![]()

The Inclusion and Every Child Matters agendas

This chapter sets the scene for the rest of the book. It explains how:

- the inclusion debate has developed to encompass the notion of all schools being part of a flexible continuum of provision

- the Every Child Matters agenda is unfolding alongside inclusion

- the chapters in the book are set out to illustrate how an inclusive education service is being developed across schools and services

The convoluted path of inclusion

After many years of argument about what inclusion should mean with regard to pupils who have special educational needs, there is a growing consensus about how the concept of inclusion should be defined. In the past, the debate centred almost entirely around a small percentage of pupils with the most significant needs and where their education should take place. This is ‘inclusion’ in the narrow sense of ‘placement’. After a quarter of a century of unproductive and heated argument, there is, at last, widespread agreement that inclusion is not about a place at all, but describes a process.

All schools need to work hard at making pupils feel they are part of the school community and have something to contribute. This is particularly necessary where, for a variety of reasons, including having special educational needs, pupils may find it harder to be accepted by their peers and appreciated for what they have to offer. Any type of school may or may not be an inclusive school, depending on the ethos of the school, and how staff try to accommodate and value all pupils. Special schools, in common with mainstream schools, have encountered the challenges of being asked to take on pupils with needs that are outside their experience, and have had to find ways of making sure the school adapts to provide for such pupils, as well as it does for the rest of its population. This means that special schools do not stand outside inclusion, as is sometimes implied; they are part of it.

The concept of inclusion has moved on from meaning all pupils being included in mainstream schools to the much more productive idea of all schools working together as part of an inclusive education service. Nor is it only schools that are part of inclusion. Advisory and support services too have a significant role to play in supporting pupils with special educational needs, wherever they are being educated.

The lengthy debate around the meaning of inclusion has hindered the development of a coherent education service, within which there is agreement about how to meet the whole range of needs, from the vast majority of pupils who require varying levels of support in mainstream schools, right through to those whose needs are so severe that a 52-week placement may be considered. Instead, local authorities and individual schools have been inclined to devise their own ways forward, outside any national framework.

Examples from across the range of provision are given in the following chapters. The case studies have been chosen to illustrate some of the many ways in which schools, both mainstream and special, as well as advisory and support services, are moving forward in new ways to embrace the concept of working together to meet the needs of all pupils. A range of innovative practices is emerging, that illustrate some of the many and varied ways that pupils with special educational needs are being included in a very real sense. An added impetus to this work has been the unfolding of the Every Child Matters agenda, with its emphasis on placing children and their individual needs at the heart of what schools do, rather than thinking in terms of what is most convenient for the institution.

Terminology and SEN

The term ‘special educational needs’ was used by the committee set up in the 1970s, under the chairmanship of Mary Warnock, to look at the education of ‘handicapped children and young people.’ The term was used widely on its own until the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act of 2001 brought the two terms ‘SEN’ and ‘Disability’ together. Although the expressions are not synonymous, there is considerable overlap between them. The Disability Rights Commission’s Code of Practice for Schools (2002) explains that:

Pupils may have either a disability or special educational needs or both. The SEN framework is designed to make the provision to meet special educational needs. The disability discrimination duties, as they relate to schools, are designed to prevent discrimination against disabled children in their access to education. (Paragraph 4.10)

Further shifts in terminology can be detected through recent reports from Ofsted:

- Special educational needs in the mainstream (2003)

- Special educational needs and disability: towards inclusive schools (2004)

- Inclusion: does it matter where pupils are taught? Provision and outcomes in different settings for pupils with learning difficulties and disabilities (2006)

In the last of these three reports, the term ‘SEN’ or ‘SEN and Disability’ is replaced with ‘Learning Difficulties and Disabilities’ (LDD). The explanation for this is given in the report itself:

The term LDD is used to cross the professional boundaries between education, health and social services and to incorporate a common language for 0–19 year olds. In the context of this report, it replaces the term special educational needs. (Page 21)

Ofsted has a valid point. With the roll out of Every Child Matters, a common language across services, particularly education, health and social care, is much needed. The difficulty is that the term ‘SEN and Disability’ is enshrined in law and the DfES will continue to use it. For the sake of simplicity, ‘SEN’ will be used throughout this book.

Questions for reflection

- What is your own view of inclusion?

- Do you think it is time to replace the word ‘inclusion’ in the context of special educational needs?

- Does the term ‘SEN’ itself need replacing, and if so, have you any suggestions as to what should be put in its place?

