![]()

Chapter 1

Sustainable leadership

Brent Davies

The emphasis on short-term accountability measures has often prioritized the use of short-term management strategies to meet test and Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) measures. However, the longer-term sustainable development of the school requires leadership that is embedded in a culture focused on moral purpose and the educational success of all students. Moving away from short-termism to more fundamental consideration of sustainable leadership is the focus of this chapter. Sustainable leadership can be considered to be made up of:

the key factors that underpin the longer-term development of the school. It builds a leadership culture based on moral purpose which provides success that is accessible to all.

A useful analogy is that of a tree where the roots (sustainable leadership) underpin all the school’s activities.

While it would be naive or unrealistic to suggest that school leaders do not have to respond to short-term accountability targets and managerial imperatives, it is important that these responses are set against sustainable leadership factors. Just as the fellowship of the nine set out in The Lord of the Rings (Tolkien, 1991: 268) to battle with the forces of Mordor, so I propose nine sustainable leadership factors that should be developed and deployed to battle with the dangers of managerial short-termism! These factors have been drawn from recent research of sustainable and strategically successful schools.

1. Outcomes not just outputs

The importance of deep learning outcomes and not just short-term test outputs is the first underlying principle of sustainable leadership. While test scores in terms of standard assessment tasks (SATs) results and General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) are important indicators, they are just that: indicators. They do not sum up the school or provide a holistic view of where the school is going. The downside of output measures is that schools reorientate their approaches to achieve yet higher and higher results. The danger of this is that education merely becomes an information transmission system that the recipients replicate in test conditions. External testing should provide a floor to standards and not be the ceiling. What is critical is that 16-year-olds enjoy reading, they have a positive view of school, they engage in problem-solving in a creative way with their peers; these are the outcomes of education. These skills are not necessarily measured by GCSE results! What we need is leadership that, while addressing accountability demands, focuses on deep learning and fundamental educational outcomes and values. This often takes courage in an era where the culture of working harder and harder to improve pass rates often ignores the real purpose of education.

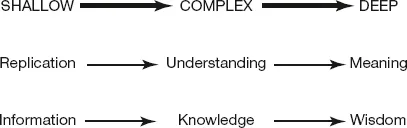

The nature of learning poses a major strategic challenge to schools because of the attributes of short-term accountability and standards frameworks. If we were to think of learning moving from shallow learning to complex learning and then to deep learning we could characterize this as in Figure 1.1:

Figure 1.1 Deep learning

The challenge for schools is that the short-term accountability demands tend to require the replication of information with some attributes of complex learning, but assess little of the learning on the complex to deep end of the spectrum. Deep learning requires that we develop in children both the love of learning itself and some understanding of the meaning of complex knowledge so that they can exercise wisdom to make informed choices in their lives. I would argue that high-level outputs can be achieved by deep learning and the outcomes associated with it. However, it has to be a conscious choice by leaders to develop sustainable learning approaches.

In essence, sustainable leadership is inextricably linked to deep learning. It is the framework that allows deep learning to develop. It has at its core a set of beliefs about learning allied to personal and professional courage that allows those beliefs to be implemented and flourish. The slavish response to short-term demands can destroy the ability to build long-term capacity. A balance has to be struck where deep learning structures and approaches are developed that can deliver measurable outputs but those outputs are seen as indicators of deeper learning and abilities and not as ends in themselves. Sustainable leadership sets as its target the building of a culture of learning in the school that establishes a framework that can move the child’s understanding from the shallow through the complex to deep learning.

2. Balancing short- and long-term objectives

There is an assumption that strategy is about the long term and is incompatible with short-term objectives. This, I believe, is inappropriate for a number of reasons. The situation should not be seen as an either/or position. It is of little value trying to convince parents that this year their child has not learnt to read but that ‘we have plans in place that may remedy the situation in the next year or two’. Most children’s experience is short term in relation to what they do this week, this month or what they achieve this year, and which class they are in next year. Success in the short term is an important factor in their lives, as is success in the long term.

There are some basic things that an education system should provide for children. It should provide them with definable learning achievements that allow them to function and prosper in society. Where children are not making the progress we expected for them, they need extra support and educational input to help them realize their potential. This, by necessity, requires regular review against benchmarks. Thus Hargreaves and Fink’s disdain for ‘imposed short-term achievement targets’ (2006: 253) is difficult to support. However, I recognize the danger of seeing short-term benchmarks as the outcomes and not indicators of progress. Indeed, if annual tests were seen as diagnostic and generated learning plans for children rather than outcome scores for schools, the problem of testing may be solved overnight. What needs to be done is that the short term should not be seen as separate from the long term or as being in conflict with it, but as part of a holistic framework where short-term assessments are seen to guides on the long-term journey.

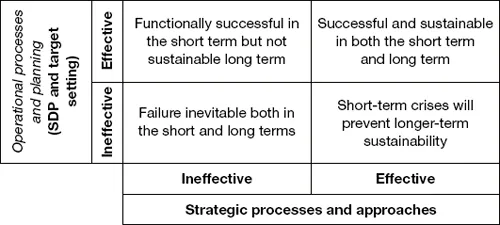

This balanced view of the short-term and long-term perspective was shown in Figure 1.1. It is of little use having a long-term strategic plan if it ignores the short term, as we see in Figure 1.2. The result in the bottom-right quadrant will be that short-term crises will prevent the long term ever being achieved. Similarly, merely operating on a short-term perspective, the top-left quadrant, will prevent long-term sustainability ever being achieved. What is needed is a balance between the short and long term as witnessed in the quadrant at the top right.

