![]()

Part I Preparing for Supervision

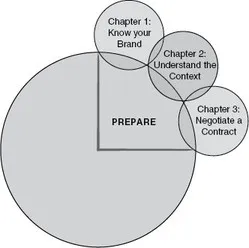

In Part I we consider what needs to be in place in order to establish an effective and ethical basis for CBT supervision (CBTS). This is the ‘Prepare’ phase of the PURE Supervision Flower and focuses on the first three petals, as shown below:

Figure 2 The PURE Supervision Flower: Prepare

Reading this section and working through the various exercises in these first three chapters will enable you to identify, plan for, and work effectively with those factors that provide the foundation for an effective working relationship that will meet your supervisees’ learning and development needs.

![]()

One Know your Brand: Identifying your Position on the CBT Landscape

Learning objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the learning activities provided, you will be able to:

- Better understand the beliefs and values that you bring to CBTS.

- Describe your distinctive ‘brand’ of CBTS.

- Apply methods for identifying and critiquing the ways in which your beliefs and values shape your delivery of CBTS.

Introduction

Contemporary CBT is not so much a single school of therapy as a broad, emerging landscape of theories, models and interventions that is ‘full of controversies’ (Westbrook et al., 2012: 1). Because of this, claiming to be a CBT practitioner reveals less about an individual’s method and style of working than might initially be assumed. Practitioners need to position themselves within the range of possible CBT approaches in order to provide a theoretically coherent and technically competent service to their clients. The choice a practitioner makes about where they position themselves on that landscape will reflect beliefs about the nature of human distress, assumptions about how therapy facilitates change, and a range of personal and professional values. This is equally the case for CBTS, where the supervisor’s beliefs and values provide a foundation for what is offered and permeate the work that unfolds.

The aim of this chapter is to help you clarify, reflect upon and critique what you bring to CBTS in terms of your beliefs and values. As a basis for developing your effectiveness as a supervisor, reading this chapter will help you clarify where you situate yourself within the theoretical and technical landscape of CBT and define your ‘brand’ of supervision. By becoming clearer about these factors, the aim is to help you gain clarity about the nature of what it is you offer, those supervisees who are most and least likely to benefit from that offer, and the implications of this for the clients whom you seek to serve through your work together.

Identifying your beliefs about CBT

When introducing supervisees to what may seem like an unfamiliar way of working, or perhaps to a new way of being supervised, Liese and J. Beck (1997) propose that it is helpful for CBT supervisors to assess for the presence of any beliefs about CBT that may interfere with (or, we might add, help) therapeutic practice. Friedberg et al. refer to the importance of ‘Harvesting open and flexible attitudes’ in supervisees (2009: 111). They cite Freiheit and Overholser (1997), who have observed that therapists’ preconceived ideas impact their degree of receptiveness to novel information in critical ways. Specifically, attitudinal biases can fuel selective attention such that supervisees may devote more energy to identifying the flaws in an approach rather than learning how to deliver it.

In a similar vein, Liese and J. Beck (1997) highlight that supervisees may adhere to common misconceptions about CBT that have arisen over the course of its history, such as a belief that CBT underplays the importance of emotions or the therapeutic alliance. In our experience, therapists do indeed bring to the practice of CBT a range of cognitions, some of which are more helpful (and more accurate) than others. Reading the list of beliefs about CBT that we often encounter, consider which of these have been prevalent among those whom you supervise (or indeed those you might hold yourself) and how they may have impacted the work that followed:

- CBT fits clients to models.

- CBT is evidence-based.

- CBT aims to reduce negative thinking and increase positive thinking.

- CBT is concerned with the ‘here-and-now’ and is less concerned with the client’s developmental history.

- CBT does not work for clients with complex needs.

- CBT is protocol-driven.

- CBT is primarily concerned with teaching clients techniques.

- CBT can obtain symptom relief but is unlikely to produce enduring personality change.

At the start of any supervision engagement we recommend that supervisors talk openly about thoughts, assumptions and beliefs that therapists may be bringing to their CBT practice and also how these might shape their expectations of supervision as a learning environment. For example, if a supervisee believes that the field of CBT offers protocols for every clinical presentation which deliver clear instructions about which intervention should be used and when, this is likely to create an expectation that the supervisor will provide didactic and piecemeal instructions. Alternatively, if a therapist believes that CBT principally comprises the delivery of a series of techniques, this may create an expectation that the supervisor will focus predominantly on the teaching of specific cognitive and behavioural strategies. Confusion may follow when the supervisor insists on devoting time to assessment and formulation, and prevents the therapist from ‘leaping’ into interventions before sufficient clinical data have been obtained.

The various traditions that now comprise the field of CBT adhere to different beliefs about the nature of human distress and how best to bring about change. For example, the so-called first, second and third generations of CBT (see Hayes, 2004) differ conceptually in their views on the extent to which behaviour or cognition, and acceptance or change methods should be privileged when working to enhance clients’ well-being. These differing perspectives provide orienting contexts that have significant implications for the way in which therapist learning and development is undertaken. Thus, how CBTS is delivered in the context of a randomized controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of a specific treatment protocol derived from a second-generation (cognitively focused) approach will look very different from the style and content of supervision provided by a therapist who is offering Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in a drug and alcohol service. It follows, therefore, that as supervisors, it is just as important to work towards uncovering our own beliefs and assumptions about CBT and its relevance to our clients, as it is helping our supervisees uncover theirs.

