- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Social Science Research

About this book

The ability to read published research critically is essential and is different from the skills involved in undertaking research using statistical analysis. This New Edition of Thomas R Black?s best-selling text explains in clear and straightforward terms how students can evaluate research, with particular emphasis on research involving some aspect of measurement. The coverage of fundamental concepts is comprehensive and supports topics including research design, data collection and data analysis by addressing the following major issues: Are the questions and hypotheses advanced appropriate and testable? Is the research design sufficient for the hypothesis? Is the data gathered valid, reliable and objective? Are the statistical techniques used to analyze the data appropriate and do they support the conclusions reached?

Each of the chapters from the New Edition has been thoroughly updated, with particular emphasis on improving and increasing the range of activities for students. As well, coverage has been broadened to include: a wider range of research designs; a section on research ethics; item analysis; the definition of standard deviation with a guide for calculation; the concept of `power? in statistical inference; calculating correlations; and a description of the difference between parametric and non-parametric tests in terms of research questions.

Understanding Social Science Research: An Introduction 2nd Edition will be key reading for undergraduate and postgrduate students in research methodology and evaluation across the social sciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Social Science Research by Thomas R Black in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Wissenschaftliche Forschung & Methodik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Evaluating Social Science Research: An Overview

Social science research involves investigating all aspects of human activity and interactivity. Considering traditional academic disciplines, psychology tends to investigate the behaviour of individuals, while sociology examines groups and their characteristics. Educational research can be viewed as an endeavour to expand understanding of teaching/learning situations, covering the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains, thus drawing upon the perceptions of both psychology and sociology. Many other disciplines such as nursing and health-related studies, business and economics, political science and law, address analogous issues and employ many of the same research tools. Ideally, the research community should be able to address itself to general, global questions, like what enhances learning in primary school, what contributes to poverty, why individuals engage in crime, which would in turn generate a set of specific research questions. To resolve such issues would require researchers to choose the appropriate research tool or tools for the chosen specific question(s). Individual researchers (or teams) would select an aspect of the problem of interest that was feasible to tackle with the resources available. Their contribution would then be added to the growing body of knowledge accumulating through the combined efforts of the research community. To a certain extent, this does happen, but unfortunately many of the disciplines in the social sciences seem less able to achieve such a coherent approach to research than some other academic areas.

This shortcoming stems at least partially from the fact that carrying out social science research involves considering many more variables, some of which are often difficult if not impossible to control. This is unlike research in the natural sciences which commonly takes place in a laboratory under conditions where control over potentially contributing factors is more easily exercised. Second, there is less widespread agreement about underlying theories and appropriate methods for resolving issues in the social sciences than in many natural science disciplines. Consequently, a wide variety of measuring instruments, research tools and approaches are employed, some of which may seem unnecessarily complicated. These complexities and idiosyncrasies of social science research present a challenge for the person new to the scene.

Adding to the difficulty of extracting the most out of published research are the various ‘schools of thought’ relating to social science research. On a more public level, note the dissonance between clinical and experimental psychologists. In some academic departments, staff who ‘use statistics’ have not been spoken to by their colleagues who ‘never touch the stuff’ for years. On a more intellectual level, there has been considerable discussion about such schisms. Cohen and Manion (2000) present a comprehensive discussion leading to the classification of two research ‘paradigms’, though not all researchers conveniently admit to belonging to one or the other, or even fit the categories. Historically, these derive from objectivist (realism, positivism, determinism, nomothetic) and subjectivist (nominalism, anti-positivism, voluntarism, ideographic) schools of thought. Briefly, as Cohen and Manion (2000: 22) note:

The normative paradigm (or model) contains two major orienting ideas: first, that human behaviour is essentially rule-governed; and second, that it should be investigated by the methods of natural science. The interpretive paradigm, in contrast to its normative counterpart, is characterized by a concern for the individual. Whereas normative studies are positivist, all theories constructed within the context of the interpretive paradigm tend to be anti-positivist.

Though the anti-positivists level the criticism that science tends to be dehumanizing, it can be argued that science (or more appropriately, a scientific approach) is a means, not an end; with it we can both better understand the human condition and predict the consequences of action, generalized to some degree. How this understanding is used or what action is taken will be based upon values, the realm of philosophy. Thus it may not be science that de-personalizes, but the values that the people who apply it have; thus if there is any corruption of the human spirit, it lies in beliefs and human nature, not in a scientific approach. To recall an old ditty based upon a murder case in New England in 1892,

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks

And when she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

And gave her mother forty whacks

And when she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

To say that science is evil is like convicting the axe, instead of the murderer who used it as a tool for the destruction of human life.

