- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

We experience violence all our lives, from that very first scream of birth. It has been industrialized and domesticated. Our culture has not become totally accustomed to violence, but accustomed enough. Perhaps more than enough.

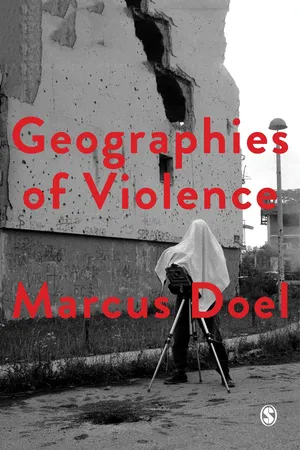

Geographies of Violence is a critical human geography of the history of violence, from Ancient Rome and Enlightened wars through to natural disasters, animal slaughter, and genocide. Written with incredible insight and flair, this is a thought-provoking text for human geography students and researchers alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geographies of Violence by Marcus Doel,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Best of All Possible Violence The Frightful Fallout from the Great Lisbon Earthquake

The true Evil is the very gaze which sees evil all around itself.Hegel, quoted in Žižek, Santner and Reinhard, 2005: 139

Our taste for violence is as ardent as ever. My fondest example is a housewife recalling her first use of a food processor. ‘Crushing food with lightning rapidity seems brutal and shocking’, she recalls. ‘I see hard nuts, apples, lemon peel cut to pieces and transformed into an unrecognizable mass. … Something inside me rebels against this bringing of food into line’ (quoted in Wildt, 1995: 31). Her distaste for the miniature slaughterhouse placed at her disposal is palpable. And yet, she continues, ‘once I had tried it out a few times my hostility changed to honest admiration’.

Although unleashing ferocious violence on innocent vegetables is hardly a moral outrage, it nicely illustrates how violence has been industrialized and domesticated: from the ritual cruelty shared between lovers (teasing, taunting, belittling) to the calculated exploitation of mass-murder machines. Our culture has not become accustomed to all violence, to be sure; but enough violence, nonetheless: more than enough, perhaps. For just as millions of tabletop slaughterhouses rip through the flesh of soft fruit, millions of financial transactions tear through the fabric of the world: everything from deforestation and strip mining to ghost cities and suburban sprawl (Ewing, 2016; Leslie, 2013). Neighbourhoods, conurbations, and landscapes are shredded by capitalist development in an ever-intensifying maelstrom of violence: ‘from its relentless and insatiable pressure for growth and progress; … its pitiless destruction of everything and everyone it cannot use … and its capacity to exploit crisis and chaos as a springboard for still more development, to feed itself on its own self-destruction’ (Berman, 1999: 138–9). Capitalism is a carnival of cannibalism (Baudrillard, 2010b), some of which is spectacularly dramatized, especially in times of ‘crisis’, but most of which takes the form of an ‘attritional lethality’ (Nixon, 2011) that nibbles away at the face of the Earth – as if the planet itself had been taken to Room 101 in the Ministry of Love (Orwell, 2000). ‘Landscapes could be classified in terms of how easily they can be nibbled, BITTEN’, suggests Lyotard (1989a: 214). Walter Benjamin (1985) famously drew inspiration from Paul Klee’s painting, Angelus Novus (1920), to convey this nightmarish storm of gnawing violence:

Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to … make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise. … This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress. (Benjamin, 1985: 257–8)

Before entering the slaughterhouses of modernity and the ruins of capitalist development, I want to consider another key instance of divine violence: the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, which shook Europe’s newly acquired spirit of philosophical optimism (that all was for the best) and its renewed confidence in human reason (daring to know), leaving ‘those who lived through it feeling conceptually devastated’ (Neiman, 2004: 239). We remain subject to the aftershocks of a shattered optimism and a wrecked Enlightenment, aftershocks that continue to reverberate around the world.

