eBook - ePub

The SAGE Handbook of Transport Studies

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The SAGE Handbook of Transport Studies

About this book

The SAGE Handbook of Transport Studies is an authoritative survey of contemporary transportation systems examined in terms of economic, social, and technical issues, as well as environmental challenges. Incorporating an extensive range of approaches - from modes, terminals, planning and policy to more recent developments related to supply chain management, information systems and sustainability/ecology - the work provides a cohesive and extensive overview of transport studies.

Authored by international experts in their field, each individual chapter bridges a broad range of conceptual, theoretical and geographical perspectives, and the Handbook is divided into six sections:

• Transport in the Global World

• Transport in Regions and Localities

• Transport, Economy and Society

• Transport Policy

• Transport Networks and Models

• Transport and the Environment

This Handbook will be an indispensible resource for academics, planners, and policy-makers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The SAGE Handbook of Transport Studies by Jean-Paul Rodrigue, Theo Notteboom, Jon Shaw, Jean-Paul Rodrigue,Theo Notteboom,Jon Shaw,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Transportation Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

Transport in the Global World

2

Transport and Globalization

TRADE AND THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

The emergence of interdependencies

In a global economy, no nation is self-sufficient. Each is involved at different levels in trade to sell what it produces, to acquire what it lacks and also to produce more efficiently in some economic sectors than its trade partners. As supported by conventional economic theory, trade promotes economic efficiency by providing a wider variety of goods, often at lower costs, notably because of specialization, economies of scale and the related comparative advantages (Porter, 1990; Feenstra, 2004). The globalization of production is concomitant to the globalization of trade as one cannot function without the other. Even though international trade took place centuries before the modern era, as ancient trade routes such as the Silk Road can testify, trade has occurred at an ever-increasing scale over the last 600 years to play an even more active part in the economic life of nations and regions (Braudel, 1982; Bernstein, 2008; Bairoch and Kozul-Wright, 1996). This process has been facilitated by significant technical changes in the transport sector (Gilbert and Perl, 2008). The scale, volume and efficiency of international trade have all continued to increase since the 1970s. As such, space/time convergence was an ongoing process that implied a wider market coverage could be accessed with a lower amount of time. It has become increasingly possible to trade between parts of the world that previously had limited access to international transportation systems. Further, the division and the fragmentation of production that went along with these processes also expanded trade. Trade thus contributes to lower manufacturing costs.

Without international trade, few nations could maintain an adequate standard of living. With only domestic resources being available, each country could only produce a limited number of products and shortages would be prevalent. Global trade allows for an enormous variety of resources – from Persian Gulf oil, Brazilian coffee to Chinese labor – to be made more widely accessible. It also facilitates the distribution of many different manufactured goods that are produced in different parts of the world to what can be labeled as the global market. Wealth becomes increasingly derived through the regional specialization of economic activities. This way, production costs are lowered, productivity rises and surpluses are generated, which can be transferred or traded for commodities that would be too expensive to produce domestically or would simply not be available. As a result, international trade decreases the overall costs of production worldwide. Consumers can buy more goods from the wages they earn, and standards of living should, in theory, increase. International trade is also subject to much contention since it can at times be a disruptive economic and social force as it changes the conditions through which wealth is distributed within a national economy, particularly due to changes in prices and wages.

The flows of globalization

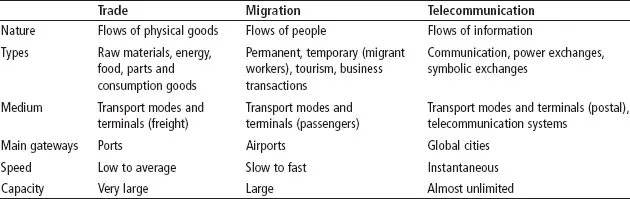

International trade consequently demonstrates the extent of globalization with increased spatial interdependencies between elements of the global economy and their level of integration. These interdependencies imply numerous relationships where flows of capital, goods, raw materials and services are established between regions of the world. There are three main types of flows in a global economy (Table 2.1):

- Freight (trade). Concerns flows taking place to satisfy material demands ranging from raw materials to finished goods. This is mainly assumed by maritime shipping, which is supported by port infrastructures acting as the main gateways of this flow system, but airports play an important role in the trade of high-value goods.

- Passengers (migration). The flows of people taking place for a variety of reasons, most of them related to tourism, with air transportation being the dominant mode supporting such flows. The global air transport system can handle about four million passengers per day.