Science is no more susceptible to abuse in the form of depersonalization and human degradation than any other competing intellectual endeavour. We have seen, and still see, wars in the name of God, carried out by virtually every major religion in the world, most of which have a major tenet against killing. There has been and will be oppression in the name of political systems that purport to represent and protect the masses, resulting in everything from dictatorships of the proletariat under communism to restrictive voting practices to ‘protect’ so-called democratic societies. Science or a scientific approach in viewing the world, like religion, political theory or humanistic psychology, is a means to understanding, and is depersonalizing in the study of people only if the social scientist wants it to be.

One goal of scientific research is to be self-policing through rigour and consistency of practice. This is necessary if the conclusions drawn at the end of a piece of complex research are going to be valid and replicable. Logical consistency from one stage to another, combined with reliable procedures, are essential. While achievement of this goal through so-called good practice is implicit in any study, scientific research is just as prone to bias and/or poor practice as any approach. The unresolved case of Cyril Burt’s studies of identical twins comes to mind, unresolved in the sense that there is not conclusive evidence that he falsified his data, but there is strong statistical evidence that he did. As Blum and Foos (1986) note, scientists are human beings and susceptible to common foibles including stupidity and dishonesty. They summarize their view of the academic world as follows:

Whereas some scientists espouse the view of self-correcting mechanism whereby scientific inquiry is subject to rigorous policing, others believe that academic research centers foster intense pressure to publish, to obtain research and renewal of grants, or to qualify for promotion. Still others believe that finagling is endemic and that public exposure is to be continually encouraged.

This does not mean that there is widespread fraud and that reading research reports is like trying to buy a used car from a politician. Evaluating research requires a more measured approach: many reports will have faults, most will provide some valuable insights, but judging the validity of these will require knowing what to look for.

There are limitations to both ‘paradigms’, particularly when applied in isolation from one another. Quantitative research is quite good at telling us what is happening, and often qualitative studies are better at determining why events occur. When poorly conducted, normative (quantitative) studies can produce findings that are so trivial as to contribute little to the body of research. On the other hand, interpretive (qualitative) studies can be so isolated, subjective and idiosyncratic that there is no hope of any generalization or contribution to a greater body of knowledge. When ideologies are taken to less extremes, it can be said that the two paradigms complement each other, rather than compete. It often takes both to answer a good question comprehensively. To choose one as the basis of research prior to planning may be a philosophical decision, but it also could be likened to opening the tool box, choosing a spanner and ignoring the other tools available when faced with a repair task. To reject the findings of researchers who appear to subscribe to a supposed opposing paradigm is to ignore a considerable body of work. Cohen and Manion (2000: 45) summarize the position nicely when closing their discussion on the subject:

We will restrict its [the term research] usages to those activities and undertakings aimed at developing a science of behaviour, the word science itself implying both normative and interpretive perspectives. Accordingly, when we speak of social research, we have in mind the systematic and scholarly application of the principles of a science of behaviour to the problems of people within their social contexts; and when we use the term educational research, we likewise have in mind the application of these self same principles to the problems of teaching and learning within the formal educational framework and to the clarification of issues having direct or indirect bearing on these concepts.

The particular value of scientific research in the social sciences, as defined above, is that it will enable researchers and consumers of their research to develop the kind of sound knowledge base that characterizes other professions and disciplines. It should be one that will ensure that all the disciplines which are concerned with enhancing understanding of human interaction and behaviour will acquire a maturity and sense of progression which they seem to lack at present. It also does not limit researchers in their choice of research tools, but does demand rigour in their application.

This book will address the issue of evaluating the quality of a major subset of social science research: those involving various forms of observation and measurement (some of which will employ statistics as a decision-making aid) as reported in research journals, conference papers, etc. It is felt that this covers some aspect of the majority of all social science research since most involves collecting data of one form or another, and all data gathering should be well defined and verifiable (Blum and Foos, 1986). While this begs the issue as to which ‘paradigm’ is being employed, it does mean that the criteria and evaluation approaches described here will apply to some aspects of almost any study that collects data, quantifiable or not, though the emphasis is on quantitative research. Consequently, this book does leave out philosophical studies, assuming they do not refer to observation- or measurement-based research.

