![]()

Part I

The Big Picture

![]()

Chapter 1

Adaptive Challenges for School Leadership

Marty Linsky and Jeffrey Lawrence

Abstract

The challenges facing education today must be seen in the broader context of the challenges facing society.

The singular reality is that none of us has been here before. Educational leadership will require different behaviours from those we have practised and perfected.

For example, we will spend more time running experiments than solving problems, more time adapting than executing, more time surfacing difficult values choices and orchestrating those conflicts than resolving them, and more time inventing next practices than searching for best practices.

Educational leadership will require becoming expert at working through competing commitments such as autonomy and standardisation or fairness, or accountability and fairness.

To take advantage of these opportunities will require learning new ways and the courage to step out and take responsibility for the future, whatever your place in the system.

Key words/phrases

Educational leadership; adaptive leadership; orchestrate conflict; competing commitments; experimentation; take care of yourself; hunker down; adaptive challenges versus technical problems.

The times we are in

The challenges facing school leadership in the early years of the second decade of the 21st century are intimately entangled with the broader, deeper challenges facing the global community, reaching far beyond the distinctive qualities of education.

We are in a period that feels unique, at least in your life experience, and in ours. The question is whether we are in the midst of a bump in the road or a sea change. Is this an emergency, or a crisis? An emergency is when your house is on fire; a crisis is when it has burned to the ground. An emergency is when you break your leg; a crisis is when you lose it.

Let’s look at the times we are in.

Foremost, of course, is the global economic turmoil. Ireland is painfully at the epicentre, still reeling from the bursting of the housing bubble and mourning the long-lost Celtic Tiger. But the world’s financial problems are only one element of the strange new world we find ourselves in.

Look at the data.

We are looking at extraordinary environmental and climate challenges. The glaciers are melting. Long-standing patterns of planting and harvesting are changing. There are places on the globe where the shortage of fresh water is an immediate concern. Technology is evolving rapidly. Amazon now reports that they are selling more books for Kindle, their electronic reader, than in hardcover. Five hundred million people are on Facebook.

A by-product of both the technology explosion and the implications of 9/11 is the reality of our interconnectedness. Everything is connected to everything else. Any intervention into the system is going to have consequences, intended or not, in lots of other places.

The Baby Boomer generation is ageing. While the economic problems have slowed retirements, there is a generation and talent gap as those folks born between 1946 and 1965 begin to retire and pass on in large numbers. While they are still around, the sheer number of Baby Boomers will give them a huge influence in society’s value choices, including, most pertinently to education, the allocation of public resources. The Millennials, the offspring of those Boomers, are emerging with a very different set of values around issues of privacy, loyalty, and whether work is the centre of life.

The global power structure is rebalancing. US and Western hegemony is giving way to the emergence of new potential super-powers such as China, India and Brazil. Wars are no longer between countries. The challenge to stability comes more and more from loosely or not so loosely connected groups who do not carry a national flag.

In short, we are indisputably in a period of rapid and constant change, greater uncertainty about the future than we have ever experienced, and inadequate information on which to make important choices. This is the context in which the challenges facing education in Ireland exist and in which this book is being written.

In education, as elsewhere, we are living at a time when, as Charles Dickens described a different world in a different era in his opening line of A Tale of Two Cities, ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times’. The central question is whether everyone concerned with the education of our children can seize this crisis as a time for innovation and change, or will continue to hunker down, preserve what they can, and hope that they survive more or less intact whenever things return to ‘normal’. The guess here, based on the data we just discussed, is that the new normal will not feel like normality at all, either in its content or its consistency.

So in one sense this is an extraordinary moment to be caring about education. The challenges have never been greater, the opportunities never more present, and the need for success never more critical. All the familiar norms are in play. The authority relationships among the government education agencies, the school administrators, the specialists, the teachers, the students, the parents, private education initiatives, the religious education establishment, and the broader community are all potentially in transition. The good news and the bad news is that there is a public sense of urgency about the global as well as local significance of how we educate our young people that is more palpable than at any time in our memories.

Assumptions about school leadership

If we are going to talk about school leadership in these extraordinary times, let’s begin with some assumptions about what we mean by leadership.

First, leadership is a complex but not a technical subject. There are no quick fixes, no easy answers, or, Stephen Covey notwithstanding, no seven quick behavioural changes which will enable you to exercise leadership more often or more effectively than you have in the past. We assume that everyone in the education sector is on the frontiers of leadership.

Second, leadership is an activity, not a person. Leadership is something some people do some of the time. It’s a verb, not a noun. No one exercises leadership 24/7. And our assumption is that if everyone reading these words exercised leadership more often than they do, including you, the world in general, and the world of education in particular, would be a better place.

Third, the opportunities to exercise leadership come to each of us, every day, at the family dinner table, in the workplace, in our community and civic lives. And the opportunities come independent of position. Leadership is not the exclusive prerogative of people in positions of authority. Quite to the contrary, some of the most extraordinary leadership has come from people with no formal authority at all (see Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, Jr) and people in positions of authority typically do not exercise leadership very much because doing so would put their authority and all the perquisites that go with it at risk. In the education sector, leadership can come from any of the interested factions: teachers, students, administrators, parents, government officials, businesspeople, or electeds.

Fourth, leadership can be learned. The only people we know who think that the capacity for leadership is inherited are those who think they have it. No, leadership is about courage and skill. And both the courage and the skills can be learned. As with young athletes, there may be some people who seem to start out with an advantage, based on how they look or the way they are wired emotionally. But the young athletic phenoms are often not the stars in later years because others have worked really hard to learn and perfect the skills which are necessary for athletic success. Similarly for leadership. Those God-given qualities may provide some people with a head start at developing leadership capacity, but others can easily surpass them by working hard to learn, practise and perfect their own leadership skill set.

