![]()

PART I

Principles

![]()

1 | Developing People and Competencies |

| | Robert B. Mellor |

Introduction

In this chapter the need for an entrepreneurial team is put forward, as is the need for a concrete strategy (normally documented in the form of the business plan) and a network. The latter part of the chapter introduces how these and related topics are further developed in this book.

Capitalizing on a bright idea

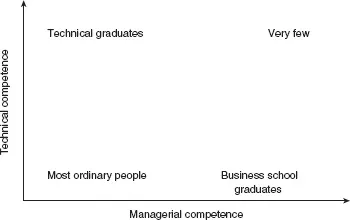

The concept of ‘the entrepreneurial inventor’ does not hold much water and indeed only a few of the classical ‘engineer entrepreneurs’ like Robert Stephenson, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Alexander Graham Bell have received both honours and economic reward for their efforts. But the majority of the great scientific inventive minds have not managed to make a lasting financial profit (e.g. Curie, Einstein, Marconi, Pasteur and Whittle) and today a pop star probably makes more money than 50 Nobel Prize laureates (see Chapter 15). Even Thomas Edison, founder of the Edison Electric Light Company (later to merge with the Thomson-Houston Company and be called General Electric), like many scientists and engineers, was not a good financial manager and despite all his incredible energy he managed to bankrupt several – if not most – of his ventures despite the fact that he held 1,093 US patents and 1,239 foreign patents, including those on the phonograph, motion pictures, the alkaline storage battery and synthetic rubber, as well as the first practical incandescent light bulb (note that the ‘incandescent filament lamp’ was invented by Joseph Swan, Edison bought the rights and made the process practical). Technical competence – the ability to make new things – can be plotted against managerial competence – the ability to get things done and products sold (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Plot of technical versus managerial competence. Very few inhabit the top right quadrant, although the multi-skilled (e.g. an engineer with an MBA) will tend away from the axes towards the middle and thus may be more innovative (see Chapter 2)

In contrast to inventors, the entrepreneurs often mentioned in connection with entrepreneurship, e.g. the late Anita Roddick (the Body Shop), Marks & Spencer, Tesco and Richard Branson (Virgin), achieved fame and fortune not by applying new technological inventions at all, but by using creative business models.

So having a bright technology-based idea is only the first of several factors needed to form a successful enterprise. The second factor is the other people involved in the business aspects of a technical idea and who can bring it forward, while the third factor is most often called ‘the network’. The combination of the second and third factors, judiciously applied, can go a long way to solving the budding entrepreneurs’ major problem, namely finding finance.

The entrepreneurial inventor

The career of Elmer Sperry offers an excellent example of the entrepreneurial inventor. Sperry was born into a New York family of modest means and after attending public schools, decided that he wanted to be an inventor. He tried to learn as much about electricity as possible from the library and courses, including attending lectures at nearby Cornell University. Acting on the suggestion of one of the professors there, he designed an automatically regulated generator capable of supplying a constant current when the load on its circuits varied and then immediately started to search for a financial backer. In 1880, he was taken in by the Cortland Wagon Company, whose executives included both inventors and investors and which provided him with the services of a patent lawyer, as well as money to live on and a workshop. In this ‘incubator’ Sperry not only perfected his dynamo, but over the next two years developed a complete system of arc lighting to go with it. Thus the Sperry Electric Light, Motor, and Car Brake Company was formed in 1883, with Sperry (who owned a large part of the company’s stock) serving as ‘electrician, inventor, and superintendent of the mechanical department’. Although the company was not a financial success, it launched Sperry’s career. He would go on to write more than 350 patents and found nearly a dozen companies including – with the help of a wide assortment of financial backers – the Sperry Electric Mining Machine Company, the Sperry Streetcar Electric Railway Company, and the Sperry Gyroscope Company. Although Sperry often played an active role in these companies in their early stages, he typically downgraded his role to the position of technical consultant and went on to a new project, once they were reasonably well established.

Sperry focused on ensuring that his inventions were commercially exploited as best possible and consequently sold many of his inventions to companies better placed to put them to productive use. Indeed, one of his firms was the Elmer A. Sperry Company of Chicago, formed in 1888 as a vehicle for his research and development activities and whose output was patented technology. Interestingly, this firm also advertised its business as helping inventors ‘develop, patent and render commercially valuable their inventions’.

(Source: Further researched from Hughes (1971))

How, then, can you combine excellence in technical subjects, with excellence in business? Clearly it is advantageous if you have a large family consisting of marketing people, lawyers, accountants, etc. and in the early 1990s it was rumoured that the single largest success factor for new start-ups was a high-earning spouse! Most individuals wishing to start up, however, are not in the privileged position of being able to surround themselves with the necessary expertise from their immediate family. As a consequence of this – and as illustrated in Chapter 6 – investors strive to surround the inventor with bought-in professionals possessing these skills.

