![]()

| 1 | CHILD SOCIAL WORK POLICY & PRACTICE

An Introduction |

CHILD SOCIALWORK, STATE AND FAMILY

In principle, the UK’s framework for child welfare is fairly straightforward. The dominant assumption is that the upbringing of children is largely a matter for parents or guardians. In turn, the state’s role is threefold. First, it sets the legal parameters for parental rights and responsibilities. Second, it offers support to families in areas such as health care, education, housing or cash benefits, either ‘universally’ to all families or more ‘selectively’, based on criteria of deprivation or ‘special needs’. Third, the state has evolved powers and duties to ‘intervene’ in families when there are concerns regarding child welfare, and it is broadly with this role that our focus rests.

This framework, however, hides great complexity. In the political and ideological arena, there are struggles over the nature and level of service provision to families and frequently over whether the state should have greater or lesser powers of intervention in its protective role. Arguably the central tension is between philosophies of ‘child rescue’ and ‘family support’. In the former, greater emphasis is placed on the individuality of the child, their vulnerability to abuse and the appropriateness of removal from the family in such circumstances. In the latter, the unity and caring qualities of families are emphasised, with child welfare to be secured primarily through better support to parents. It is also important to recognise that the ‘state’ comprises a complex apparatus – with a separation between government and judiciary, divisions of responsibility between government departments (including devolved institutions within the UK) and the delivery of services through local authorities, private and voluntary organisations. Unsurprisingly, this complexity, allied to frequent reorganisations, gives rise to inconsistencies and contradictions in policy and practice, and an ongoing quest for effective co-ordination. Meanwhile, on the front line, individual workers are faced with difficult and far-reaching decisions regarding the adequacy of parenting and how to address perceived risks to children’s safety and development.

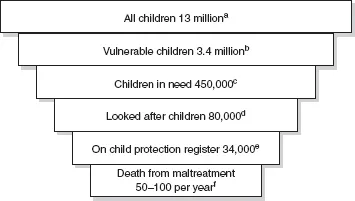

Figure 1.1 Children’s involvement with social care services – a statistical overview

Source:

aOffice for National Statistics (2005) Key Population and Vital Statistics Local and Health Authority Areas. London: ONS;

bPalmer, G., Maclnnes, T. and Kenway, P. (2006) Monitoring Poverty and Social Exclusion 2006. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation;

cExtrapolated for UK from English data (DfES 2006a);

dFigures accessed from www.haaf.org.uk/info/stats/index.shtml;

eFigures collated from www.nspcc.org.uk/Inform/statitics;

fExtrapolated from Creighton, S. and Tissier, G. (2003) Child Killings in England and Wales. London: NSPCC.

In subsequent chapters, more detailed statistics will be reported on a range of issues, but at this point, a few headline figures may serve to convey an initial sense of the scale and scope of child social care. Figure 1.1 presents these statistics in the context of broader child populations and thus introduces the notion of ‘filters’ prior to, and following contact with, social care services.

The category of vulnerable children is based on child poverty using the widely accepted benchmark of living in a household below 60 per cent median income. The Children Act 1989 section (hereafter s) 17 defines a child as ‘in need’ if any of the following conditions apply, namely:

| (a) | he is unlikely to achieve or maintain, or to have the opportunity of achieving or maintaining, a reasonable standard of health or development without the provision for him of services by a local authority; |

| (b) | his health or development is likely to be significantly impaired, or further impaired, without the provision for him of such services; or |

| (c) | he is disabled. |

Being deemed a child in need represents the gateway to receiving ‘family support’ services, which will be analysed in Chapter 3. As can be seen from Figure 1.1, the number of children in need represents approximately one in eight vulnerable children. Most, though not all, children in need come from families living below the poverty line, and the relationship between poverty and child welfare concerns will be discussed later in the book. The term ‘looked after’ was also introduced in the Children Act, replacing the term ‘in care’. It encompasses all those being looked after by local authorities, whether on a voluntary basis or following a court order (or a supervision requirement in Scotland). Figure 1.1 shows that the number of ‘looked after’ children at any one time is roughly one-sixth of the children-in-need population and under 1 per cent of all children. Children, a minority of whom may be looked after children, are placed on the child protection register when they are regarded as at risk of significant harm (see Chapter 4).

These statistics are open to different interpretations. On the one hand, they show that only a minority of children are likely to have direct contact with child social care services, although more will do so during their lifetimes than these snapshot figures suggest. On the other, in raw terms, these numbers are substantial while their links with poverty and deprivation raise important issues of social justice. In addition, state child welfare services cast a long shadow in terms of public perception and fears.

In 2006–2007, expenditure on children’s services accounted for £5 billion, 25 per cent of the social care budget and approximately 0.4 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (Information Centre, 2008). The children’s social care workforce in England has been estimated at 127,000 (including foster carers), with roughly four-fifths working for local authorities and the remainder in the private and voluntary sectors (Department for Education and Skills (DfES), 2005a).

CHILD SOCIAL WORK AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Changing childhood(s)

Clearly, child social work policy and practice do not operate in a vacuum, but in particular social and historical contexts. In this section, we offer a review of recent developments and debates in thinking about childhood. Over the past two decades or so, sociological analysis has been increasingly influential in promoting awareness of the ways in which childhood is ‘socially constructed’ (Jenks, 1996). This viewpoint is critical of perspectives that construe childhood simply in terms of physical maturation, ‘stages’ of psychological development or passive socialisation. James et al. (1998) emphasise the need to see children as ‘beings’ (the fully fledged social actors they are in the present) rather than as ‘becomings’ (the adults they may be in the future).

