- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Coaching Relationship in Practice

About this book

This book explores that which is at the very heart of coaching: the coach-coachee relationship. Considering the relationship at each stage of the coaching process, it will equip your trainees with the necessary skills and knowledge for building and maintaining successful coaching relationships every step of the way.

In clear and friendly terms the book simplifies complex issues including the practicalities of getting started, the intricacies of coaching across cultures and of coaching from within an organisation, and how to make the most of supervision. A crucial chapter on evidence-based practice considers the importance of research in the area and how to use the evidence-base to support professional coaching practice. Reflective questions, examples, implications for practice and recommended reading are included in every chapter, encouraging your trainees to consider how they might bring themselves to the coaching relationship.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Getting Ready: Gathering the Resources to Begin Coaching

I like the metaphor of a journey for describing the kind of experience you are likely to have as you get ready for coaching, because there is no doubt that you’ll have a sense of having travelled some distance by the time you complete your programme and feel ready to say ‘I am a coach’.

In fact the metaphor touches something very real, as delegates regularly say they are on a journey, and knowing them and the changes they have been through I can only agree, often in a very moving and heartfelt way. It is a journey of personal and professional development, and it is very likely that on your own journey you too will make some important decisions about your life and its future direction. Coaching has that effect.

So what resources do you need to get ready to meet your first coachee? Let’s look at four, and consider the relational implications of each:

- Clarity about what we mean by coaching.

- A theoretical framework for practice.

- The skills to implement an awareness-raising coaching approach.

- A way of structuring the session.

1. Clarity about what we mean by coaching

As we shall see, there are many definitions and descriptions of coaching, but it’s important that you ask yourself this question first because it’s likely you’ll already have much of the answer. Coaching is a familiar word, used in a variety of contexts, and it’s possible that you, or people you know, have already had some involvement with it.

Here are some definitions – see how they line up with your understanding:

- Coaching is the facilitation of learning and development with the purpose of improving performance and enhancing effective action, goal achievement, personal satisfaction and fulfilment of potential. It invariably involves growth and change, whether that be in perspective, attitude or behaviour. (Bluckert 2006)

- Coaching is about change and transformation – about the human ability to grow, to alter maladaptive behaviours and to generate new, adaptive and successful actions. (Skiffington and Zeus 2000)

- Coaching is a process that enables learning and development to occur and thus performance to improve. (Parsloe 1999)

- Coaching is unlocking a person’s potential to maximise their performance. (Whitmore 2009)

My view, which is rooted in the existential approach mentioned in the Introduction, draws on the metaphor of journey. It is about assisting someone to gain a sense of direction and purpose, which is often lost in the absorption with everyday life, and then set out on their self-chosen path. Coaching is about enabling someone to find their own next step, and to take this step in a skilful and effective way.

How do these definitions and my view line up with, differ from or shift your view of coaching?

However you position yourself amongst the overlapping definitions, the most fundamental principle of coaching is that people have the capability to take responsibility for, and make decisions about, their own lives, rather than someone else doing this for them. This statement is highlighted as it is the bedrock for all that follows.

Like any manifesto, such a statement is easy to sign up to, and in my experience it strikes a deep chord in people. Yet it can be an extraordinarily hard creed to live up to because we live in a culture where people are told what to do, through advice, suggestions, direction and instruction. Telling is a deep-rooted habit. Parents, friends, teachers, doctors, you and I: most of us do it and do it most of the time. If you want the evidence for this just listen to others and to yourself. You’ll hear variations on: ‘What about...’; ‘I think it would be a good idea to...’; ‘Have you tried...’

There are profound personal and professional issues in play here, as the tell approach is based upon what might be termed a ‘deficit model’ of relating, i.e. the person I am talking to lacks something which I will provide. Culturally this attitude is rooted in familiar background practices that are so taken for granted that we hardly notice them, and which create expectations on both sides: for example, going to the doctor for advice about what is wrong and what to do. At a more personal level, for most of us, for much of the time, there is a pervasive background belief that the other person lacks something or cannot manage, and therefore we have to step in and provide what is needed. This tendency is likely to be reinforced by a sense that my self-worth is at stake: to be of any value, of any use, I must be able to offer something to help, and this ‘something’ takes the form of telling. Telling is often driven by the anxiety of not knowing what else to do and the fear of being useless.