Covering the business side

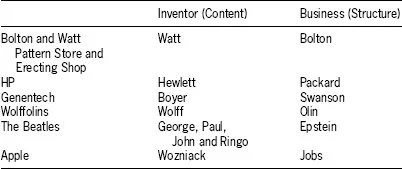

Another method is to team up with people possessing complementary skills from the start. This involves teaming up ‘content people’, often real experts in their field, with ‘structure people’, who can sell – no matter what it is. The right person may not necessarily be someone already known, or even liked (indeed taking best friends or family on board can lead to excruciating conflicts). It must, however, be someone that the inventor can trust to make good business decisions, to be highly motivated and someone who can work towards a common goal. This mixing factor has been a feature of leading undergraduate courses for some years (e.g. at the University of Nevada, Reno – see Wang and Kleppe, 2001; and at the IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark – see Mellor, 2003, 2005). The very positive effect of these synergies is often called the ‘Hewlett-Packard’ effect after the huge success of the Hewlett-Packard Company, which combined the technical brilliance of Hewlett with the business brains of Packard (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Illustrating the ‘Hewlett-Packard’ effect; ‘content’ people team up with ‘structure’ people to form a winning team

Entrepreneurship is often wrongly perceived as a solitary activity – this misconception is actually reinforced by terms such as ‘sole trader’. However, not only the high-profile examples cited in Table 1.1 but also the results of recent surveys e.g. Entrepreneurship and Local Economic Development, by the OECD (OECD, 2003) indicate that team-based business start-ups fare much better than individual start-ups. Specifically:

- In micro enterprises, partnerships exhibit higher rates of survival than individual firms.

- Investors are more likely to approve financing to team-led start-ups in early-stage venture capital assessments.

- The success of the firm and client satisfaction correlate well with the degree of social interaction in entrepreneurial teams.

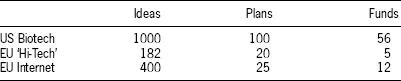

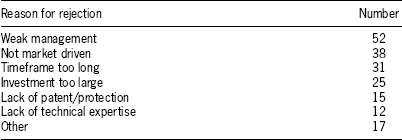

And, indeed, many of today’s leading corporations, like General Motors, DuPont, Coca-Cola and McDonald’s, were all set up by teams and not by individuals acting alone. Although not all business ideas will result in a new Hewlett-Packard or Apple, a strong sales team can sell most things, so investors can expect some Return on Investment (RoI). Unfortunately most new businesses are weak on the business side; whereas 91 per cent of high-tech start-ups are confident in their technical ability, only 27 per cent of high-tech start-ups are confident that they can get their product to the market on time (Mellor, 2003). This lack of proper management is seen as a major drawback by investors – who invariably know their business very well. It cannot be stressed enough that the business objectives are of paramount importance in setting up a business. One major indicator of the quality of the business acumen is the business plan. Table 1.2 illustrates that typically only few business plans receive funding and Table 1.3 illustrates that the reason for rejection is most often a poor management team.

Table 1.2 Number of business plans receiving funding in some common venture capital areas

Source: Modified from Mellor (2003).

Table 1.3 Commonly cited reasons for rejecting business plans

Source: Modified from Mellor (2003).

Since usually 100 ideas are needed to generate one business plan, the business plan needs not only to be excellent but must also address both technical and managerial issues.

The essential social and business network

The third ingredient for success is having a network. Networks are also useful in starting new companies as they provide a knowledge background. Since growing a company is full of uncertainties, it is not possible in advance to know which expert tips are going to be needed (i.e. heterogeneous knowledge is needed). Those entrepreneurs with an extensive network are therefore in a much stronger position to reply to external threats, changes in the market and similar challenges. They will be in a stronger position to innovate and overcome obstacles. This is the social capital that adds value to the company. Such social capital can be accessed formally or informally, e.g. on the web there exist many networks (communities) specifically to create this type of social capital, and where membership gives one the ‘right’ to approach others.

Network, finance and technical ability: the case of Silicon Valley

The importance of networking is perhaps best illustrated by the example of Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley is contained by the San Francisco Bay on the east, Santa Cruz Mountains on the west and the Coast Range to the southeast. Once – when fruit orchards predominated - it was called the ‘Valley of Heart’s Delight’. The San Francisco Bay Area has traditionally been a major site of US Navy work, as well as the site of the Navy’s large research airfield – including anti-submarin...