![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTION

1

What We Know about Bullying in Secondary Schools

In a report prepared for the New Zealand Office of the Commissioner for Children, Lind and Maxwell (1996) found that when the secondary school students in their study described the three worst things they had ever experienced, the death of someone very close (a mother or father, brother or sister) was mentioned most often. Being bullied by other students came second.

The waiter’s story

Ask anyone anywhere about bullying, and they will have a story to tell. Each one of these stories tells us a lot about bullying and the pain it causes, and each one of them is unique. These stories have led us to take a long hard look at bullying and how it can be dealt with.

In the midst of writing this book, we visited our favorite cafe in central Wellington. It was a beautiful sunny late afternoon, and we sat outside under an umbrella. When the waiter arrived, Keith was indecisive and, explaining his behavior as a result of the heat and the lateness of the day, he then corrected himself and said, “No, the reason I’m a bit unfocused is that we’re writing a book and we’re just taking a break” The young man asked what the book was about, and Keith told him, “Secondary school bullying.” He referred to a recent case of violent school bullying that had been reported in the newspapers, and the young man responded, “That was nothing. You should have been at my school and experienced my bullying.” When Keith talked about our intention of writing a deep and compelling account of secondary school bullying that also offers solutions, the young waiter wavered between being positive and being dismissive. He had attended a single-sex denominational boarding school in another city. He said that although the school had an anti-bullying policy, a culture of bullying and intimidation flourished there. He described how those who were bullies sat at the back of the class and laughed to themselves, because all the tut-tutting about bullying made no difference at all to what went on in the school. In this young man’s class, there were three particular victims: he is still recovering from his experience of being bullied, one is a drug dealer, and the other committed suicide.

The waiter’s story highlights the fact that when schools pay lip service to an anti-bullying stance, they place their students in jeopardy. The message is very clear: schools have to be totally committed to developing a safe environment. What schools do is more important than what they say, and that is why this book is practical rather than theoretical.

Over the last 20 years, there has been a massive amount of interest in bullying among psychologists and educators, and new and useful insights into this complex behavior are added to this growing body of work every year. Taking into account this collective knowledge, reevaluating the bullying literature, and using our own observations and research, some basic tenets about bullying emerge. These are:

- Bullying is unpredictable behavior that appears to strike without pattern and to become a difficult problem for about one in six students.

- It occurs in all types of schools.

- It is not restricted by race, gender, class, or other natural distinctions.

- It is at its worst during early adolescence.

- There is compelling evidence that the impact of bullying has lifelong debilitating consequences.

This book focuses on bullying in secondary school. For adolescents, one of the most important, urgent and affirming requirements for growth and survival is the need to be part of a group, to be accepted, defined, and mirrored by a cohort of peers. We are focusing on the 12-18 age group, and while bullying occurs before and after this, it is at this time that the pivotal questions, “Who am I?,” “What is the meaning of life?,” and “Where do I fit in?” are asked. It is a time when each child moves toward adulthood, passing through various processes of individuation.

What bullying does at whatever age it occurs is to interfere with normal developmental processes. If children have a smooth passage through adolescence, they are likely to experience a growing awareness that they are part of a community, whereas bullying isolates, excludes, and pushes individuals to the periphery. It is the job of teachers and school administrators to make sure that their students are kept well inside this periphery so that they are able to learn and to develop.

Teachers tend to be very practical. They typically say words to the effect that, “Bullying researchers carry out research and provide interesting information and statistics about bullying. They can tell me more precisely, perhaps, what I already know. What I need to know, however, is what to do in my classroom and school tomorrow to deal effectively with bullying.” With this in mind, our purpose is to provide fundamental information and a new interpretation of bullying behavior, as well as practical and useful strategies and solutions.

The chaos theory of bullying

There is a mass of empirical research that gives us a picture of what bullying is, but every time someone is bullied, it is their story that is important, and the circumstances and context of this particular event.

