![]()

Section 1

Background to ADHD

![]()

1

The concept of ADHD

This opening chapter in Section 1 provides basic background knowledge of the concept of ADHD by highlighting several important and often controversial areas, beginning with differences in approaches to diagnosis of the disorder. Changes in terminology over time point to varying attitudes regarding the nature of ADHD. There is an examination of the multi-factorial causes as well as the variation in prevalence figures for the disorder. Coexisting social, emotional and educational difficulties often experienced by children with ADHD and the long-term prognosis are discussed. The chapter concludes by looking at medical, educational and social interventions used with individuals with ADHD, as well as listing some alternative and complementary interventions.

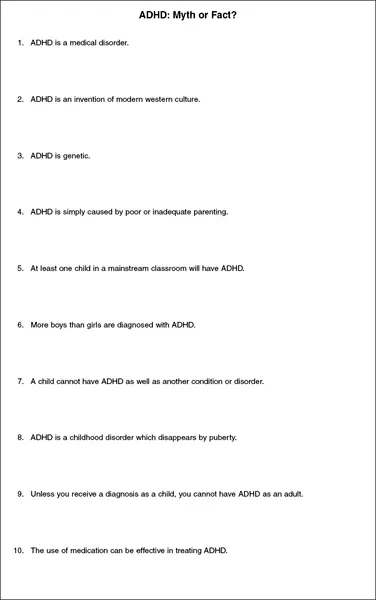

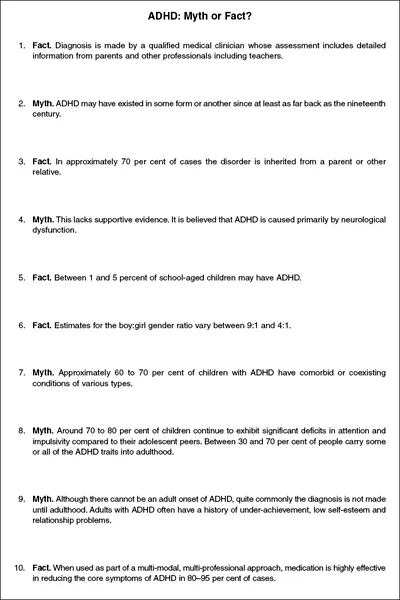

The ‘Myth or Fact?’ sheets (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2, also available as downloadable materials) offer a good starting point for the reader wishing to know more about the background of ADHD. Some of the following subsections are examined in greater detail in subsequent chapters.

Diagnosis

ADHD is a medical disorder and diagnosis is made by a qualified medical clinician (paediatrician or child psychiatrist) using one of two sets of diagnostic criteria currently in use. Traditionally in Europe and the UK the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which refers to ‘hyperkinetic disorder’ (HKD) rather than ADHD, had been the preferred classification system (WHO, 1990). In recent years there has been more use of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) which is widely followed in the USA, Australia and other countries (APA, 2000). In the DSM-IV system the behavioural characteristics associated with ADHD do not represent three primary symptoms but two, with hyperactivity forming a single symptom group with impulsivity. This system is capable of identifying three main subtypes of ADHD (the first subtype is thought to be more common in girls than boys and the other two subtypes are more common in boys than girls):

Figure 1.1 ADHD: Myth or Fact? (Sheet 1)

Figure 1.2 ADHD: Myth or Fact? (Sheet 2)

- the predominantly inattentive type (often known as ADD);

- the predominantly hyperactive–impulsive type;

- the combined type.

The main difference between diagnoses made using ICD-10 criteria and DSM-IV criteria is that ICD-10 focuses on extreme levels of hyperactivity and does not have a non-hyperactive subtype. The differences between the two sets of criteria mean that ICD-10 have been repeatedly shown to select a smaller group of children with more severe symptoms than those selected using DSM-IV. Munden and Arcelus (1999) are among those who advocate the use of DSM-IV criteria: firstly, to identify more children who may have significant impairment but do not satisfy ICD-10 criteria, but who could benefit from treatment and intervention. Secondly, the majority of international research is being carried out on patients who fulfil DSMIV criteria and if UK clinicians wish to utilise evidence from such research they will have to apply it to the same clinical population.

A rigorous assessment is based on the child’s past medical history, educational history, family history, physical examination and information from other professionals, including teachers and educational psychologists. Approaches used include observation of the child, both in the clinic setting and the school environment; in-depth interviews with the child, parents and teachers; aptitude testing and physiological and neurological testing; and the completion of behavioural rating scales. Symptoms emerge more clearly between the ages of 6 and 9 years. Findings from the school survey undertaken as part of the research show that the highest percentage of individuals was diagnosed in the 5–9 year age group. The four target students included in the six case studies who had received formal diagnoses of ADHD by the end of the research period were diagnosed as follows:

- David was diagnosed at the age of 4 years 4 months.

- Edward was diagnosed at the age of approximately 5 years.

- Carl was diagnosed at the age of 6 years 9 months.

- Adam was diagnosed at the age of 8 years 8 months.

History

ADHD may have existed in some form or another since at least as far back as the nineteenth century. One of the first professional reports of the disorder was probably in 1902 in The Lancet by George Still, a British paediatrician.