Following Aries’s pioneering (1962) work, the most powerful evidence for the social constructionist view stems from wide historical and cross-cultural variations found in ideas and practice relating to childhood, which refute notions that it represents a ‘natural state’ (Kehily, 2004). Writers such as Lee (2001) and Hendrick (2003) have mapped the rise in western societies of childhood as a progressively extended period of preparation for adulthood built around compulsory schooling and removal from the world of work. From the early nineteenth century onwards, the state took an increasing role in managing its populations, with children particular targets for intervention. Ideas of childhood ‘innocence’ were central to this endeavour, whether this was seen as the natural state of children (‘little angels’) or the product of hard-fought battle against their innate sinfulness (‘little devils’) (Jenks, 1996).

In recent times, there has been significant debate on the state of childhood – variously described as ‘disappearing’ (Postman, 1982), in ‘crisis’ (Scraton, 1997) or ‘toxic’ (Palmer, 2006). Ideas of lost innocence are central to these debates. This may be in relation to the perceived loss of a more carefree life for children due to parental fears and a risk avoidant culture, or the way in which protective confinement in homes saturated by the electronic media has brought about greater exposure to the ‘adult’ world, its secrets and painful issues. For critics, the loss of innocence has inexorably led to increases in both troubling (e.g. crime, drug abuse, sexual activity) and troubled (e.g. self-harm, eating disorders) behaviour among children and young people. While claims of the ‘death of childhood’ are somewhat exaggerated (Buckingham, 2000), there is widespread acceptance that today’s children ‘grow up more quickly’ in many respects than previous generations, although some commentators welcome what they see as children’s more ‘savvy’ approach to consumption, the media or social issues (Kenway and Bullen, 2001).

Although these debates may seem somewhat ‘academic’, they are relevant to child care policy and practice in a number of ways. First, judgements regarding children’s developmental needs, whether they are suffering harm as a result of maltreatment, and what represents their ‘best interests’, are inextricably bound up with normative views of childhood. Social constructionist perspectives alert us both to the changing and contested nature of such norms and their complex relationship to variables such as social class, gender, ethnicity, disability and sexuality. Second, constructions of childhood are equally salient for looked after children and the care to be provided by the state. Third, awareness of social construction can also encourage a questioning approach to the seeming ‘hard evidence’ gleaned from developmental measurement, psychological testing and tendencies to medicalise behaviours deemed to be problematic. However, as Fawcett et al. (2004) argue, it is important not to be dismissive of the biological and psychological domains and to avoid the relativistic view of phenomena as ‘only constructions’. Finally, the social constructionist emphasis on children’s agency is supportive of promoting their ‘voice’ and participation within social care services.

Changing families, changing parenting

As noted earlier, the seemingly straightforward framework for relationships between the state and the family hides great complexity. At the level of government policy, this reflects both political ideology and changing economic and social conditions. The New Labour government has identified the family as ‘at the heart of our society’ due to its provision of love, support, education and moral guidance, a means of promoting economic prosperity while ameliorating a range of social problems linked to social exclusion and deviant behaviour (Home Office, 1998). However, in a period of rapid social change, the family has been increasingly cast as vulnerable due to economic pressures, breakdown through divorce and for many, the effects of poverty, crime and drug misuse.

The context for such concerns developed in the closing decades of the twentieth century, which witnessed significant changes among families in the UK, prompting debates that mirror in many respects those relating to the changes in childhood described above (Barrett, 2004). The broad contours of change are well known and concisely captured in Social Trends 2007 (Self and Zealey, 2007). Marriages declined from 480,300 in 1972 to 283,700 in 2005, while divorces rose from around 50,0000 in the late 1960s to 155,00 in 2005. Lone-parent families have risen from 7 per cent of those with dependent children in 1972, to 24 per cent in 2006. Rising cohabitation meant that the percentage of children born outside of marriage increased from 12 to 43 per cent between 1980 and 2005. Self and Zealey (2007) also report significantly later marriage and first-time childbirth since the 1970s.

Crucially, these changes coincided with greater female participation in the labour market. Employment rates among women of working age rose from 56 per cent in 1971 to 70 per cent in 2005 (Self and Zealey, 2007) This included significant rises in both full- and part-time work, although the one-and-a-half-earner household is closer to the norm in two-parent families (Lister, 2006). It must be noted, of course, that these broad trends in family structure, formation and employment mask significant differences based on socio-economic status, ethnicity and religion (Berthoud, 2007).

Such family changes have been the subject of fierce controversy and ideological conflict. For conservative traditionalists, these and other developments (such as recognition of same-sex partnerships) signify the demise of the family as a stabilising social force. Significant blame for this is attached to feminism and a wider ‘rights culture’ for encouraging women to forsake the homemaker role, with family relationships and parenthood reduced to a ‘lifestyle choice’ (Davies, 1993). Many of these themes coalesce in conservative analysis of the ‘underclass’, where lone mothers stand accused of welfare dependency, rearing their children without appropriate (male) role models and fuelling crime and anti-social behaviour (Murray, 1990).

For the centre-left, such changes have evoked a more mixed response, with recognition of the damaging effects of family instability on children but support for changes in gender roles and greater opportunities for women. Recent family changes are broadly interpreted as promoting adult relationships based on intimacy and self-fulfilment and more ‘democratic’ relationships between parents and children (Giddens, 1992; Beck, 1997). Critical perspectives on the family are also seen as promoting awareness of problems such as domestic violence and intra-familial child maltreatment. Overall, the centre-left tends to embrace a more pluralistic view of family forms.

Drawing on Etzioni’s (1993) concept of ‘parenting deficit’ as a major contributing factor to social problems, the New Labour government has considerably increased intervention in relation to parenting, with an uneasy amalgam of the supportive and punitive (Henricson, 2003). Thus, more generous tax credits and...