughout the revolutionary period and subsequent aftermath, the power of collective critical thought became recognised as an enduring force for meaningful political change. This spawned a new direction in which critical thinking and reason were applied as tools for specific domains in the pre-industrialised world; examples include Adam Smith’s economic treatise ‘The Wealth of Nations’ (1776) and Immanuel Kant’s application to reason, per se, in his ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ (1781).

The nineteenth-century industrial era saw critical thinking being applied directly to prevailing economic issues with both Marx and Engels using reasoning tools to critique the emergence and possible consequences of the capitalist state and to scrutinise the power of manipulated thought. A central tenet of Marx’s analysis was the explanation of the status quo and the relationship to class consciousness. Marx and Engels alluded to notions of ‘False Consciousness’ in which a dominant ideology or set of ideas, propounded by the ruling class, become so powerful that the dominated class fails to recognise their own exploitation and consequently remained uncritical and unaware of any power to resist or challenge. The emergence of a range of social sciences, grounded in reason, yet removed from the deductive logic dominating the physical sciences, added further weight to the growing use of critical thinking to unpack the processes of both knowledge construction and its privileging; also being applied to the unconscious mind through the work of Sigmund Freud and other psychoanalysts.

In the early twentieth century, the educationalist John Dewey added a further dimension to the development of critical thinking, suggesting that it could be linked to higher-order sense making in a world where ambiguity caused dilemmas that required consideration of alternatives. Dewey indicated that critical thinking was one element of a broader reflective framework involving assessment, scrutiny and conclusion; a process that should be followed if effective judgements were to be made. According to Daly (1998) Dewey felt that the main purpose of critical thinking was to introduce an appropriate degree of scepticism and rigour alongside suspension of judgement when necessary. McKendree et al. (2002) add that Dewey saw critical thinking as an essential tool for the furtherance of viable and meaningful democracies. This approach also aligns him with the Critical Social Theorists of the early twentieth century mentioned previously, who saw ideological critique as central to understanding routes of social oppression.

Clearly the contributions of certain historical figures have aided the overall development of critical thinking, yet many groups are not represented at all in traditional historical analyses. Difficulties arise when trying to deduce who has been left out of the historical documentation and why. A pattern for inclusion is prevalent in respect of the characteristics of the key critical thinkers presented, in that they were: men, of privileged social background, predominantly white and well-educated.

Activity

- In your opinion, who is the most well-known critical thinker in contemporary times?

- Why is there a dearth of women critical thinkers in history?

- Identify someone from your own professional area who is a critical thinker

Definitions of critical thinking

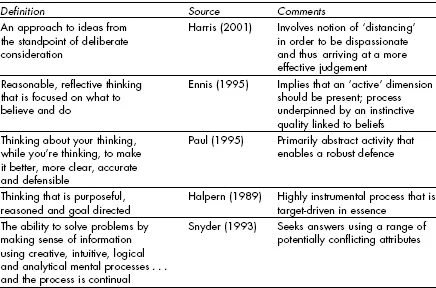

Given this historical predominance of men from privileged backgrounds within critical thinking, it still appears to be dominated by similar theorists in contemporary times. Many commentators have sought to provide a definitive view of critical thinking yet there is no overall consensus of opinion; merely a collection of responses that can be clustered into several domains. Table 1.1 provides some of the many contrasting definitions of critical thinking to consider.

Even these five examples show considerable differences between two continua. The first continuum concerns whether critical thinking is an instrumental or non-instrumental activity. Certain theorists see critical thinking as a highly instrumental activity in which outcomes are linked to discernible goals and targets. Halpern (1989) in particular, defines critical thinking as being goal-driven in essence, whereas Paul (1995) sees it as an abstract non-instrumental activity to defend. The other continuum in which opinion is polarised, concerns whether thinking has to have an ‘active’ dimension or end-point. Harris (2001) implies that thinking is about the process of distancing from specific standpoints in order to arrive at the best possible accommodation which may, or may not, involve acting out one’s thoughts. In this definition, the whole process is underpinned by reflective thinking. This contrasts with Ennis’ (1985) assertions stating that thinking should lead to enactive processes.

Table 1.1 Definitions of critical thinking

These continua are mediated by whether the process of critical thinking is viewed essentially as engagement in problem-solving as opposed to sense-making per se. A problem-solving approach aligns with active and goal driven responses that are primarily time-limited and discreet activities, whilst sense-making can be an abstract and continuous process linked to the thinker rather than to specific tasks undertaken (see Figure 1.1). After considering many contrasting views, the broad definition of critical thinking that underpins the ethos of this book comprises:

Making sense of the world t...