Figure 1.2 Short-term viability and long-term sustainability (based on Davies, B.J., 2004)

The challenge for headteachers is to be both leaders and managers. Vision that cannot be translated into action has no impact. Similarly, continuing to manage the now without change and development is not building capacity for the future. We need to balance both the long-and the short-term approaches. Derek Wise, headteacher of Cramlington High School, has a delightful expression, describing himself as ‘pragmatopian’. By this he means that he has his head in the clouds to see the future (utopian) but is pragmatic enough to have his feet on the ground to make sure everything is working in the short term. This balancing of the short term and the long term is a key factor in a sustainable leadership approach.

3. Processes not plans

Why is the idea of process so important? John Novak from Canada, in his work on invitational leadership (Novak, 2002), contrasts the ‘done with’ approach to the ‘done to’ approach which often leaves the staff ‘done in’. The reason that strategically focused schools spend a great deal of time and effort on processes to involve staff is that involvement:

- allows a wider range of talented people to contribute;

- draws on expertise and experience;

- builds consensus and agreement;

- builds transparency and understanding;

- articulates challenges and invites solutions.

Schools are living systems made up of people who can choose to contribute or not contribute, or choose to be positive to change or negative to change. Which choices they take can be influenced by the strategic leaders in the school. Strategic change takes time and effort, and leaders often report to me that they underestimate the time and effort needed. The approach should be to work with the ‘willing’ to start the strategic conversations, build ideas and visions, and then slowly draw the reluctant members on the staff to join in. Schools are a network of individuals linked together through a series of interconnections largely based on conversation. This is powerfully illustrated by Van der Heijden (1996: 273): ‘Often much more important is the informal learning activity consisting of unscheduled discussions, debate and conversation about strategic questions that goes on continuously at all levels in the organisation.’

What is required to create an effective individual and institutional conversation? The first way is for leaders to model behaviour. How do they interact with colleagues on a day-to-day basis? Do they just react to the current demands or do they engage people in thinking and talking about the future? Leaders need to take the informal opportunities to interact with others both to discuss the problems of the present, but also to engage in a dialogue about the challenges of the future. The conversation over coffee or walking to the car park can be just as important as more formal meetings. It is also necessary to work with other leaders in the school to encourage them to do likewise so that the culture in the school builds reflection and dialogue.

How we structure meetings has a critical impact on the ability to engage in strategic conversations. When I meet successful leaders in the course of my research, I find that their schools separate out strategic and operational matters, and that they structure separate meetings to deal with those items. This gives the formal forum to deal with discussions and conversations to run alongside the informal discussions. Davies (2006) talks about articulating a vision and engaging in conversations with colleagues, as a means to build participation and motivation to enhance strategic capacity in the school. The critical test of strategy is to ask a teacher what they are doing in their classroom this week that has been driven by the school plan. If they cannot articulate a view then it is likely that the plan is on a shelf in the headteacher’s office and used only for external evaluation. What should happen is that, because they have been part of the process, staff can articulate the four or five major development themes of the school.

4. Passion

Passion is often seen in terms of a passion for social justice, passion for learning, passion to make a difference. It is the passion to make a difference that turns beliefs into reality and is the mark of sustainable leadership. Beliefs are statements or views that help us set our personal views and experiences into context. My own passion for education would be based on the fact that:

- I believe every child can achieve;

- I believe every child will achieve;

- I believe that all children are entitled to high quality education;

- I believe that we collectively and individually can make a difference to children’s learning.

Passion works on the emotional side of leadership. Bolman and Deal (1995: 12), in their inspirational book Leading with Soul emphasize the emotional side of leadership: ‘Heart, hope and faith, rooted in soul and spirit, are necessary for today’s managers to become tomorrow’s leaders, for today’s sterile bureaucracies to become tomorrow’s communities of meaning’.

Passion must be the driving force that moves vision into action. Bennis and Nanus (1985: 92–3) argue that the creation of a sense of meaning is one of the distinguishing features of leadership:

the leader operates on the emotional and spiritual resources of the organisation, on its values, commitment, and aspirations … Leaders often inspire their followers to high levels of achievement by showing them how their work contributes to worthwhile ends. It is an emotional appeal to some of the most fundamental of human needs – the need to be important, to make a difference, to feel useful, to be part of a successful and worthwhile enterprise.

Sustainable leadership establishes a set of values and purposes that underpin the educational process in the school. Most significantly it is the individual passion and commitment of the leader that drives the values and purposes into reality. Values without implementation do little for the school. It is in the tackling of difficult challenges to change and improve, often by confronting unacceptable practices, that passionate leaders show their educational values.

What skills does sustainable leadership require to translate passion into reality? Deal and Peterson (1999: 87) see that school leaders take on eight major symbolic roles:

- Historian – understanding where the school has come from and why it behaves currently as it does.

- Anthropological sleuth – seeks to understand the current set of norms, values and beliefs that define the current culture.

- Visionary – works with others to define a deeply value-focused picture of the future for the school.

- Symbolic – affirms values through dr...