Optimism – in the sense of the optimal, the best possible, rather than the merely ‘hopeful’, which, once soured, becomes ‘cruel optimism’ (Berlant, 2011) – sought to explain how a thoroughly good, all-knowing, and all-powerful God could allow evil to flourish in His world, and the explanation boiled down to an optimal calculation that only a divinity could make: not simply that the occurrence of evil contributes to the greater good (sacrifice and silver linings), but rather that these specific evils are necessary for the greatest possible good to occur (optimization). God chose these evils because they are the best evils for His world. For an optimist, then, whatever happens is not only an integral part of a ‘divine plan’, it is essential to the unfolding of ‘the best possible world’. Disease, war, famine, and suchlike all turn out to have been for the best. Similarly, with storms, floods, droughts, and so on. What was so shocking about the Lisbon earthquake, however, was that it demolished one of the most religious and modern cities on Earth. Indeed, the Lisbon of 1755 was a powerful imperial city in the grip of a construction boom. In the reign of King João V (1706–50), around 500 tons of gold had been brought to Lisbon from Portugal’s most lucrative colony, Brazil, along with other plundered riches, including diamonds, sugar, tobacco, coffee, and slaves. ‘“Riches do not profit in the day of wrath,” warned Proverbs, and on All Saints’ 1755 they didn’t’, comments Nicholas Shrady (2009: 111), ‘like a biblical day of reckoning, most of what the city and its inhabitants had coveted was reduced to rubble’. At least 60,000 people were killed, and 12,000 buildings destroyed, by the earthquake, tsunami, and wildfires. Such devastation shocked God-fearing folk, not least because ‘one in six of Lisbon’s adult population was a religioso’, notes Edward Paice (2008: 10). ‘With more than 500 monasteries and convents and countless churches, the Portugal of this era came to be memorably described as “more priest-ridden than any other country in the world, with the possible exception of Tibet”’ (Paice, 2008: 10, quoting Charles Davison, 1936). Whether this ‘urbicide’ expressed God’s wrath or the optimal unfolding of the world, people feared what lay in store for other, less pious, places.

The Lisbon of 1755 was on the cutting edge of modernity. Like many other European cities, Lisbon became a repository for extraordinary wealth plundered from a worldwide empire. The suffering of millions of distant others was transmogrified into monumental architecture and lavish interiors. And yet Lisbon remained in the grip of monarchy and church, whose despotic tendencies were a fetter on the Enlightenment spirit of entrusting human reason with the power to take command of the brave new world of modernity. The Portuguese Inquisition, established in 1536 by Pope Paul III at the request of King João III, was still combating heresy in the 1750s through ‘torture, show trials, and ghastly public autos-da-fé’ (Shrady, 2009: 89) – those ritual ‘acts of faith’ by way of which evildoers performed public penance through suffering, such as being flayed, hung or burnt at the stake; acts that could even seize the dead. For example, ‘the execution of suicides … was usually done by dragging their corpses through the street’ (Friedland, 2012: 188). Secular versions of the auto-da-fé continued well beyond the eighteenth century, not least in the form of public executions and exemplary punishments; although with the death of God, and the abandonment of Man to the ‘here and now’, at least the dead were spared the indignity of postmortem execution as their souls were cast beyond the reach of power. Death no longer necessarily signified the transition from one authority to another (from an earthly sovereign to a Heavenly Father), but rather ‘the moment when the individual escapes all power, falls back on himself and retreats … into his own privacy’ (Foucault, 2004: 248). Nevertheless, cadavers would continue to be exploited for all manner of purposes, from dissection to crash tests (Roach, 2004).

