- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Television Journalism

About this book

"Amidst the glut of studies on new media and the news, the enduring medium of television finally gets the attention it deserves. Cushion brings television news back into perfect focus in a book that offers historical depth, geographical breadth, empirical analysis and above all, political significance. Through an interrogation of the dynamics of and relations between regulation, ownership, the working practices of journalism and the news audience, Cushion makes a clear case for why and how television news should be firmly positioned in the public interest. It should be required reading for anyone concerned with news and journalism."

- Natalie Fenton, Goldsmiths, University of London

"An admirably ambitious synthesis of journalism scholarship and journalism practice, providing a comprehensive resource of historical analysis, contemporary trends and key data."

- Stewart Purvis, City University and former CEO of ITN

Despite the democratic promise of new media, television journalism remains the most viewed, valued and trusted source of information in many countries around the world.

Comparing patterns of ownership, policy and regulation, this book explores how different environments have historically shaped contemporary trends in television journalism internationally. Informed by original research, Television Journalism lays bare the implications of market forces, public service interventions and regulatory shifts in television journalism?s changing production practices, news values and audience expectations.

Accessibly written and packed with topical references, this authoritative account offers fresh insights into the past, present and future of journalism, making it a necessary point of reference for upper-level undergraduates, researchers and academics in broadcasting, journalism, mass communication and media studies.

- Natalie Fenton, Goldsmiths, University of London

"An admirably ambitious synthesis of journalism scholarship and journalism practice, providing a comprehensive resource of historical analysis, contemporary trends and key data."

- Stewart Purvis, City University and former CEO of ITN

Despite the democratic promise of new media, television journalism remains the most viewed, valued and trusted source of information in many countries around the world.

Comparing patterns of ownership, policy and regulation, this book explores how different environments have historically shaped contemporary trends in television journalism internationally. Informed by original research, Television Journalism lays bare the implications of market forces, public service interventions and regulatory shifts in television journalism?s changing production practices, news values and audience expectations.

Accessibly written and packed with topical references, this authoritative account offers fresh insights into the past, present and future of journalism, making it a necessary point of reference for upper-level undergraduates, researchers and academics in broadcasting, journalism, mass communication and media studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE ROLE OF NEWS IN TELEVISION CULTURE: CURRENT DEBATES AND PRACTICES IN CONTEMPORARY JOURNALISM

Television and the public sphere: journalism in a multi-channel environment

In making sense of television journalism, it is important to look beyond a particular headline or breaking news story in order to situate whatever purpose it serves more generally in society. Since television is where most people turn to understand what is happening in the world, what news is – and what is not – routinely included in an increasingly crowded and multichannel environment matters. It constitutes, like other media, a space that is commonly identified as the public sphere, a normative theory used widely in journalism studies to understand the role the media could (or should) play in society.

This theory was developed by a German scholar, Jürgen Harbermas, in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, which was originally published in 1962 and translated into English in 1989. It has, over the years, received comprehensive treatment (Calhoun 1992; Dahlgren 1995) and been related to far grander political, economic and philosophical arguments than the scope of this book can include. This is not the place to rehash or flesh out those debates. The public sphere is briefly summarised here as a means of characterising what television journalism can democratically make possible rather than something it can tangibly achieve. What the public sphere represents, in other words, is a normative rather than an empirical aspiration.

Put simply, Habermas (1989) charted an historical journey of how citizens, in post-feudal times between the seventeenth and mid-twentieth century, reached an understanding of the world that was independent of state forces. At the beginning of this period, when the early symbols of democracy (parliaments, newspapers) began to take shape, citizens met and exchanged ideas by drawing on sources that were largely reliable and free from any commercial agenda or political corruption. These meetings were not pre-scheduled events but organic moments in social spaces such as salons and coffee bars. Engaging in a form of deliberative democracy citizens had a range of factual information at their disposal. In Habermas’s view, this constituted an idealised site – a public sphere – where citizens could participate, at length, to form (and reach) a rational consensus on the prevailing issues of the day.