What about from the other side of the coin? What is your experience of being told? Do you want advice and guidance? Do you invite it? How do you react? I know for me there are times when I do want to be told, for example when I go to the doctor. I also know that at times I have a visceral reaction against being told, and can get quite angry. It may be, for example, that I am about to go into an important meeting and someone starts to give me advice about how I should handle it; or I set off in the car and the person next to me tells me the route I should take.

If this sounds familiar, then the fundamental personal and professional challenge is developing the belief that people have the capability to make decisions about their own lives; they don’t need me to do it for them. The expression from transactional analysis ‘I’m OK – you’re OK’ (Harris 2012) catches the basic stance of coaching. It means that, in essence, we are both capable of taking responsibility for our lives. It alerts me to the possibility of two familiar shifts in the relationship: ‘I’m OK – you’re not OK’, and ‘I’m not OK – you’re OK’. In the first situation (which leads to ‘tell’) I think I am more capable than you and that you need something from me. In the second situation I think you are more capable than me, and I want you to tell me what to do. The expression is a sensitive measure of whether or not I am in the right kind of relationship with you. I recommend you try it out for yourself.

What is involved in implementing the belief that other people have the capability to find their own way forward? We shall see below that there are a range of skills that you can learn that are fundamental to coaching, and are good to have in place when you meet your first coachee. But before we get into the details of those skills, let’s consider more broadly what is involved in helping someone find their own way.

You’ll recall from the Introduction that from a relational point of view the coaching relationship is co-created. Put simply, you as the coach will inevitably influence the coachee. How can this be compatible with the coachee’s autonomy and responsibility? This is a hard question, and one to which we shall return repeatedly throughout the book as we explore more deeply the issues involved. Nevertheless, some initial thinking is important, if for no other reason than to avoid falling into the position of believing that coaching is mostly about models, techniques and skills, which if properly applied will be all that is required – a position that tends to treat people as objects, as passive ‘things’ to be changed (‘If I do this – use this model or skill – then that will happen’).

One way into this is to think about how you are in other relationships when you want to be of assistance, whether as a parent, a friend or a colleague. What is involved? Where is the line between enabling and taking over? The basic question remains the same: do you believe that the other person has the capability to take responsibility and make their own decision? If you don’t believe in their capability then you’re likely to tell. I know I am most prone to tell when anxious, so have to watch out when I notice anxiety stirring in me. A more useful response is to ask myself, and maybe the other person, what is needed and how can I meet that need in a way that respects their autonomy? For example, you might say something like ‘Tell me a bit more about that’ or ‘What are your thoughts about it?’ The notion of ‘resourcing’ can be useful here: how can you help resource the person, both internally and externally, to enable them to address what matters? And when is something other than asking appropriate – when perhaps they are so overwhelmed by a situation that something more is needed from you? These reflections are flagging up that whatever we choose to do will influence the relationship, and the choices made as to the best course of action are a matter of personal and professional judgement. In coaching, the same sort of judgements have to be made, and at times it is hard to know what is best to do.

There is real value in addressing these issues during coach education and training. There is a great opportunity to examine, in practice, your usual taken-for-granted habits of intervening, and get an understanding of the triggers that invite you to act in certain ways. In the initial stages you’ll probably feel the strain of holding back from what you normally do, as you develop a mindset and the skills that offer you the choice of doing something different. It is likely you’ll initially feel deskilled as you restrain from familiar behaviours and learn new ones. These skills will open up new possibilities in your relations with others, and widen the range of responding. They won’t take away some of the dilemmas you’ll encounter, but they will offer greater awareness and additional ways of resourcing others.

