eBook - ePub

Skills in Business

The Role of Business Strategy, Sectoral Skills Development and Skills Policy

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Skills in Business

The Role of Business Strategy, Sectoral Skills Development and Skills Policy

About this book

Johnny Sung and David Ashton are two of the leading scholars in the area of skills. This book combines challenging theories with cutting edge research in a way that should bring skills to life for students. I strongly recommend it for anyone researching or studying in this area.

- Irena Grugulis, Leeds University Business School

"A much needed contribution to the complex debate of how skills can best be utilised to enhance company performance, with particular emphasis on an innovative sectoral approach. It is a model of clarity in its presentation of the authors' conceptual models using a historical narrative as well as comparative case studies in both the UK and Singapore."

- Bert Clough, Leeds University Business School

Public skills policy in most market economies in the last forty years made one repeated error, time and again. We seem to be unable to learn from those mistakes. Consistently, public policies view a wide range of economic and social issues e.g. low productivity, low-skilled jobs, low wage, inequality and in-work poverty as the consequence of skills deficits and a lack of qualifications held by individual workers. Whilst mis-diagnosing the source of the problems and failing to deliver any effective change, public skills policies continue with a policy prescription of 'more skills' and 'more degrees'. If we have not solved the problems with this decade-old approach, why should the same medicine work this time?

- Irena Grugulis, Leeds University Business School

"A much needed contribution to the complex debate of how skills can best be utilised to enhance company performance, with particular emphasis on an innovative sectoral approach. It is a model of clarity in its presentation of the authors' conceptual models using a historical narrative as well as comparative case studies in both the UK and Singapore."

- Bert Clough, Leeds University Business School

Public skills policy in most market economies in the last forty years made one repeated error, time and again. We seem to be unable to learn from those mistakes. Consistently, public policies view a wide range of economic and social issues e.g. low productivity, low-skilled jobs, low wage, inequality and in-work poverty as the consequence of skills deficits and a lack of qualifications held by individual workers. Whilst mis-diagnosing the source of the problems and failing to deliver any effective change, public skills policies continue with a policy prescription of 'more skills' and 'more degrees'. If we have not solved the problems with this decade-old approach, why should the same medicine work this time?

This book examines the role of public skills policy from a completely different perspective. It starts by challenging the lack of a systematic analysis of the link between skills utilisation and business strategy, and provides a new model for fresh thinking. The book extends this theoretical analysis to examine the implications for the sectoral approach to skills development as a more effective form of public skills policy.

David N. Ashton is Emeritus Professor at the University of Leicester and Honorary Professor at Cardiff University.

Johnny Sung is at The Institute for Adult Learning, Singapore Workforce Development Agency, Singapore.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Skills in Business by Johnny Sung,David N Ashton,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Skills. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE CHALLENGES FACING SKILLS POLICY IN THE 21st CENTURY

As a matter of fact, capitalist economy is not and cannot be stationary. Nor is it merely expanding in a steady manner. It is incessantly being revolutionized from within by new enterprise, i.e., by the intrusion of new commodities or new methods of production or new commercial opportunities into the industrial structure as it exists at any moment. Any existing structures and all the conditions of doing business are always in a process of change.

J.A. Schumpeter ([1942]2003: 31)

Overview

The aim of this chapter is to further our understanding of the national context within which business leaders and the leaders of large public organisations make decisions about the business strategy, which in turn shapes the skills they demand and the ways in which they use them. We highlight three major factors that shape this national context. The first is the nature of the opportunities that are available to the business or organisation leaders to pursue their objectives, which in the case of businesses is to deliver a profit. These opportunities are structured by the position of the company in national and increasingly global markets. This is also the case for political leaders as it is their remit to help business deliver economic growth and create quality jobs. This international context therefore plays an important part in influencing the type of approach that the nation adopts to skills policy.

The second is the political struggle within the country, the alignment of interest groups and political parties and the outcome of this struggle for power that shapes the dominant ideology and institutional framework through which the various components of the national approach to skills policy, including the vocational education and training (VET) system, are delivered. The third major factor is the type of productive system that dominates the economy at any one point in time. We use the term ‘productive system’ to refer to the types of market the company chooses to compete in and the ways in which the process of production is organised, the type of technology it uses and the ways in which it manages employees. This has a very important influence on shaping the level of skills demanded by employers in order to operate their businesses and the ways in which they use those skills.