Lisbon, then, was a Janus-faced city in 1755, and optimism bridged the gulf between faith and reason. The city glanced forward to the blossoming of modernity by gingerly ‘daring to know’ (as Immanuel Kant belatedly put it when answering the question ‘What is Enlightenment?’ in 1784), thereby risking the wrath of God for usurping His prerogative; whilst also harking back to the foundations of the monarchy and church that still had to be secured at all costs: faith, devotion, and servitude to God and His representatives on Earth, enforced through the law-preserving violence of the Inquisition, and the long-standing institutions of a ‘persecuting society’ originally designed to control heretics, lepers, and Jews (Moore, 1990). Trying to reconcile faith with reason was always a risky undertaking, and the Inquisition was well versed in the suppression of such heresy: from idiosyncratic ravings to rival doctrines. Even proving the necessity of God by way of doubt was to put Him on trial. Indeed, the seventeenth century’s toying with ‘doubt’ (which offered a foretaste of ‘critical’ and ‘revolutionary’ thinking), exemplified by René Descartes, would lead Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to declare in their Communist Manifesto (1848): ‘All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life.’ Accordingly, empowering human reason, daring to know, and raising doubt all flirted with heresy and invited the wrath of God and the state. Enlightenment thinking was primarily a clandestine and scurrilous affair in the eighteenth century, doggedly pursued by the police and censors. The iconic ‘Light of Reason’ tended to illuminate not the upper echelons of society (enlightening despotism from above), but the filth of ‘Grub Street’, often in the guise of pornography and slander (Darnton, 1996).

Faith and reason have always been blood-soaked terms, and would become even more so in the ‘Age of Revolution’ (1789–1848) and the ‘Age of Empire’ (1875–1914), to use Eric Hobsbawm’s (1962, 1994) periodization. The enlightened doctrine of optimism (from the Latin ‘optimum’, meaning ‘best’), which was most famously associated with Leibniz’s (1985) claim in 1710 that God had created ‘the best of all possible worlds’, sought to reconcile faith and reason. For Leibniz, there was no contradiction between the notion that God is omnibenevolent, omnipotent, and omniscient, and the fact that suffering, misfortune, and evil exist in His world. God has chosen this world precisely because it is the best of all possible worlds. This combination of good and evil is optimal, and each instance of minimalist evil contributes to the greater good. Accordingly, what we regard as inexplicable suffering, misfortune, or evil from our all-too-human perspective is necessary for the realization of all that is good. Optimism is essentially a philosophy of silver linings in which ‘evil is a rational manifestation of God’s grandeur and forms a requisite part in the most complex fulfillment of a providential plan’ (Yolton et al., 1995: 382).

Optimism was the perfect mentality for Janus-faced Lisbon, with its ‘embarrassment of riches’ garnered from landscapes of horror on the one hand and its pious devotion to church and state on the other hand. ‘Armed with a portentous faith and a treasury swollen with Brazilian gold’, writes Shrady (2009: 107), King João V ‘went on a building frenzy for the glory of God and his own majesty’, the most lavish part of which was a vast monastery-cum-palace at Mafra. From 1715 to 1735, the project occupied 50,000 workers, ‘had nearly a thousand rooms, from gilt-filled royal chambers to spartan monks’ cells’, and cost an astronomical figure (£4 million), entirely ‘financed by the infernal, slave-driven mines of Brazil’ (Shrady, 2009: 108). And then, on All Saints’ Day 1755, an earthquake laid the priest-ridden and slave-driven city of Lisbon to waste. ‘By the time the first English refugees returned home religious shock-waves generated by the earthquake had spread throughout the northern hemisphere’, contends Edward Paice (2008: 163). Religious and scientific orthodoxy obviously agreed that God spoke through ‘natural’ disasters. While ‘the role of science was to ascertain the exact means by which his speech had been articulated’ (Paice, 2008: 216), the role of religion was to interpret God’s speech: ‘what was His message? And to whom exactly was it addressed?’ (Paice, 2008: 164).

Many Protestants averse to Catholicism, such as the Methodist preacher John Wesley, insisted that God’s wrath was directed at the barbaric Inquisitions of Spain, Portugal, and Rome. By contrast, the Catholic Church attributed the disaster to the sinfulness of the people, even though ‘many people were killed as they crowded into their churches’ while the red-light district emerged largely unscathed (O’Hara, 2010: 38) and ‘hundreds of criminals … made their escape from the fallen prisons’ (Hamblyn, 2009: 44). Despite the ruination of much of Lisbon’s inquisitorial infrastructure – including the Palace of the Inquisition itself, two of its prisons, and its torture chambers – the Catholic Church concluded that it needed to be more, rather than less, zealous in its persecution of heretics, a response that Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) satirized in his best-selling underground novella, Candide, or Optimism: ‘After the earthquake, which had destroyed three-quarters of Lisbon, the sages of that country could think of no more effective means of averting further destruction than to give the people a fine auto-da-fé’ (Voltaire, 2005: 15). Candide was published in 1759 – in the midst of the Seven Years War (1756–63), which was the last major conflict involving all of the great European powers prior to the French Revolution (1789). It was also published under a pseudonym (Dr Ralph), and as a faux translation (ostensibly from German), to misdirect the religious and secular authorities. (Arouet had adopted the nom de plume Voltaire in 1718, after a spell in the Bastille for composing satirical verses that defamed the Duke of Orléans, Regent of France.)

