![]()

Part I

Identification and Provision

![]()

Chapter 1

Defining Giftedness

This chapter looks at:

- Definitions of giftedness

- Françoys Gagné’s differentiated model of giftedness and talent

- The role of the teacher

- A school-based definition

The term ‘gifted’ is frequently used to describe abilities demonstrated in sport or in the creative arts – ‘a gifted athlete’, ‘a gifted actor’ and so on. These references often apply to a specific ability, and may imply that this ability has appeared without systematic learning or teaching, and that those possessing such ‘gifts’ have somehow been endowed with their particular ability in a way that is beyond the control or scope of education, despite clear indications that the ‘gifted’ individuals have usually spent years honing their skills.

A number of terms are commonly used by teachers to describe ‘gifted’ pupils: bright, talented, high flier, exceptionally able, brilliant (George, 1995, 1997; Wallace, 2000). Teachers use these terms interchangeably to refer to pupils who have demonstrated particular abilities and for whom different educational provision is needed.

One definition is that gifted pupils have the potential to demonstrate superior performance in a number of areas, and talented refers to those who do this in a single area (George, 2000). Eyre’s (1997) multi-dimensional view of giftedness is a more complex one and she considers that ‘gifted and talented’ describes not only those with high academic abilities, but should also include those with musical, sporting or artistic ability.

Most definitions of giftedness in secondary school pupils refer to their abilities and achievements in particular areas, fitting the popular theory of multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1993) indicating different kinds of ‘giftedness’.

The English definition of ‘gifted’ learners as those who have abilities in one or more academic subjects and ‘talented’ learners as those displaying abilities in sport, music, design or creative arts is not universally accepted by researchers and educators, even across the United Kingdom. In Scotland, teachers often use ‘more able’ when referring to their highest achieving pupils (McMichael, 1998), while the Welsh Assembly used ‘more able and talented’ in their 2003 Guidance for Local Education Authorities.

In New Zealand giftedness is defined in terms of learning characteristics indicating the possession of special abilities that give pupils the potential to achieve outstanding performance (Riley et al., 2004). No specific definition of giftedness is given, but, as in many other ‘national’ guidance publications, schools are expected to develop their own definitions based on the published principles.

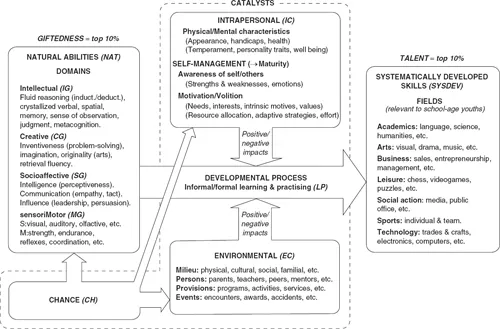

Most teachers would agree that gifted pupils are those who require greater breadth and depth of learning activities and extended opportunities across the curriculum in order to develop their abilities. The learning needs required by some pupils to develop their abilities is fully illustrated by Gagné’s (1985, 2003a) differentiated model of giftedness and talent (DMGT) (see Figure 1.1). In this, Gagné proposes that giftedness is the potential or aptitude within an individual, and that this can be developed into talent (developed abilities or high performance) by environmental and other factors.

This model explores what an individual needs to do in order to transform an aptitude into a developed skill. Gagné clearly defines giftedness as ‘natural’ abilities that may be made apparent through the ease and rate at which individuals acquire new skills – learning appears to be easier and faster in individuals whose natural abilities are high, but these aptitudes must pass through a developmental process before they can be demonstrated as ‘talents’ (systematically developed skills). Talent development requires systematic learning and practising, and the more intensive these activities are, the greater the demonstrated skills will be. In the DMGT, while one cannot be talented without first being gifted, it is possible for natural abilities not to be translated into talents, so that academic underachievement of some intellectually gifted pupils may be linked to a failure to engage fully in the developmental process.

ROLE OF THE TEACHER

What makes Gagné’s model particularly meaningful to teachers is the place given to the developmental process of learning, training and practice combined with environmental and intrapersonal catalysts which transform natural aptitudes into skills that can be publicly demonstrated. In sport, for example, coaches assess those athletes most likely to attain high levels of performance using not only natural abilities but also catalysts like intrinsic motivation, competitiveness, persistence and personality, while sports organisations provide the best environmental conditions to foster athletes’ development. Even chance plays a role! No matter how much natural ability a young athlete may have, and no matter how well trained and motivated (even with the very best of coaching and equipment), if the international selector does not see him perform, he may never attain at the highest levels. However, the teacher/trainer/coach will always try to ensure that protégées are given every opportunity to shine – and most of them will go to great lengths to eliminate chance as a factor that might prevent this.