These factors interact in a specific historical context, which itself affects the outcomes in terms of how the economy develops. To illustrate this we examine how approaches to skills policy change in three different countries that industrialised at different points in time. Each has passed through a distinct series of phases during which the interaction of these forces created distinctive challenges and produced different outcomes in terms of the skill policy that they adopted and which they have modified over time. This interaction also gives rise to different academic theories that seek to explain what is happening and what the appropriate policy solution would be. Our argument here is that the UK and other Anglo-Saxon countries developed a policy based on reliance on the market to deliver skills and informed by human capital theory that may have been appropriate at an earlier stage of economic development but is now failing to meet the demands of an economy facing increasingly competitive conditions in a global market.

What this exercise shows is that the type of policy framework adopted by the state (and the academic theories that underpin it) interacts with the productive system and influences the direction in which the economy moves. The intention of the analysis is to provide the reader with a greater understanding of the forces that shape policy and the business strategies that employers adopt. Just how these factors interact at the level of the firm and so shape the demand for different levels of skills and the ways in which employers use them is the task of the main body of the book. Once we have made headway in this task we return in the final chapters to re-examine the policy process and the potential we have for improving the effectiveness of policy.

Introduction

The above quote from Schumpeter reinforces the main message of this chapter, namely that economies are constantly in the process of change. Yet at any one point in time they are characterised by specific types of productive systems, be they early industrial mass production, Taylorist mass production, where a detailed division of labour was combined with assembly line technology, mature mass production where high-performance working practices were combined with modern mass production technology, or knowledge-intensive production. From our perspective each of these creates specific types of skill demands. In response to these, politicians create policy frameworks to deliver what they perceive to be the skills required. Our argument here is that the most recent change from Taylorist mass production to globalised forms of mature mass production and knowledge-intensive production has shifted the point of political intervention from the supply side to the demand side. (This is illustrated in Figure 0.1, where the intervention shifts from the right-hand side of the diagram to the left-hand side.) While other countries have sought to adapt their frameworks to these changing demands, especially the most recent industrial countries such as the Asian Tigers, the UK and some other Anglo-Saxon countries have failed to adapt their policy frameworks in an appropriate manner.

In order to show empirically how these relationships change through time we have identified a series of stages that symbolise major changes in the systems of production. Economies and societies are never self-contained systems, so we start by briefly examining the international context which shapes the ways in which these relationships play out at the national level. Then in each stage at the national level we outline the dominant type of productive system that generated a particular type of skills demand. Next, we examine the theoretical ideas and policy framework through which politicians respond to these skill demands. Finally, we explore the effectiveness of these policy responses.

While the processes we are examining are universal, the precise form taken by policy responses and, to a limited extent, the demand for skills generated by the productive system are also shaped by the values and institutional structures of each society. Here we are talking not just about the VET systems but also the broader institutions that structure relations between the state, employer and union organisations and the broader legal framework within which they are embedded. These not only affect the policy response of governments to changes in skill demand, they also have an impact on the business strategies that are crucial in shaping those changes in demand, a reciprocal influence.

So in terms of Figure 0.1, what we witness over a time is that changes in economic, political and cultural institutions result in changes in business strategies, which in turn trigger changes in the productive system. These create new demands on employees in terms of the level of skill required to operate within the business and the ways in which those skills are used. During the 1950s and 1960s a policy response that just acted on the right-hand side of Figure 0.1 and increased the supply of skills was appropriate to meet the demands of the productive system, but over time, as the business strategies of employers have changed the need has arisen for an approach that tackles skills policy from the left-hand side. As we shall see, other countries have already moved much further in this direction.

The countries we use to illustrate this are the UK to represent the Anglo-Saxon countries, Germany for the Germanic countries that use the dual system and Singapore for the developmental states of South-East Asia. All of these countries are responding to the same changes in the global economy, but the way in which employers have responded (namely the productive system) is influenced by the policy environment within their political boundary. In a short treatment of the issues such as this we cannot go into detail about all of the three models, but we can use them to illustrate the ways in which these global changes impact on the productive system and the associated demand for skills in different institutional contexts.