If the disaster was occasioned by the vices of Lisbon’s population, then what did God have in store for rapacious London and debauched Paris? As a precaution, King George II decreed 6 February 1756 as a day of fasting and penance throughout Britain. After all, even the French were ‘shocked by “the extraordinary licentiousness that reigns openly in London”’ (White, 2012: 347). But not every monarch was so god-fearing and credulous. The court of King Louis XV at Versailles ‘seems to have regarded the disaster as a source of morbid amusement’ (Shrady, 2009: 46). Jittery Britain also offered unprecedented aid, sending six ships laden with food, construction materials, and gold and silver coins. Meanwhile, Spain sent four wagonloads of gold coins, and Hamburg sent four shiploads of timber and clothing. Richard Hamblyn (2009: xviii) considers the Lisbon quake to have been ‘the first modern disaster, establishing the protocols of international humanitarian response’, while Shrady attributes this newfound generosity to the growing interdependencies of the European powers. Eighteenth-century Europe was already binding itself into one incestuous world, and Lisbon was its third busiest port.

While Europe was fixated on the meaning of the Lisbon earthquake, it remained oblivious to the devastation of other places, including Albufeira, Cádis, Cascais, Faro, Lagos, Sanlúcar, and Setúbal, and had been largely indifferent to other destructive quakes, such as Lima in 1746, and Port au Prince in 1751. Indeed, Lisbon itself had endured many earthquakes, ‘including severe ones in 1597, 1598, 1699 and 1724’ (Hamblyn, 2009: 12). As always, some people and places are presumed to matter to all, while others count for next to nothing. The suffering of the latter does not yield grievable lives, says Judith Butler (2004, 2009). Such is the intertwined ‘asymmetry of suffering’ and ‘asymmetry of compassion’ (Klein, 2002: 166 and 168, respectively) that reveals the existence of not one but two worlds (at least), despite all of the guff about globalization, the global village, and one-worldism. The world as such ‘does not really exist’, insists Alain Badiou (2008: 60). ‘What exists is a false and closed world, artificially kept separate from general humanity by incessant violence.’ This is why the Occident’s encounter with the New World was so terrifying and diabolical – not only for those Amerindians exterminated and enslaved in their millions, and the millions of Africans subsequently swept up by the transatlantic slave trade to feed the sugar, tobacco, and cotton plantations’ insatiable demand for labour, but also for those god-fearing Europeans who came face to face with the material existence of what should have remained void. It is also why Arizona’s Sonoran Desert (which braces the US–Mexico border) and the Mediterranean Sea (buttressing Europe against incursions from North Africa and the Middle East) have become key sites for the enforcement of lethal border control in the twenty-first century. Thousands have died in these and similar deathscapes, through drowning, dehydration, hypothermia, etc. (De León, 2015; IOM, 2014; Rubio-Goldsmith et al., 2016). The death marches and death voyages have continued, under policies with poetic names such as Prevention Through Deterrence (est. 1994), the US Border Patrol’s on-going strategy, which has ‘pushed unauthorized migration away from population centers and funneled it into more remote and hazardous border regions. This policy has had the unintended consequence of increasing the number of fatalities along the border, as unauthorized migrants attempt to cross over the inhospitable Arizona desert’ (Haddal, 2010: 13–14). The optimization of such policies has made them more lethal, precipitating efforts to ameliorate the suffering, such as the US Border Safety Initiative (with its water stations, panic poles, and rescue teams for ‘distressed aliens’), Italy’s short-lived ‘Operation Mare Nostrum’, the European Union’s (EU) Frontex-led ‘Operation Triton’ (named after the Greek God who weaponized the oceans), and the European Border Surveillance System (Eurosur), all of which deliver militarized humanitarianism and humane militarism. Behind the veil of optimism, which spares the blushes of good people the world over, lies a wasteland where all of the residual evils are dumped.