Before reading on, jot down your understanding of coaching:

- What is it?

- What is it for?

- What are its core principles?

In doing this you will begin to establish your own viewpoint which will no doubt shift and change, but you will have begun to articulate your own position from which to evaluate what I and others are saying.

I’d like you to take some time to think about what I’ve said here and consider whether it tallies with your own experience.

- What part does ‘tell’ play for you as a parent, as a friend, or in your professional life?

- What is your first move when someone is in difficulty?

2. A theoretical framework for practice

If we are to change our usual habitual ways of working it’s important to have a framework that makes sense of, and provides guidelines for, this different approach. All that follows in this book is founded on the notion that ‘meaning making’ is fundamental to being human. We are always seeking and attributing meaning to events, from the smallest act of perception (e.g. that moment of confusion when a ‘fly’ nearby is suddenly a ‘plane’ a long way away) to the broadest social, political and philosophical systems. The ‘facts’ never ‘speak for themselves’, they only do so from within a pre-existing set of beliefs. This becomes obvious when, for instance, we hear politicians from different parties argue about the same issue, but differ completely and systematically about the nature and meaning of what is going on. In a sense they live in ‘different worlds’. No doubt you’ve regularly experienced the same sort of thing when you’ve had disagreements with family, friends and colleagues at work – people see things very differently; the facts differ depending upon the viewpoint.

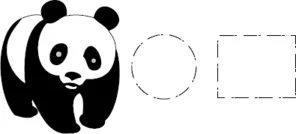

The gestalt school of psychology explored this meaning making in perception in the early decades of the twentieth century, and their analysis is important for us here. Gestalt is a difficult word to translate, but it basically means that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, and that, crucially, when we perceive something we do so immediately as a meaningful whole. For example, I hear a car door slam, or footsteps along the path, rather than a collection of different sounds which I then add together to infer what I’ve heard. The gestalt psychologists gave many examples of how we immediately ascribe meaning, ‘completing’ patterns that go beyond what is given to perception (see Figure 1.1).

I would anticipate that you will find it hard, if not impossible, not to see a panda, a circle and a rectangle in Figure 1.1, yet in fact each figure is incomplete. The ‘panda’ is an arrangement of black marks on a white background; the ‘circle’ and ‘rectangle’ are just some broken lines.

Figure 1.1 Completing incomplete patterns

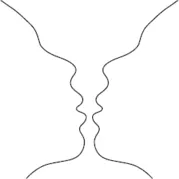

The gestalt psychologists demonstrated that in an ambiguous situation there is the possibility of seeing more than one meaningful pattern, using what are now very familiar images (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

You can probably easily see the vase/faces and, perhaps less easily, faces of a young/older woman in Figures 1.2 and 1.3. Notice again that you’ll be seeing each as a meaningful whole – for example, either as a black vase or white faces (rather than black marks on white backgrounds).

Notice in addition that you’ll not be able to see both images at the same time, e.g. you’ll not be able to see both young and older women’s faces in the same moment (though you may switch perception from one to the other very quickly). This is because perception is organised around meaningful wholes, which the gestalt psychologists analysed in terms of ‘figure’ and ‘ground’, concepts that will be important throughout this book. The ‘figure’ is the something we ‘see’, the meaning we attribute to what we perceive: so the figure may be the black vase or the white faces, or the young or older woman’s face. Each figure takes on meaning through a particular way of organising the ‘ground’ (short for ‘background’) – the ‘source material’ for the figure. For example, the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Getting Ready: Gathering the Resources to Begin Coaching

- 2 Getting Started: The First Session

- 3 Self-Management

- 4 Relationship Management

- 5 Widening the Field

- 6 Culture, Difference and Diversity

- 7 Coaching in Organisations: Managing Complex Relationships

- 8 Supervision and Personal Development

- 9 Coaching Relationship in Practice: The Evidence Base

- Conclusion: Putting Your Signature on It

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Coaching Relationship in Practice by Geoff Pelham,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.