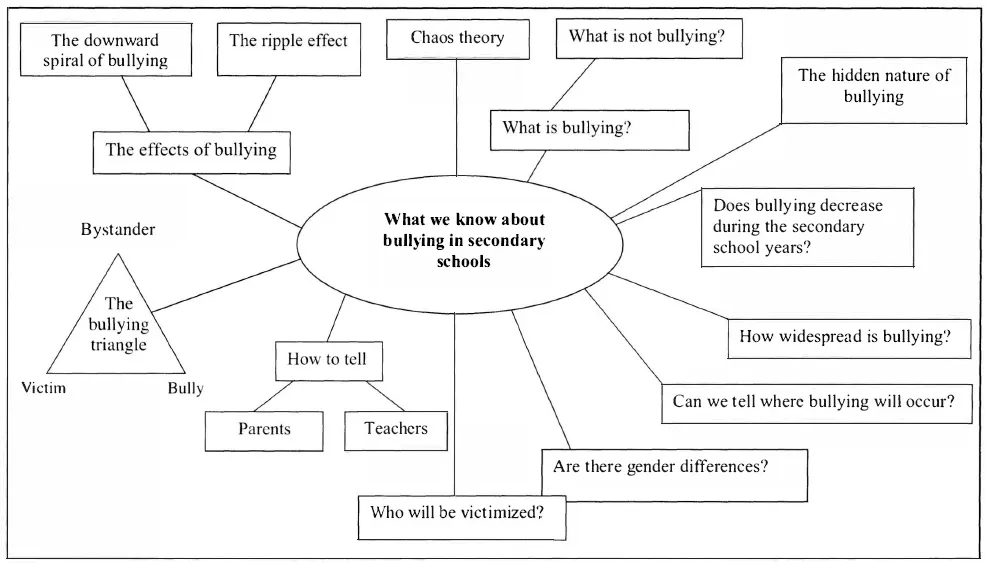

Bullying is a fact of life. Research on bullying tends to focus on rates of bullying, identifying and predicting victims of bullying, and school types or settings where bullying is most likely to occur (Figure 1.1). Empirical evidence is essential and very useful, but isolating and identifying causes will not eliminate bullying; nor can it be used predictively. While we may be able to generalize about the rates, characteristics, and causes, statistical indicators are less important than how bullying affects individuals. In New Zealand, a zealous focus on single-sex boys’ boarding schools in the 1990s had the effect of making other types of schools dismissive of their need to be vigilant about bullying: when high-risk contexts appear to be identified, everyone else puts anti-bullying protection on the back burner. However, being bullied at a coeducational school is every bit as bad as being bullied at a single-sex boys’ school. The message is that all schools should be vigilant.

Bullying is random. What we are arguing is that it can happen to anyone at any time: while there is some predictability, there is also a massive element of chaos. Most research suggests that in year 10, for example, 25 percent of the school population is going to be bullied regularly. But in any sample of students, the victims are unlikely to add up to 25 percent. In one sample, there may be none, and in another, there may be a large number. This brings us back to one of our main points: that however statistical, descriptive, or quantitative research is, it cannot address individual stories, which are the crux of the issue.

What is bullying?

Definition

Bullying is a negative and often aggressive or manipulative act or series of acts by one or more people against another person or people usually over a period of time. It is abusive and is based on an imbalance of power.1

Figure 1.1 What we know about bullying

Bullying contains the following elements:

- The person doing the bullying has more power than the one being victimized.

- Bullying is often organized, systematic, and hidden.

- Bullying is sometimes opportunistic, but once it starts is likely to continue.

- It usually occurs over a period of time, although those who regularly bully may also carry out one-off incidents.

- A victim of bullying can be hurt physically, emotionally, or psychologically.

- All acts of bullying have an emotional or psychological dimension.

Forms of bullying

Bullying can be physical or non-physical and can include damage to property.

- Physical bullying is the most obvious form of bullying and occurs when a person is physically harmed, through being bitten, hit, kicked, punched, scratched, spat at, tripped up, having his or her hair pulled, or any other form of physical attack.

- Nonphysical bullying (sometimes referred to as social aggression) can be verbal and nonverbal.

| (a) | Verbal bullying. This includes abusive telephone calls, extorting money or material possessions, general intimidation or threats of violence, name-calling, racist remarks or teasing, sexually suggestive or abusive language, spiteful teasing or making cruel remarks, and spreading false and malicious rumors. |

| (b) | Nonverbal bullying. Nonverbal bullying can be direct or indirect. Direct nonverbal bullying often accompanies verbal or physical bullying. Indirect bullying is manipulative and often sneaky. |

| | (i) | Direct nonverbal bullying. This includes making rude gestures and mean faces and is often not regarded as bullying as it is seen as relatively harmless. In fact, it may be used to maintain control over someone, and to intimidate and remind them that they are likely to be singled out at any time. |

| | (ii) | Indirect nonverbal bullying. This includes: purposely and often systematically ignoring, excluding, and isolating; sending (often anonymous) poisonous notes; and making other students dislike someone. |

- Damage to property. This can include ripping clothes, damaging books, destroying property, and taking property (theft).