In Learning Activity 1.1 we invite you to identify those beliefs and assumptions that are relevant to how you approach your work as a CBT supervisor. How do they shape what therapists experience when they receive supervision from you?

Learning Activity 1.1 What type of CBT therapist are you?

Take some time to consider your own beliefs about CBT. To what are you referring when you use the term ‘CBT’? On which part of this broad conceptual paradigm are you focusing? Based on this definition:

- What do you value most about CBT?

- What do you value least about CBT?

- If you, or a member of your family needed therapeutic support, would you recommend CBT or not? (If so, why? If not, why not? If you are unsure, what are the factors you would need to take into account in order to reach a decision?)

Then consider:

- What are your beliefs about the causes and maintenance of human distress?

- What are your beliefs about therapeutic change? How do you know when it has been achieved? What does it look like?

- What are your beliefs about pathways to change? By what mechanisms or methods do you believe this occurs?

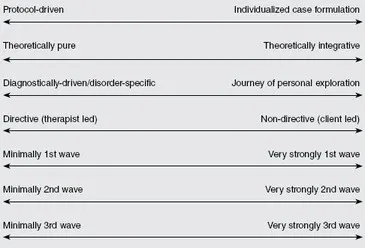

Having spent some time sifting through your answers, look at the continua below. Place a cross on each one according to your own understanding of CBT when you practise this as a therapist. Notice if there are any discrepancies between the type of CBT you practise and the type of CBT you supervise. Notice also if there are any differences between the kind of CBT you offer (as a therapist) and the kind of CBT you would like to receive if you were a client.

It is important to note that there are no right or wrong responses to this exercise. However, where you and your supervisees position yourselves on these continua will have implications for how supervision unfolds, potentially influencing the ease with which you can use different supervision interventions. Your responses may also provide important information on those whom you may be best and least equipped to supervise.

The role of values in CBT supervision

So far we have made the case that an essential starting point in supervision is to enhance awareness – in ourselves and our supervisees – of the beliefs to which we subscribe when we look at our clients’ needs through a CBT lens. However, the approach taken will also be informed by a supervisor’s values.

Values are inherent in all helping relationships and are closely associated with our goals for client work and the interventions we employ in the service of client change (McCarthy Veach et al., 2012). Supervision is also a value-laden activity, shaping the learning environment that the supervisor seeks to offer and serving as a filter for the educational and evaluative methods employed (Nadelson and Notman, 1977).

Despite the dearth of studies examining the influence of values on the content and process of supervision (McCarthy Veach et al., 2012), initial investigations point to the importance of supervisor values as a mediating variable on therapist development. Buckman and Barker (2010), for example, found that the philosophical orientation of the supervisor had an influencing effect on the preferred theoretical orientation of trainee therapists. Multicultural models of supervision have also emphasized the mediating impact of values (see Garrett et al. (2001), who recommend that supervisors and supervisees discuss their respective beliefs about human nature, social relationships and human behaviour in order to identify and address areas of conflict that could arise). Abeles and Ettenhofer (2008) also highlight that many models of supervision are based on Western, Eurocentric and biological perspectives, with all the embedded values to which these worldviews give rise. In such a context, there is the potential for supervisors to adversely affect the learning and development of their supervisees (and perhaps also the well-being of their supervisees’ clients) by failing to attend to differences in value systems. Without an awareness of the values that permeate our work, supervision runs the risk of being dominated by what Hawkins and Shohet (2012) term our ‘shadow motives’.

The empirical neglect of the influence of values in supervision is perhaps unsurprising given that the concept is rarely operationally defined or underpinned by a consistent typology through which specific, testable hypotheses might be generated (Beutler and Bergan, 1991). Indeed, supervisor values are typically referenced indirectly through terminology such as ‘personality and working style’ (Korinek and Kimball, 2003). However, as Long (2011) observes, many supervisors are instinctively aware that how they practise is closely associated with who they are as human beings. Our values are close to our sense of identity, comprising prized personal beliefs that direct goals and motivate behaviour (Brown and Brooks, 1991), personally or socially-derived ideals about appropriate courses of action (Rokeach, 1973), and criteria that individuals use to select and justify actions and evaluate themselves and others (Schwartz, 1992).

Beutler and Bergan (1991) have defined values as stabilizing rules that provide continuity in both the personal and social domains. The notion of values as ‘stabilizing rules’ can be seen as consistent with the concept of conditional beliefs in CBT; that is, enduring cognitions that we may not have articulated to ourselves or others but which manifest as rules, attitudes and assumptions about self, others, life and the world that govern both our actions and sense of our choices. Derived from experience (often early in life), the beliefs inherited from significant others (such as parents, peers, teachers) and culture of origin, their purpose is to serve as a guide to behaviour that enables adaptive functioning. Such assumptions also define the parameters of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ behaviour, and thus prescribe and proscribe what is acceptable. Examples of such stabilizing (and problematic) rules that are often encountered when working with clients in CBT (and indeed some supervisees) might include: ‘If I make an error it means I am incompetent’, ‘I must always please people to be accepted’, and ‘In order to be of worth, I must be successful in everything that I do’.

Within the CBT movement, one approach that has elevated work on values to the heart of therapy is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., 1999). A central aim of ACT is to enable clients to identify, and behave in ways that ar...