In the 1930s, behavioural disturbances were related to brain injury and in 1937 stimulant medication (amphetamine) was first used to treat a group of behaviourally disordered children. It was in the 1950s and 1960s that the term ‘minimal brain dysfunction’ was used, with the disorder no longer ascribed to brain damage but focusing more on brain mechanisms. Methylphenidate (Ritalin), introduced in 1957, began to be more widely used, particularly in the USA. During the 1960s the ‘hyperactive child syndrome’ became a popular label. Research in the 1970s suggested that attention and not hyperactivity was the key feature in this disorder and led to the establishment of ‘attention deficit disorder’ (ADD) as a category in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1980. There have since been several reformulations of DSM, with the category of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) first used in 1987 and redefined in 1994, with a further text revision in 2000 (DSM-IV TR) (APA, 2000). The various name changes that the disorder has undergone over the years reflect changing conceptualisations of the nature of the condition.

In Sweden and other Scandinavian countries the term ‘DAMP’ (deficits in attention, motor control and perception) has frequently been used as a diagnosis. DAMP is a combination of ADHD and DCD (developmental coordination disorder, present in 50 per cent of ADHD cases). Sometimes the combined expression ADHD/DAMP is used (Gillberg, 2002).

Causes

Although there is no one single ‘cause’ of ADHD, it is believed that the disorder is caused primarily by neurological dysfunction. Research studies have found particularly low levels of activity in the neurotransmitters in the frontal lobes of the brain which control impulses and regulate the direction of attention. This means that children with ADHD often experience problems in inhibiting or delaying a behavioural response. The causes of this particular brain dysfunction in most cases appear to be genetic, with approximately 70 per cent of cases being inherited. Most children diagnosed with ADHD have a close relative (usually male) affected to some degree by the same problem. In studies of identical twins, both have ADHD in almost 90 per cent of cases, and siblings carry a 30–40 per cent risk of inheriting the disorder. Environmental factors such as brain disease, brain injury or toxin exposure may be the cause of 20–30 per cent of cases (Cooper and Bilton, 2002). Other suggested risk factors for ADHD include pregnancy and delivery complications, prematurity leading to low birth weight and foetal exposure to alcohol and cigarettes.

When seeking to explain the multi-factorial causes of ADHD, reference is often made to the interrelationship between nature and nurture. The concept is described by many as a bio-psycho-social disorder. This means it may be viewed as ‘a problem which has a biological element, but that interacts with psychosocial factors in the individual’s social, cultural and physical environment’ (Cooper, 2006: 255). Biological factors include genetic influences and brain functions, psychological factors include cognitive and emotional processes and social factors include parental child-rearing practices and classroom management (BPS, 2000).

Prevalence

Although figures vary according to where and when studies are carried out and the diagnostic criteria used, it appears that ADHD is present throughout the world. It occurs across social and cultural boundaries and in all ethnic groups. International estimates of prevalence rates vary, and include suggestions of between 3 and 6 per cent of children and young people (Cooper, 2006). American data collected in 2003 suggests prevalence rates of between 5 and 8 per cent in children aged 4 to 17 years old (Goldstein, 2006). One interesting theory put forward for national differences in countries such as North America and Australia is that ‘in past centuries, the more impulsive risk takers were more likely to emigrate or become involved in antisocial activity that would have led to their transportation. This group would probably have had a higher incidence of ADHD, which would have been inherited by subsequent generations’ (Kewley, 2005: 13).

In the UK it is difficult to ascertain accurate national prevalence figures. The breakdown of SEN figures provided in government statistics does not include a discrete category for ADHD. Taylor and Hemsley (1995) suggest that 0.5–1 per cent of children in the UK have ADHD or hyperkinetic disorder (HKD). It was recently reported that there were 4,539 children and young people diagnosed with ADHD known to NHS services in Scotland. This is approximately 0.6 per cent of the school-aged population (NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, 2008). Government guidance for schools in Northern Ireland refers to ADHD occurring in 1–3 per cent of the population (Department of Education, 2005). Figures published by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) state that:

It has been estimated that approximately 1% of school-aged children (about 69,000 6–16 year olds in England and 4,200 in Wales) meet the diagnostic criteria for HKD (i.e. severe combined-type ADHD). The estimated prevalence of all ADHD is considerably higher, around 5% of school-aged children (345,000 in England and 21,000 in Wales). (2000: 3)

On average, this means that in a mainstream class of 30 children it is likely that at least one child will have ADHD. Distribution is not even, with some schools having a disproportionate number of students displaying ADHD-type characteristics. The average local prevalence rate in several local authorities where school surveys have been carried out was found to be approximately 0.5 per cent of each school population (Wheeler, 2007). In 151 out of 256 schools that responded to the ADHD survey there were 413 individuals reported as being formally diagnosed with ADHD. This represents 0.53 per cent of the total school population, i.e. 5.3 students per 1,000. It can be seen in the breakdown by age shown in Figure 1.3 that the highest proportion of diagnosed students was in the 7–11 years age group – this concurs with suggestions that the disorder is considered to be more prevalent in the age range 6–11 years with a reduction in prevalence with socio-emotional maturation.

Estimates of gender differences vary. Boys generally tend to outnumber girls, although there is a possibility of an under-representation of girls in estimated figures. It is believed that boys are more likely to be identified because they are likely to be more overtly aggressive and therefore to be noticed to have difficulties. M...