As societies became more modern and industrial, mass production opened up the opportunities for media (at this point primarily newspapers) to reach a far wider audience and, importantly, to generate healthy profits for the rich and corporate minded. This triggered, in Habermas’s thesis, the decline of the public sphere. When society reached a more advanced stage of industrialisation in the mid-twentieth century, capitalism was in full flow and a corporate culture had taken control. The mass media (at this point newspapers, magazines, radio and the early years of television) had become more factually dubious and politically motivated. A wider communication crisis had also engulfed societies with the rise of the public relations and advertising industries. For Habermas, these pernicious industries wielded considerable influence over the kind of mass media that would be produced and fostered a more trivial and commercially motivated public sphere. No longer publicly meeting to deliberate at length on the burning issues of the day, citizens instead were fast becoming private consumers: passively watching, reading and listening to information in their own homes, much of it entertainment-based, on television, radio and print media. The mass media, in short, had become the public sphere but one that fell considerably short of the idealised site Habermas had envisaged happening centuries ago.

Before we start to untangle the complicated economic, social and political forces that shape television journalism today we must recognise that Habermas’s public sphere captures what is democratically possible (and for some even desirable) from mass media. As a normative theory the public sphere reflects a mythical time and idealised space, a benchmark for assessing whether the conditions for sustaining a healthy democratic culture and vibrant citizenship are being met. Television, of course, was still in its early days when Habermas’s book was first published in 1962. As Hallin (1994: 2) has noted, Habermas’s ‘account of the later history of the public sphere is extremely thin. He jumps abruptly from the salons of the eighteenth century to the mass culture of the 1950s’. Since then television has grown into a complex and fragmented beast, the most significant and consumed medium in many countries, representing ‘the major institution of the public sphere in modern society’ (Dahlgren 1995: x). Across many regions of the world, it has ‘been essential to the experience and practices of citizenship for five decades or more’ (Gripsrud 2010: 73).

While news and current affairs is not the only genre to experience and practise citizenship on television (Stevenson 2003; Wahl-Jorgensen 2007), it is what best captures the kind of public sphere Habermas imagined centuries before. The genre of television journalism today, of course, stretches well beyond conventional evening bulletins or serious current affairs programming. From afternoon chat shows like Loose Women in the UK to View in the US (which featured the first ever daytime television interview with an American President, Barack Obama, in July 2010), Michael Moore documentaries such as Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 to comedy news like The Daily Show in the US or 10 O’Clock Live in the UK, television journalism has become an increasingly hybrid genre. In what some might call a postmodern development, conventions from a range of genres have been spliced together to form new ways of informing, engaging and entertaining viewers about politics and public affairs (Jones 2005, 2009). Chapter 4 weighs up the relative merits of new television journalism formats and asks how much of a contribution they have made to rejuvenating the television news genre.

When compared to other forms of journalism, television news and current affairs operate on a medium where their consumption is deeply ingrained in everyday life and culture (Hart 1994; Silverstone 1994). While newspapers may conveniently fall through the letterbox, magazines can be religiously purchased each week or news delivered at the touch of a button online, none of these media are utilised with the same degree of routine as watching television. Ethnographies of media use have shown how the television set is strategically placed at the centre of people’s social living space (McKay and Ivey 2004). And in more recent years, television sets have moved beyond the living room. As a result, multiple televisions shape not only the layout of a living room, but also increasingly the bedroom, kitchen, garage and, for those lavish enough (to afford it), the bathroom. Television, in this sense, is more than part of the furniture: it is part of the family home, invited into every room and engaged with at any given opportunity. In pubs and clubs, gyms and health spas, libraries and waiting rooms, trains and planes, a television screen – often showing a rolling news channel – will never be far from people’s view. Indeed, apart from sleeping and working, surveys show watching television is what occupies most people’s time and energy. As Briggs has put it, television viewing is

utterly ubiquitous in Western societies, part of the fabric of our everyday lives, a common resource for storytelling, scandal, scrutiny, gossip, debate and information: always there, taken for granted ... Television, both as a communicator of meanings, and as a daily activity, is ordinary. (2009: 1; original emphasis)

Television, then, is a one-stop-shop for information, education and entertainment programming.