The background to the inclusion and Every Child Matters agendas

In schools, there is often a feeling of a lack of cohesion between government policies and a sense of despair when some of them seem contradictory; for example, the need to raise standards for all can be accepted as a general principle, but the way to set about achieving this has caused much anxiety, not least for those concerned with the progress of pupils with SEN. Personalising the curriculum and focusing on the needs of every individual, sits uncomfortably with the notion that all pupils of the same age should be tested on the same day. Performance tables may have been renamed ‘Achievement and Attainment Tables,’ but they still measure the attainments of some, rather than recognising the achievements of all pupils, whatever the level they have reached.

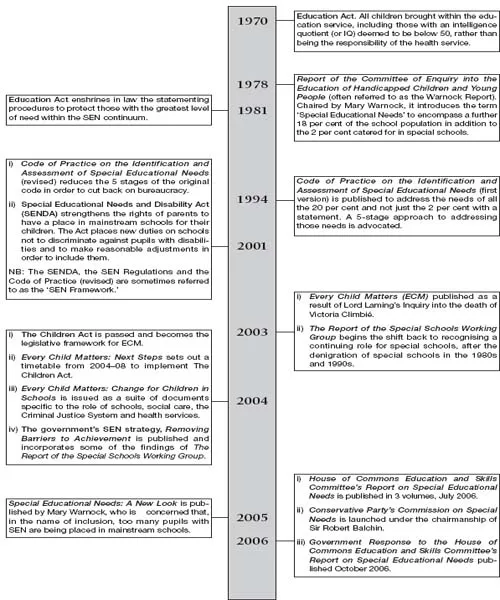

However, two agendas that do sit comfortably together are those of inclusion and Every Child Matters (ECM). To understand how the present position has been reached, both in terms of the debate about inclusion and the emergence of ECM, it is worth remembering some of the more recent landmarks that have led to the current situation, from the time of the 1970 Education Act.

Developments in ECM and SEN, 1970 – 2006

Making ‘inclusion’ include all provision

In tracking the evolution of the meaning of inclusion, it is worth remembering how there was a shift from the use of the term ‘integration’ in the 1980s, to using the term ‘inclusion’ in the 1990s.

Integration and inclusion

Integration was about integrating individuals into mainstream schools, with the onus being partly on the pupil with SEN to adapt to a mainstream environment.

Inclusion was used to signal a change as to how schools themselves could adapt to meet the needs of all the pupils who come to them.

The 1990s was a time when there was increasing awareness of the need to provide lifts and ramps to help wheelchair users and others with mobility problems to access buildings, and this included schools. Those with sensory impairments, the deaf and the sight impaired, benefited from technological advances that made it possible for some to access a mainstream curriculum for the first time. But a very sensible and realistic move to include more pupils in mainstream schools became for some enthusiasts of mainstream provision, proof that all could be included in mainstream education. This position overlooks the very real differences between those who need physical or technological adaptations to access the curriculum, and those with other kinds of needs, such as cognitive impairment, where no such adaptations are available. Warnock, in her introduction to Farrell’s book, Celebrating the Special School says:

What has been wrong with the policy of inclusion has been the idea that if some children with special needs can flourish in the mainstream they all can. (Farrell, 2006: v)

Although the new century has seen the growth of a common understanding about the need to maintain a range of provision, there is still a minority who would argue that, where inclusion appears not to be working, the fault lies entirely with schools who have failed to adapt sufficiently to meet all needs. In fact, most mainstream schools have worked extremely hard to include a wider range of pupils and have done so with a considerable degree of success. However, seeing it just in terms of what schools are achieving is only looking at one side of the issue. For it is not just a matter of how far schools have been successful in welcoming pupils with more complex needs, but whether the pupils themselves are comfortable in a mainstream environment. The idea that the greater the child’s difficulties, the more it may be necessary to adapt the environment to suit their needs, is one that will be explored throughout this book.

A further aspect of the inclusion debate has been raised by those who have treated inclusion in mainstream schools as a human rights issue. This goes further than saying that there should be a right to choose a mainstream education. Instead, it puts forward the view that all schools must be prepared to accept all children and, as special schools stand in the way of this happening, special schools should close. As well as assuming that all pupils could have their needs addressed in a mainstream environment, including specialist teaching and equipment, and the therapies and medical support some of them depend upon, this viewpoint deprives parents of choice. It used to be the case that parents of children with SEN, had to fight for a mainstream place. Today, the situation has changed and parents are just as likely to be fighting for a place for their child in specialist provision. As Warnock says about inclusion in her latest publication, Special Educational Needs: A New Look:

Let it be redefined so that it allows children to pursue the common goals of education in the environment within which they can best be taught and learn. (Warnock, 2005:54)

If this is a matter of human rights, then surely it should be about the right of every child to receive an education appropriate to his or her needs.

In its SEN Strategy, Removing Barriers to Achievement, published in February 2004, the government tried ...