In the DMGT, teachers are able to see a clear role for themselves in the transformation of natural aptitudes into developed skills. Learning implies a role for the teacher in devising programmes for pupils to follow in order to develop and improve their skills, while practice is undertaken by pupils themselves and linked to motivation and environmental circumstances, though supported by teachers through the provision of resources. Teachers can provide a motivating classroom environment by creating conditions that sustain, guide and enhance a pupil’s inherent motivation to learn; they can stimulate pupils’ interests and create a climate that promotes achievement by helping pupils accept and value their gifts; and they can provide resources that do not place limits on individual pupils’ attainments.

Figure 1.1 Gagne’s Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent (DGMT, US, 2003)

SCHOOL-BASED DEFINITION

Gifted educational provision in school may be a systematic form of intervention designed to foster the process of talent development in pupils. Such intervention does not depend on teachers’ adherence to any particular definition of giftedness, but is built on the awareness that some pupils are gifted and that the teacher’s role is to support their development.

Schools need to develop a definition of giftedness that:

- allows the recognition of both performance and potential;

- recognises that pupils may be gifted in one or more areas;

- reflects a ‘multiple intelligences’ approach that includes a range of special abilities;

- acknowledges that gifted and talented pupils demonstrate exceptionality in relation to their age-peers of similar backgrounds;

- provides for differentiated educational opportunities for gifted and talented pupils, including social and emotional support.

No matter what definition of ‘gifted’ is accepted, teachers need to see their own role in working with gifted pupils, and this may sometimes be obscured by the multiplicity of definitions.

The search for an absolute definition of giftedness to apply to pupils in the secondary school may be rooted in the fact that many gifted pupils have abilities that are not evident within the context of the school curriculum, so teachers are not in a position to create opportunities and offer experiences that promote a developmental process to enable these pupils to develop their skills. Some pupils allow the teacher only glimpses of their potential or ability, suggesting that appropriate educational provision for all in an inclusive setting might be necessary to encourage the most able to reveal themselves (Wallace, 2000).

FURTHER READING

Colangelo, N. and Davis, G.A. (eds) (2003), Handbook of Gifted Education, 3rd edn. Boston, MD: Allyn and Bacon

Gross, M.U.M., MacLeod, B. and Pretorius, M. (2001) Gifted Students in Secondary Schools Differentiating the Curriculum, 2nd edn. Sydney, Australia: Gerric

Renzulli, J.S. (1999) What is this thing called giftedness, and how do we develop it? A twenty-five year perspective’, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 23 (1): 3–54

Sternberg, R.J. and Davidson, J. (eds) (1986) Conceptions of Giftedness. New York: Cambridge University Press

![]()

Chapter 2

Identification of Giftedness

This chapter looks at:

- Identification procedures

- through provision

- teacher nomination

- profiling

- standardised tests

- checklists

- rating scales

- References for checklists and standardised tests

- Sources of identification checklists

- Example of a checklist

Some people consider that identification of individual children as gifted is elitist, yet these children are elite in the same way as anyone who becomes an Olympic medallist, a solo performer or a leader.

Generally, gifted pupils are thought to share common elements (Gross et al., 2001) such as the potential for unusually high performance and a capacity to think clearly, analytically and evaluatively. Identification of giftedness should be a flexible, continuous process that combines the assessment of ‘precocious achievement or behaviour’ with the creation of conditions that will ‘allow giftedness to develop and reveal itself’ (Eyre 2002a). In order to ensure that gifted pupils are given every opportunity for this to happen, and to prevent disadvantage on the basis of cultural, socio-economic background or disability, identification processes should be able to be carried out within an inclusive educational setting.

The responsibility for identifying gifted pupils lies with the school, specifically with individual teachers. Many teachers are fully aware that actual performance is not always an indicator of giftedness, so schools should establish a range of procedures for identifying gifted pupils that include methods designed to discover potential or ability not revealed by current performance. A range of approaches should be used to assess the ability or potential of pupils at the secondary school. Eyre (1997) lists information from the primary schools, tests and classroom observation; Freeman (1998) highlights teacher nomination, parent and peer recommendation and intelligence; while George (2000) includes tests of achievement and creativity along with checklists and rating scales.

IDENTIFICATION THROUGH PROVISION

Schools should have procedures in place for revealing pupil ability (Eyre, 2002a) and foster the emergence of individual pupils’ gifts and talents, including classroom environments that encourage creative, divergent and higher-level thinking with an open-ended approach to learning (Renzulli, 1999).

There may be difficulty in identifying gifted pupils with hidden potential; Freeman (2000) discusses a ‘sports approach’ that allows pupils to excel within the context of what is available to them – they could choose for themselves whether to participate and at what level. The benefits of using this approach to identify pupils’ abilities are:

- it is process-based and continuous;

- it uses multiple criteria;

- it could be validated for every course of action and provision;

- pupils’ abilities could be presented as a profile with the next learning stage...