While the rise of dedicated 24-hour news channels over the last decade or so (see Chapter 3) has made information and education services more widely available, most of the time it is entertainment channels that are most desired. Soap operas, football games, reality game shows, films and other popular programming are what dominate television schedules. Towards the end of the last millennium this was exacerbated by the arrival of multi-channel television that was able to broadcast a plethora of new programming around the clock.

But, as Chapter 7 illustrates, the actual diversity of television schedules can often be related to the level of public and private broadcasting provision within nation states. While many countries have increasingly moved towards the highly commercialised US model of broadcasting (Gripsrud 2010), there is resistance still being shown in some nations who remain proud of their public service traditions and are unwilling to let an unfettered market power dominate and state control diminish. In Europe, where an infrastructure of public service remains relatively strong, this has been difficult to withstand (Cushion 2012). As a result of the commercial media market being liberalised in the late 1980s and 1990s, it is today possible to access hundreds of channels via cable and digital platforms (Chalaby 2009). Rather than fuelling a more diverse television culture, however, systematic studies of television schedules have found these tend to rely on cheap, populist programming – imported shows (usually US in origin), Hollywood films, light entertainment, low-budget shopping channels – to make up the vast majority of what appears on screen. While there are some highly valued cultural and arts channels it has been observed that, in a European context over the last two decades, ‘unashamedly commercial television was on the offensive and conquered large parts of the viewing audiences’ (Gripsrud 2010: 81).

In this increasingly populist and crowded multi-channel television culture, then, how much priority is given to television news journalism?

Scheduling wars: locating television news in an increasingly entertainment-based medium

Most striking, for news and current affairs journalism in the multi-channel era, is the abundance of dedicated 24-hour news channels that have sprung up over the last decade or so (Cushion and Lewis 2010). For many viewers rolling news channels have become a familiar and accessible part of cable and digital television packages. Different packages make it possible to access a range of international, national and local stations, not just from their own countries but also from different regions of the world (Rai and Cottle 2010). In the UK, it is not uncommon – with even a basic cable Freeview package – to tune into English-language versions of BBC World News, Russia Today, Fox News, Sky News, CCTV and Euronews, amongst many more, without paying any subscription charge. While the international news channels can attract millions of viewers around the world, the audience size for some national 24-hour news channels can be relatively low. Moreover, rolling news channels tend to be watched by media, business and political elites (Garcia-Blanco and Cushion 2010; Lewis et al. 2005). Rolling news, nevertheless, has extended the menu of journalism on television and – as argued in Chapter 3 – has had a broader impact on the conventions and practices of television journalism.

Notwithstanding the contribution made by 24-hour news channels, television journalism is most regularly consumed on terrestrial or free-to-air channels. But these channels, such as BBC1 and ITV in the UK, are not genre specific: they offer up a range of programming throughout the day. Within the UK, the free-to air channels are required by law to run a quota of public service programming in their schedules. In this respect news and current affairs are seen as being synonymous with public service commitments (a point returned to in a moment). At the same time, the quota of programming legally imposed on channels operating within a public service framework includes balancing out the genres beyond news such as children’s programming, the arts and religious affairs. The rest of the time they are free to run more preferred (since they are more popular and advertiser friendly) entertainment and sports programming. In balancing these genres, the priority placed on news and current affairs can be assessed by examining where they appear in television schedules.

Television schedules, for the most part, tend to be ignored by scholars (Ellis 2000). Instead it is the advertisers and programme makers who pay most attention to them since these are used to generate revenue or capture the largest slice of the audience. In our multi-channel era, however, scheduling has perhaps become even more important. With so many channels to choose from, now more than ever a routine relationship with viewers needs to be forged in order to cultivate consumer loyalty. For John Ellis, television schedules are ‘the locus of power in television’ (2000: 134), revealing much about how programming is prioritised across different channels. If we examine television journalism in this context it can be observed that news and current affairs plays an important role in the schedule but one that, in more recent years, appears to be second best to other television genres. Apart from breaking news stories (such as the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and 7/7 which, in the UK, were broadcast live on terrestrial channels), news and current affairs programming seems to be scheduled outside of prime time. The peak viewing hours – broadly 7pm–10pm in most countries – tend instead to be reserved for more popular, light-hearted entertainment.