- Information (telecommunications). The complex and extensive flows of information used for communication, power exchanges (e.g. an online order) and symbolic exchanges (e.g. education). Information flows can take both physical (e.g. parcels) and non-physical forms, which are dominantly articulated by a network of global cities.

Emergence of the global trade system

The emergence of the global trade system can mainly be articulated within three major phases. The first phase concerns a conventional perspective on international trade that prevailed until the 1970s where factors of production were much less mobile. Particularly, there was a limited level of mobility of raw materials, parts and finished products in a setting which was fairly regulated with impediments such as tariffs, quotas and limitations to foreign ownership (Bernstein, 2008). Trade mainly concerned a range of specific products, namely commodities (and very few services), that were not readily available in regional economies. Due to regulations, protectionism and fairly high transportation costs, trade remained limited and delayed by inefficient freight distribution. In this context, trade was more an exercise to cope with scarcity than to promote economic efficiency.

Table 2.1 The flows of globalization

From the 1980s, the mobility of factors of production, particularly capital, became possible, which permitted the setting of the second phase (Baldwin and Martin, 1999). The legal and physical environment in which international trade was taking place incited a better realization of the comparative advantages of specific locations (e.g. Daniels, Radebaugh and Sullivan, 2010). Concomitantly, regional trade agreements emerged and the global trade framework was strengthened from a legal and transactional standpoint (GATT/WTO). In addition, containerization provided the capabilities to support more complex and long-distance trade flows, as did the growing air traffic. Due to high production (legacy) costs in old industrial regions, activities that were labor intensive were gradually relocated to lower-cost locations. The process began as a national one, then went to nearby countries when possible and after-wards became a truly global phenomenon. Thus, foreign direct investments surged, particularly towards new manufacturing regions as multinational corporations became increasingly flexible in the global positioning of their assets.

The third phase marks the setting of global value chains with international trade now including a wide variety of services that were previously fixed to regional markets and a surge in the mobility of the factors of production. Since these trends are well established, the priority is now shifting to the geographical and functional integration of production, distribution and consumption with the emergence of global production networks (Dicken, 2007). Complex networks involving flows of information, commodities, parts and finished goods have been set, which in turn demands a high level of command of logistics and freight distribution. In such an environment, powerful actors have emerged that are not directly involved in the function of production and retailing, but mainly taking the responsibility of managing the web of flows.

The global economic system is thus characterized by a growing level of integrated services, finance, retail, manufacturing and nonetheless distribution, which in turn is mainly the outcome of improved transport and logistics, a more efficient exploitation of regional comparative advantages and a transactional environment supportive of the legal and financial complexities of global trade.

Trade surge

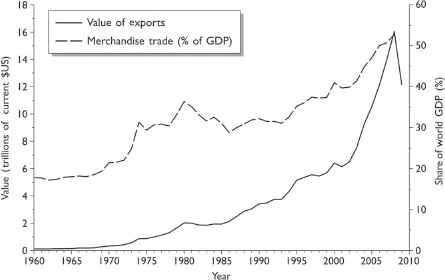

As of the beginning of the 21st century, the flows of globalization have been shaped by three salient trends. The first is an ongoing growth of international trade, both in absolute terms and in relation to global national income. Since the late 1970s the value of international trade has grown by a factor of 16 times if measured in current dollars (Figure 2.1). The second is a higher relative growth of trade in Pacific Asia as many economies developed an export-oriented development strategy that has been associated with imbalances in commercial relations. The third is the growing role of multinational corporations as vectors for international trade, particularly in terms of the share of international trade taking place within corporations.

Global trade has grown both in absolute and relative terms, especially after 1990 when global exports surged in the wake of rapid industrialization in developing countries, particularly China. The value of global exports first exceeded US$1 trillion in 1977, and by 2008 more than 16 trillion current US dollars of merchandises were exported. During the same time period, the share of the world GDP accounted by merchandise trade, imports and exports combined, surged from 18% to 52%. This trend is correlated with a growth in international transportation. Yet, this fast growth is skewed by the international division of production where parts can be traded several times before an assembled good is ready for final consumption.

Figure 2.1 World merchandise trade, 1960–2010

Source: WTO

The growth of exports is indicative of a diffusion cycle where globalization may have reached maturity, particularly in light of the acceleration phase that took place after 2001. This process cannot go on indefinitely as growth in trade was also accompanied by a surge in trade imbalances. The financial crisis of 2008–2009 was accompanied by a significant decline of global merchandise trade, close to 25% in just one year. The main factor behind this decline was a drop in the consumption of durable goods (e.g. furniture, appliances, cars) since consumers are able to postpone these type of purchases if they are uncertain about the future.