There are two practical reasons for emphasizing this aspect of social science research. The first is to assist readers in overcoming the problem of interpreting existing publications containing numerical data and statistical analysis. The second is to assist designers of research, since the cause of much low-quality social science research (and not just statistically based studies) is often rooted in problems of measurement and data collection. Too often, new researchers base their techniques unquestioningly upon the practices of others. They read the research reports and journal articles and assume that if they are published, they must have followed acceptable procedures. This is not a sound assumption in an age when academics suffer from the ‘publish or perish’ syndrome, and not all journal referees are equally proficient in separating the wheat from the chaff.

Having made what may seem to be a somewhat cynical, if not damning, comment on the editorial capabilities of research publications, one must accept that it is not a trivial task to analyse a research paper critically. There can be errors of omission as well as faulty logic and poor procedure. Many of these must be inferred from reading a written discourse and their relative severity weighed against some vague standard of acceptability. Consequently, it must be realized that it is very unlikely that a consumer of research will become highly proficient at evaluating studies just by reading this book in isolation. Like most complex skills, such proficiency will be acquired through practice and application to a variety of situations, and thus there is a considerable number of activities built into this material. As with most higher level intellectual skills, the acquisition of these can benefit from discussions and interaction with fellow researchers. Therefore, most of the activities will focus on the discussion and evaluation of research papers; thus it would be desirable to have a forum in which to defend and justify your position, in order to ensure your logic and criteria are sound. This can be done in a class, tutorial or computer-based classroom, but it could also be carried out by your discussing an article with a friend.

In general, the consumer of research reports should learn to be critical without being hypercritical and pedantic, able to ascertain the important aspects, ignore the trivia and, to a certain extent, read between the lines by making appropriate inferences. The ability to identify true omissions and overt commissions of errors is a valuable skill. It is not so much a matter of right and wrong, but one of considering the relative quality. No research carried out and reported by humans is going to be perfect, and at the other extreme, little published material will be totally useless. Therefore, as consumers, we must be able to ascertain the worthwhile and ignore the erroneous without rejecting everything.

RESEARCH DESIGNS

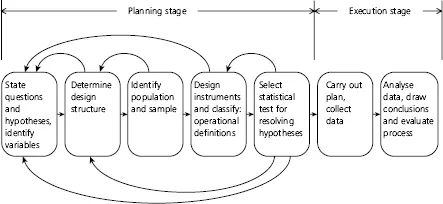

Regardless of which research approach is eventually chosen, all research endeavours have some traits in common. This is based on the assumption that the primary purpose is to expand knowledge and understanding. It is doubtful that an endeavour to justify a stand regardless of the evidence available can be considered research: these are the domains of irrational opinion, beliefs and politics. Figure 1.1 outlines the key components of almost any quantitative research activity, though the actual order of events may vary somewhat from the sequence shown and each step may be visited more than once, the researcher reconsidering a decision having changed his/her mind, or wishing to refine a point.

Beginning at the left, an overall question will have arisen in the potential researcher’s mind, based on previous experience(s), reading and/or observations. For example, what enhances learning, why do people forget, what social conditions contribute to crime, what influence on attitudes does television have?

For a researcher to begin a project with no question formulated but with a research approach already chosen, like a case study, survey, statistical model, etc., is, as suggested earlier, roughly equivalent to opening one’s tool box, grasping the favourite spanner, and dashing about to see what needs fixing. On the other hand, this does not mean that the statement of the question should be so restrictive as to hamper the quality of the research by placing an unchangeable constraint, but a question does need to be identified to provide a touchstone for subsequent steps in the process. In any case, one would expect when reading a research paper to find a statement of the overall question being addressed, or the question whose answer to which the researcher intends to have his/her results contribute.

FIGURE 1.1 Stages of design and carrying out a stud...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- 1 Evaluating Social Science Research: An Overview

- 2 Questions and Hypotheses

- 3 Research Designs and Representativeness

- 4 Data Quality

- 5 Descriptive Statistics: Graphs and Charts

- 6 Descriptive Statistics: Indicators of Central Tendency and Variability

- 7 Statistical Inference

- 8 Correlational Studies

- 9 Parametric Tests

- 10 Non-parametric Tests

- 11 Controlling Variables and Drawing Conclusions

- 12 Planning Your Own Research

- Appendix A Sample Article

- Appendix B An Introduction to Spreadsheets

- References

- Index