![]()

1

What is coaching?

In this chapter we will look at:

- what coaching is

- the differences between mentoring and coaching

- a variety of coaching models that can be used in schools

- what makes a good coach.

Good teachers can be developed, providing they are working in a supportive and positive environment where it is okay to try things out, make mistakes and then further refine their ideas. They also need to be able to reflect on the issues that are important to them with an encouraging colleague, who will listen and ask key questions to help them find their solution – not the ‘this is the way I do it, so you should do the same’ approach. This, in our view, is the essence of coaching.

In the sixteenth century, the English language defined ‘coach’ as a carriage, a vehicle for conveying valuable people from where they are, to where they want to be. It is worth holding on to this definition when talking about coaching in schools. The staff are the most valuable resource that a school has. They are the people that make the difference to the young learners that come to our schools. We therefore have a duty to help and support each other, to become the best teachers that we can possibly be. Coaching is a vehicle to do this.

‘The good news is that as a teacher you make a difference. The bad news is that as a teacher you make a difference.’ (Sir John Jones, speaking at the Accelerated Learning in Training and Education (ALITE) conference, 2006)

Teachers are often all too aware of when things are not going well and how they would like things to be – what is often called their ‘preferred future state’. What we often struggle with is how to get there. What do I need to change? What can I do differently? Why is it not working? A coach is a trusted colleague who asks the right questions to help you find your own way to your preferred future state.

It is important to recognise that this is not new, not rocket science, nor is it a panacea. Teachers in schools have been supporting each other in this way for many years. The skills of a good coach will be examined later on but, put simply, they are listening, questioning, clarifying and reflecting. To coach successfully in schools, you do not need vast amounts of training or a certificate – you just need to have experienced it and to have reflected on its value. We are not talking about life coaching here nor about counselling, which are two very different things that should most definitely be left to the experts. It is the simplicity of coaching in a school setting that makes it such a useful, universal and powerful developmental tool. However, it is only a tool – a very powerful one – but one of many that should be stored and used in the professional development toolbox. It would be naïve to believe that coaching is the ‘teacher’s cure-all’.

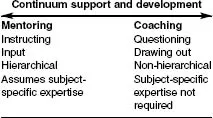

When examining definitions of ‘coaching’ it is clear that there are common threads running through all of them. They all suggest that coaching is a professional relationship, based on trust, where the coach helps the coachee to find the solutions to their problems for themselves. Coaching is not about telling, it is about asking and focusing. This is what separates mentoring from coaching. A mentor is often used when somebody is either new to the profession, for example a teacher in training or NQT, or is new to a particular role in the school. The mentor will have more experience than the person being mentored in that particular role, and so passes on their knowledge and skills. With coaching, the approach is different. It is more concerned with drawing out the solutions to a problem, by effective questioning and listening. It is non-hierarchical and does not depend on any expert/subject specific knowledge. In fact, one of the most successful coaching relationships that we have seen involved a NQT coaching an experienced teacher of nearly 30 years on how to effectively incorporate information and communication technology (ICT) into her lessons.

Case study: Sarah and Jan

Jan was a physical education (PE) teacher with nearly 30 years of teaching experience. She was a good and well-respected teacher, who had recently started teaching English to Year 7. Sarah was an English NQT. Jan had identified that she wanted to make her lessons more engaging by using her newly acquired interactive whiteboard. She didn’t want to attend a course on this but had been impressed with some of the lessons of her colleague, Sarah, who taught next door. Following a school training day on coaching, Jan asked Sarah if she could coach her. The two soon struck up a highly effective coaching relationship, which involved three coaching sessions and two lesson observations – each observing the other. Jan described how she felt at the end of the process: ‘Sarah helped me to clarify exactly what I wanted to achieve, and the steps I had to take to get there. As a result, I now feel confident using my interactive whiteboard and have achieved my goal – to deliver more interesting and engaging lessons’.

It is worth acknowledging that this relationship was an unusual one – in terms of the difference in experience of the coach and the coachee. However, it does demonstrate the non-hierarchical nature of coaching.

Many of the skills of good mentoring and good coaching overlap – and often a blended approach of the two is most effective. When supporting a colleague, it is important not to be constrained by the labels of ‘coaching’ and ‘mentoring’. By this we mean that, if during a coaching conversation it becomes clear that no amount of questioning, reflecting, listening or clarifying is going to move the person on, then sometimes you need to slip into mentoring mode and make a suggestion. There is nothing wrong with this, although we suggest that it may be helpful to be explicit when adopting a different stance by, for example, asking permission of your colleague – ‘Would it be all right if I were to suggest a possible course of action here?’. Alternatively, the coach may be able to tap into the coachee’s preferred future and ask the coachee to visualise a possibility – ‘What would it look like if you were to …?’.

Figure 1.1 Continuum of support and development

Mentoring and coaching should be seen as a continuum in terms of supporting and developing teachers.

This blended approach is often evident when mentoring NQTs. When the NQTs are starting out, it is very much a mentoring relationship. You will be imparting your knowledge and skills to the NQTs, so that they can develop as teachers. As the mentees become more confident and competent, the balance between mentoring and coaching shifts further along the continuum towards coaching.

One other important difference between coaching and mentoring is that of making judgements. Often a mentor has to make a judgement about the standard reached by the person being mentored, for example has he or she met the qualified teacher status (QTS) standards or the induction standards? This will result in quite a different relationship from that between coach and coachee, where it is very important not to be judgemental.

So, what are the skills that make a good coach? It is widely agreed that there are four:

- listening

- asking open questions

- clarifying points

- encouraging reflection.

Examples of these will be discussed later. Coaches also need to be good at:

- building rapport – using posture, gestures, eye contact and so on

- adopting a non-judgemental view of others

- challenging beliefs – a good coach must be willing to have d...