Three contrasting approaches to skills policy

To place these divergent approaches in context we provide a brief description of the historical evolution of these approaches to skills policy. The UK being the first industrial nation in world markets never developed a coherent policy approach to employee training. The early industrial training was governed by legislation concerning the master–servant relationship with its origins in the guild system. Abuses of this by early industrial employers led to legal regulation of the conditions of child and female labour, but in general employers and unions were left to agree among themselves on the regulation of training and where unions were ineffective employers were left to control the process of training. For the professions, these were regulated during the late 19th century by their professional bodies. It was not until the early 20th century that, with increasing competition from the USA and Germany, the government started to initiate moves towards some form of regulation of industrial training. These culminated in the tri-partite system of industrial training boards after the Second World War but they were largely dismantled and an attempt at government direct regulation ended in the 1980s. Following that the UK relied on the ‘free market’ to deliver training and skills. This does not mean that these activities were not regulated at all, only that the regulations and legal framework meant that employers were left to determine the levels and types of training offered subject to the restrictions laid down in employment law and to any conditions that unions or professional bodies were able to impose.

Germany industrialised after the UK and USA but did so very rapidly and by the early 20th century was a major contender in world markets and a serious political threat to the UK. However, because the process of industrialisation took place within the framework of the old guild system, the apprenticeship remained as a strong institution that shaped the training of those entering craft work. At the national level the unions developed a strong base. This system was rebuilt after the Second World War when there was an urgent need to regenerate German industry and help the country regain its position in world markets. To this end the government, unions and employers agreed on a strong institutional framework to govern the apprenticeship, which was to embrace not just narrow vocational training but also more a broadly based system of schooling for citizenship. This ensured that young people had a thorough training comprising both off-the-job college education in theory and practical on-the-job training under the direction of a ‘Meister’, a qualified person responsible for overseeing their training in the workplace. The system was overseen by the Federal Institute for Vocational Training (BIBB) responsible for research and development and for ensuring that the system was constantly modified to accommodate changes in the industrial and occupational structures.

In Singapore the situation was very different. From its birth after the Second World War as a small trading nation with high levels of poverty and no natural resources it faced a difficult task to break into world markets and stimulate the process of industrialisation. From the start the government took an active role in attracting foreign capital and providing the infrastructure that would encourage employers to grow their businesses. Initially this was to take advantage of the low-cost labour but as the economy developed the government actively steered the economy into the production of higher value-added goods and services. To achieve this it provided higher levels of education and training and delivered higher standards of living until today it has one of the highest standards of living for its citizens in the world.

Changes in our understanding of national business and skills policy frameworks

Even such a cursory examination of these different approaches to skills or workforce development highlights three major sources of change that shape national approaches. These are the international context in which the policies are formed, the outcomes of the national political struggles and the type of productive system that characterises the economy. The international context is important because, as we will show, it shapes the country’s competitive position in world markets and provides the context in which skills policy is to deliver its outcomes. All too often the study of VET systems fails to take this into account and these systems are treated as if the only factor that affects their development is the national political context. While the national context is important, it cannot explain why some countries have developed highly coordinated systems. These are crucial if the country has to break into existing markets. For politically powerful countries such as the UK in the 19th century they were not necessary as they could forcibly impose their goods on the countries they dominated.

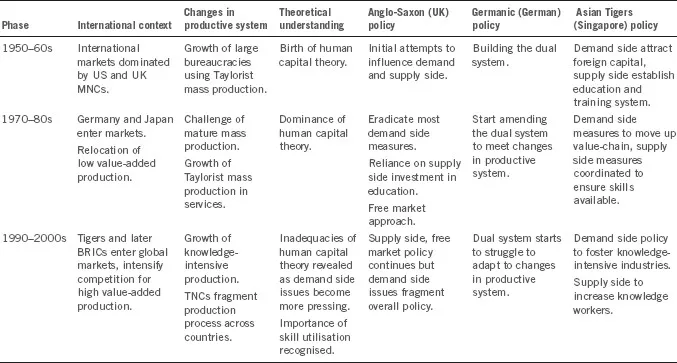

The national political context is important because that provides the resources and ideological guidance for policy makers. The characteristics of the productive system are crucial because this determines the type of skills required by employers. The major changes that characterise the various phases in the development of the productive systems and the policy responses are summarised in Table 1.1. It illustrates in summary form how these various factors change through time and also how our theoretical understanding changes in accordance with them.