The screening off from one another of the interconnected worlds of slave-driven colonial horror on the one hand and priest-ridden metropolitan civility on the other is exemplified by the ‘rubber terror’ of the Congo Free State under King Leopold II of Belgium, a century or so after the Lisbon quake. In the late 1890s, Edmund Morel worked for a Liverpool-based shipping company that carried all cargo to and from the Free State via Antwerp. While vessels filled with valuable commodities (mainly rubber and ivory) came out of the Congo, they returned laden with military supplies, steamer parts, and little else. ‘From what he saw at the wharf in Antwerp, and from studying his company’s records in Liverpool, [Morel] deduced the existence – on another continent, thousands of miles away – of slavery’ (Hochschild, 2006: 180). Between 1880 and 1920, as many as 10 million Congolese were murdered, worked to death, starved to death, or died from disease as Leopold’s Congo became the most lucrative colony in Africa. Moreover, since the Congo was the king’s personal property, it was not an affair of state (and therefore not subject to public scrutiny), but an investment vehicle for various companies (such as the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber and Exploration Co., and Société Anversoise du Commerce au Congo), backed by a mercenary gendarmerie (Force Publique), whose brutality became legendary once the veil of commercial secrecy was lifted by Morel (Hochschild, 2006). Like the ‘Honourable East India Company’ – a British joint-stock company backed by Royal Charter (1600) and vast private armies that effectively ruled India for 100 years (from the 1757 Battle of Plassey to the 1857 Indian Rebellion, after which the Crown assumed direct control of India), and which, once China had been broken open during the ‘Opium Wars’ (1839–42, and 1856–60), controlled half of the world’s trade (Milligan, 1995; Robins, 2012) – the Congo Free State was a proving ground for regimes of optimal horror more commonly associated with totalitarianism and the mercenary armies of disaster capitalism’s increasingly lucrative ‘war on terror’ (Scahill, 2008; Singer, 2008).

The screening off from view of the ‘Congo Holocaust’ was so effective that Leopold came to be seen as a great humanitarian for the vast expenditure this ‘Builder King’ lavished on the ‘good people’ of Belgium: parks, museums, galleries, and palaces. Meanwhile, Jeremy Black (2011: 226) wryly notes that Leopold’s form of ‘colonialism involved a degree of control that, while not slavery, was scarcely freedom’. Thereafter, the adventure of capitalism experimented with countless ways of enforcing ‘slavery by another name’, as Douglas Blackmon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- The Joy of Killing

- 1 The Best of All Possible Violence The Frightful Fallout from the Great Lisbon Earthquake

- 2 Once Upon a Time, Long, Long Ago The Cesspits of the Enlightenment

- 3 Pre-industrial Mass Killing The Gift of Death from Ancient Rome to the Aztec Empire

- 4 The European Way of War From Abattoir Christianity to Godforsaken Total War

- 5 Enlightened Killing From the Delicacy of the Wet Guillotine to the Damp Squib of Electrocution

- 6 The Animal Slaughter Industry Perfect Cities of Blood – Paris and Chicago

- 7 The Human Slaughter Industry War-machines, Speed-space, and Shell Shock

- 8 Weaponized Air From Forced Euthanasia to Military Ballooning

- 9 Atmospheric Terrorism Exterminatory Air Conditioning

- 10 Black Meteorology Experimental Airquakes and Lethal Landscapes

- 11 Firestorms and Corpse Mines The Optimism of Imprecision in Incinerated Cities

- 12 Capital Punishment A Race of Outcasts Reduced to the Status of Ordinary Men

- 13 The Business of Genocide Desk Murderers and Calculated Killers

- Still Dead Certain

- References

- Index