Bullying can be any one of the above or a combination of them.

Bullying is a cowardly act because those who do it know they will probably get away with it, as the victimized person is unlikely to retaliate effectively, if at all, nor are they likely to tell anyone about it. Bullying often relies on those who are marginally involved, often referred to as bystanders, doing nothing to stop it or becoming actively involved in supporting it.

Most bullying is indiscriminate and is not caused by or the result of obvious differences between students: “Victims are not different—the group decides on the difference” (Robinson and Maines, 1997: 51).

Physical bullying often causes visible hurt in the form of cuts and bruises. All bullying causes invisible hurt in the form of internal psychological (or emotional) damage. When the hurt is invisible there is a sense that there is no proof that anything bad has happened.

Victims of bullying may feel alone, angry, depressed, disempowered, hated, hurt, sad, scared, subhuman, trampled on, useless, or vengeful.

At the extreme end of the spectrum of physical bullying is behavior that moves into the realm of criminality and involves the use of weapons. The carrying and use of weapons in schools is a growing phenomenon internationally and is a major cause of concern in American schools in particular. Killings in American high schools in the last few years have occurred across a wide age range. However, a major study of violence in American schools by Kingery, Coggeshall and Alford (1998), that was published before the Columbine and Santee shootings, suggested that the carrying and use of weapons in high schools mostly involved only grade 12 students and was often linked to students who took part in neighborhood violence.

The differences between these findings and the Columbine and Santee attacks should alert us to the fact that statistical results may bear little resemblance to what actually happens. However, research by the US Secret Service on high school shootings, while saying there is no single “typical” school shooter, did suggest that the majority of such students had previously drawn attention to themselves in some way and complained of being bullied (BBC News website, “Education,” July 18, 2001 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/1445005.stm). The carrying and use of weapons can thus be a hidden part of a larger culture in which bullying may be endemic.

While statistical results may give us indications of trends, they can never mitigate against actual bullying events, can never predict who will bully and how, and cannot determine who will be a victim and why.

What is not bullying

In the same way that it is important to be clear about what is bullying, it is also important to be clear about what is not bullying (Sullivan, 2000: 13).

Bullying is hidden, opportunist, mean-minded, and recurrent, and involves an imbalance of power. There are other types of behavior that are sometimes mistaken for bullying but which occur in the open and do not involve an imbalance of power. For example, two individuals (or groups) may get into an argument or fight (verbal or physical) as tempers flare up and things get out of hand. While such conflicts need to be dealt with in schools in a transparent and fair way, they do not constitute bullying. Rather, they are simple cases of conflict.

In some instances, however, individuals or a group set out to create a situation where it appears that those involved have equal responsibility, but this may be part of a plan to discredit a targeted person (or group). They may blame the victim for starting the fight and may even pose as victims themselves to deflect punishment and maintain their hidden status as bullies. It is important that schools are able to distinguish between conflict and bullying, and to see through the web of deceit that typically surrounds bullying.

What we know about bullying

The hidden nature of bullying

One of the major issues to come out of several major research projects (Adair et al., 2000: 211; Smith, 1999: 83, for instance) is that most victims of bullying are reluctant to tell anyone about it. Part of the bullying dynamic is the power imbalance between the bully and victim, which is a guarantee that the bullying is unlikely to be reported. Like other forms of abuse, bullying is hidden. The reasons people do not tell are very complicated:

- Victims are afraid and fear further retribution and harm.

- They think they will be singled out even more, and secretly hope that if they do not tell, the bully may like them after all.

- They do not believe teachers can or will do anything to make the bullying stop.

- They do not want to worry their parents.

- They are afraid that if their parents tell the school authorities, the bullying will get worse.

- Telling on peers is regarded as a very bad thing to do.

- They feel they are somehow to blame.

Research tends to indicate that around 30 percent of victims do not tell (for example, Rivers and Smith, 1994). Differences have been detected in who tells, who is told, and what sort of bullying generally gets reported. For example, Peterson and Rigby found that “reluctance to tell teachers is particularly marked among male adolescents, for whom ‘dobbing’ (an Australian term for ‘telling’) is seriously un-Australian” (1999: 482). Smith and Shu (2000) suggest that students are reluc...