Trade imbalances

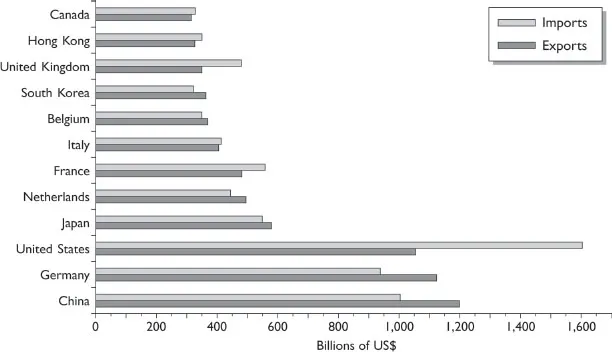

An overview of the world’s largest exporters and importers underlines that international trade reflects market size but is also characterized by acute imbalances (Figure 2.2). The United States, Germany, China and Japan are the world’s largest importers and consequently the world’s largest economies. In recent years Germany overtook the traditional position of the world’s largest exporter held by United States over the last 50 years. The integration of China within the global economy has been accompanied by a growing level of participation in trade both in absolute and relative terms, improving the rank of China from the seventh largest exporter in 2000, to the third largest in 2005 and finally to the largest in 2008, supplanting the United States and Germany.

With respect to trade imbalances, some countries, notably the United States and the United Kingdom, have significant trade deficits which are reflected in their balance of payments. This aspect is dominantly linked with service and technology-oriented economies that have experienced a relocation of laborintensive production activities to lower-cost locations. They are highly dependent on the efficient distribution of goods and commodities. Conversely, countries having a positive trade balance tend to be export-oriented with a level of dependency on international markets. Germany, Japan, South Korea and China are among the most notable examples. China has a positive trade balance, but most of this surplus concerns the United States. It maintains a negative trade balance with many of its partners, especially resources providers (e.g. Australia).

Acute trade imbalances cannot be maintained indefinitely without a readjustment. The surge in international trade, particularly after 2002, was linked with a phase of asset inflation (i.e. the real estate bubble), particularly in the United States and several European countries (e.g. United Kingdom, Spain) coupled with heavy borrowing using these assets as collateral. A share of this debt was used for the purpose of consumption of imported goods, which turned out to be unsustainable. Over the coming years, global trade will be significantly readjusted to better reflect production and consumption capabilities.

Figure 2.2 The world’s 12 largest exporters and importers, 2009

Source: WTO

TRADE FACILITATION

Trade costs

The volume of exchanged goods and services between nations is taking a growing share of the generation of wealth, mainly by offering economic growth opportunities in new regions and by reducing the costs of a wide array of manufacturing goods. By 2007, international trade surpassed 50% of global GDP for the first time, a twofold increase in its share since 1950 (see Figure 2.1). The facilitation of trade involves seeing how the procedures regulating the international movements of goods can be improved. It depends on the reduction of the general costs of trade, which considers transaction, tariff, transport and time costs, often labeled as the “Four Ts” of international trade:

- Transaction costs. The costs related to the economic exchange behind trade. It can include the gathering of information, negotiating, and enforcing contracts, letters of credit and transactions, including monetary exchange if a transaction takes place in another currency. Transactions taking place within a corporation are commonly lower than for transactions taking place between corporations. Still, with e-commerce they have declined substantially.

- Tariff and non-tariff costs. Levies imposed by governments on a realized trade flow. They can involve a direct monetary cost according to the product being traded (e.g. agricultural goods, finished goods, petroleum, etc.) or standards to be abided by for a product to be allowed entry into a foreign market. A variety of multilateral and bilateral arrangements have reduced tariffs and internationally recognized standards (e.g. ISO) have marginalized non-tariff barriers.

- Transport costs. The full costs of shipping goods from the point of production to the point of consumption. Containerization, intermodal transportation and economies of scale have reduced transport costs significantly.

- Time costs....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION 1: TRANSPORT IN THE GLOBAL WORLD

- SECTION 2: TRANSPORT IN REGIONS AND LOCALITIES

- SECTION 3: TRANSPORT, ECONOMY AND SOCIETY

- SECTION 4: TRANSPORT POLICY

- SECTION 5: TRANSPORT NETWORKS AND MODELS

- SECTION 6: TRANSPORT AND THE ENVIRONMENT

- Index