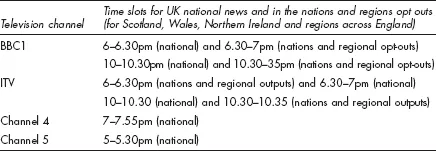

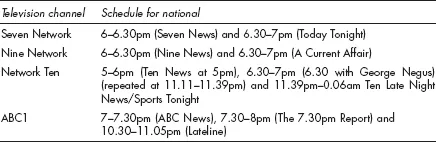

A quick glance at the UK’s, Australian and US’s evening television news (see Tables 1.1–1.3) time slots indicates that the free-to-air bulletins avoid, for the most part, prime-time scheduling. While it would be misleading to suggest these bulletins represent a complete picture of news and current affairs on television in each country, they nonetheless usefully demonstrate where television journalism routinely features in the prime-time schedule. Apart from ABC1 in Australia, television news across the three countries is scheduled either before 7pm or after 10pm. While there is some variation in Australia and the UK, it is noteworthy that many rival television channels routinely schedule their bulletins against each other. This is most obvious in the US where the three big networks all provide news at the same time – namely 6.30–7pm – with each emphasising the role of the anchor to brand its own identity. In one sense, this may reflect when television news is most likely to be consumed. It can, however, also be viewed as a highly strategic move on the part of the broadcasters concerned: if each one runs news and current affairs at the same time, no one station will suffer a dip in ratings (and thus ‘take a hit’ from lost advertising revenue). Either way, it reduces pluralism in television news since viewers are not able to routinely watch the day’s events from a variety of perspectives. There is, however, more pluralism in the Australian and UK schedules – where a stronger public service culture exists – compared to the US which is more commercially orientated (Cushion 2012).

Table 1.1 Time slots for the evening news bulletins on UK terrestrial television channels

Table 1.2 Time slots for the evening news bulletins on Australian terrestrial television channels

Table 1.3 Time slots for the evening news bulletins on US terrestrial television channels

If scheduling is sometimes overlooked in academic circles this is not the case within the industry. In the UK the rescheduling of the BBC1 and ITV evening news bulletins that took place at the end of the last millennium was to generate considerable publicity. Since both channels were legally required to air television news as part of their routine schedules, ITV requested permission to move its late night bulletin from 10pm to 11pm in 1999 on the basis that it wanted to run more entertainment programming and screen films uninterrupted (having previously had to break for the Ten O’Clock News). While this was accepted by the then regulator, the Independent Television Commission (ITC), audiences rapidly declined within a year and ITV was asked to schedule its nightly bulletin at an earlier time. Returning to its 10pm slot, ITV was then faced with competition from the BBC who had also requested whether it could move the nightly bulletin from 9pm to 10pm. This decision, in the words of BBC1’s controller, was to allow ‘us to open up our schedule to show more quality programmes at 9pm, including new drama such as Crime Doubles and Clocking Off and strong documentaries like Blue Planet’ (cited in BBC News 2001). Having enjoyed a 30-year stint at 9pm, television news had ceded its prime-time slot for more entertainment genres.

A scheduling war soon broke out between ITV and the BBC. The latter believed, in a multi-media and online age with rolling news channels, that it would not impact on news audiences overall. ITV, meanwhile, argued the BBC’s move to 10pm reflected ‘a major abdication of the corporation’s public service responsibilities’ (cited in BBC News 2001). In the years following the BBC has attracted a greater share of the audience than ITV and the news slot has remained on the schedule at 10pm. ITV, however, never settled on a regular slot and has struggled to sustain consistent viewing figures. While it agreed initially to a 10pm slot with the ITC for three days of the week, this was subsequently renegotiated to a more permanent time of 10.20pm during the week and then moved again to 10.30pm a year later. In 2008 it returned to 10pm, but has struggled to compete with BBC1’s 10pm news. A McKinsey review into the future of ITV news for the Chief Executive, Adam Crozier, in November 2010, reportedly recommended ITV’s national news (and its regional 6pm service) should be re...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The role of news in television culture: current debates and practices in contemporary journalism

- Part I: History and Context

- Part II: Trends in Television Journalism

- Part III: Journalists and Scholars

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Television Journalism by Stephen Cushion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Journalism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.