What makes school leadership difficult?

We assume that everyone reading these words cares about quality education. And that you would not be reading this book unless there was a gap between your aspirations for education and the current reality. And we also assume that you are looking here for solutions that would be easy to apply or at least steps you could take that would likely make progress without, as the old proverb goes, breaking too many eggs. But leadership in education, as in any other sphere, is difficult work. That is one of the reasons why you – and we – do not exercise leadership more often.

In our view, too much time is spent on the inspirational aspects of leadership and too little time on the perspirational. Here’s what makes school leadership so difficult: the most common cause of failure in leadership comes from treating what we call adaptive challenges as if they were technical problems. What’s the difference?

While technical problems may be very complex and critically important (such as replacing a faulty heart valve during cardiac surgery), they have known solutions. They can be resolved through the application of authoritative expertise and through the organisation’s current values and ways of doing things.

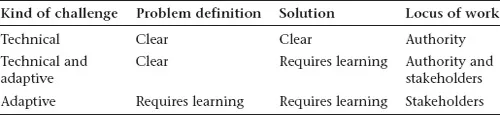

Adaptive challenges can only be addressed through changes in people’s values, beliefs, habits and loyalties. Making progress on them requires going far beyond any authoritative expertise and in particular dealing with the resistance that stems from unwillingness to face the losses that will be involved. This resistance makes adaptive leadership dangerous, and therefore rare. Table 1.1 below lays out some differences between technical problems and adaptive challenges.

As Table 1.1 implies, problems do not always come neatly packaged as either ‘Technical’ or ‘Adaptive’. When you take on a new challenge in your education work, whether in a classroom or as an administrator or policymaker, the challenge does not arrive with a big ‘T’ or ‘A’ stamped on it. Most problems come mixed, with the technical and adaptive elements intertwined.

Table 1.1 Distinguishing between technical problems and adaptive challenges

Here’s a homey example. At the time of writing, Marty’s mother, Ruth, is in good health at age 96. Not a grey hair on her head (although she has dyed a highlight in her hair so that people will know that the black is natural). She lives alone and still drives, even at night. When Marty goes from his home in New York City up to Cambridge, MA to do his teaching at the Kennedy School at Harvard, Ruth often drives from her apartment in a nearby suburb to have dinner with him.

Some time ago, Marty began noticing new scrapes on her car each time she arrived for their dinner date. Now, one way to look at the issue is that the car needs to be taken to a garage to be repaired. In that sense, this situation has a technical component: the scrapes can be solved by the application of the authoritative expertise found at the garage. But an adaptive challenge is also obviously lurking below the surface. Ruth is the only one of her contemporaries who still drives at all, never mind at night. Doing so is a source of enormous pride (and convenience) for her, as is living alone, not being in a retirement community, and still functioning more or less as an independent person. To stop driving, even just to stop driving at night, would require a huge adjustment from her, an adaptation. (She would have to rely on others, pay for cabs, ask friends to drive her places, use services for the elderly, and so forth.) It would also be a loss, a loss of an important part of the story she tells herself about who she is as a human being, namely, the only 96-year-old person she knows who still drives at night. It would rip out part of her heart, and take away a central element of her identity as an independent woman. Addressing the issue solely as a technical problem would fix the car (although only temporarily, since it is likely that the trips to the garage would come with increasing frequency), but it would not get at the underlying adaptive challenge.

In the corporate world, we have seen adaptive challenges with significant technical aspects arise when companies merge or make significant acquisitions. There are huge technical issues such as merging IT systems and offices. But it is the adaptive elements that threaten success. Each of the previously independent entities must give up some elements of their own cultural DNA, their dearly held habits and values, in order to create a single firm and enable the new arrangement to survive and thrive. We were once called in to help address that phenomenon in an international financial services firm where, several years after the merger, the remnants of each of the legacy companies are still doing business their own way, creating barriers to collaboration, global client servicing, and cost efficiencies. Whenever they get close to changing something important to reflect their one-firmness, the side that feels it is losing something precious in the bargain successfully resists. The implicit deal is pretty clear: you let us keep our entire DNA, and we will let you keep all of yours. They have been able to merge only some of the basic technology and communications systems, which made life easier for everyone without threatening any dearly held values or ways of doing business. In a similar client case, a large US engineering firm functions like a franchise operation. Each of their offices, most of which were acquired, not home grown, goes its own way, although the firm’s primary product line has become commoditised and the autonomy that has worked for these smaller offices in the past, and is very much at the heart of how they see themselves, will not enable them to compete on price for large contracts going forward.

We have seen the same commoditisation of previously highly profitable distinctive services also affecting segments of the professional services world such as law firms, where relationship-building has been a core strategy and value and where competing primarily on price is a gut-wrenching reworking of how they see themselves. Yet, as previously relationship-based professions are coping with the adaptive challenge of commoditisation of some of their work, the reverse process is simultaneously going on in many businesses that have been built on a product sales model and mentality.

In an increasingly flat, globalised 21st century world, where innovation occurs so quickly, just having the best product at any moment in time is not a sustainable plan. So, like one of our clients, a leading global technology products company, these companies are trying to adapt, struggling to move from a transaction-based environment, where products are sold, to a relationship-based environment where solutions are offered based o...