Phase 1: 1950s, 1960s

International context

We pick up the story in the post-Second World War period, which contains the origins of the present problems in the Anglo-Saxon world. This was the time when the USA dominated world markets and trade was governed by international institutions such as the World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The objective was to stabilise and consolidate world markets in the pursuit of free trade. In ideological terms the USA was firmly wedded to free-market principles precisely because it was in their interest to remove barriers to trade as it enabled their national companies to grow, exploiting the advantages of mass production in manufacturing companies competing at the leading edge of national markets.

Internationally, the UK was also committed to the free market, competing across a wide range of markets, both at the high end and the low end, but this was in the context of its Empire which it was in the process of losing, thereby exposing UK companies to the full weight of global competition.

Changes in the productive system and skill demands

Within the Western countries during this period the economies were increasingly dominated by large corporations, able to exploit systems of Taylorist mass production to service the growing national markets in the USA and Europe for consumer goods. Where they spread abroad, as many of the large American corporations did, this growth took the form of transplanting the whole production process, sourcing the materials and parts and assembling and marketing the finished product, all within the boundaries of national markets. The result was the growth of large corporate bureaucracies, offering careers for the emergent middle class, from office clerks to administrators, professionals and managers. In addition, in the public sector there was the significant growth of public administration and health care provisions in the UK and in the USA, what Galbraith (1967) referred to as the ‘military-industrial complex’. This rapid growth of white-collar jobs increased the proportion of middle level jobs and created what appeared to be ever expanding opportunities for social mobility, enabling children of the working class, through successful school performance, to enter middle-class careers.

Table 1.1 The impact of changes in productive systems on skills policy

MNC = multinational corporation; BRIC = economics of Brazil, Russia, India and China;

TNC = transnational corporation.

In order to exploit the advantages of the Taylorist system of mass production, new skills in the management of large bureaucratic organisations had to be developed, new systems of accounting introduced and, in addition, new professions such as those of marketing had to be established in order to persuade customers of the value of the products on offer. These created new demands on the education system for highly educated recruits. Further down the hierarchy the burgeoning clerical and administrative jobs in both private and public bureaucracies required relatively high levels of literacy and basic problem-solving skills. The spread of mass production also created a growing demand for the intermediate level skills of maintenance workers and engineers. However, at the base of the hierarchy, the assembly line techniques required large groups of semi-skilled and unskilled operatives. For them the only skills required at the point of entry to the firm were low-level literacy skills, sufficient to understand the rules and regulations of the firm, with other elementary manual skills being acquired on the job. Overall, the introduction of this productive system was making major new demands on the systems of education and training but only from the level of intermediate skills and above.

Theoretical thinking during this period

There was relatively little theoretical thinking to inform skills policy following the Second World War. At that time the countries that had industrialised in the first phase, such as the UK and USA, had reached what was seen as industrial maturity, Germany and Japan were rebuilding their economies, while the third phase countries such as the Asian Tigers had only just initiated the process. Yet there were sufficient cases of industrialisation for academics to provide an understanding of the regularities in the process of economic growth, what Rostow (1960) termed the ‘Stages of Economic Growth’. Other labour economists (Kerr et al., 1960) looked to explain this in terms of a ‘logic of industrialism’, referring to the forces that were driving societies through these stages of growth. One of the most import...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The Challenges Facing Skills Policy in the 21st Century

- 2 The Long Wait is Over: Linking Business Strategy to Skills

- 3 Technical Relations and Skill Levels

- 4 Interpersonal Relations and Skill Utilisation

- 5 Skills, Performance and Change

- 6 A Sectoral Approach to Skills Development and Public Skills Policy

- 7 Conclusion

- References

- Index