eBook - ePub

Constructing History 11-19

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Constructing History 11-19

About this book

This book describes and exemplifies strategies for teaching history across the 11-19 age range in rigorous and enjoyable ways. It illustrates active learning approaches embedded in pupil-led enquiries, through detailed case studies which involve students in planning and carrying out historical enquiries, creating accounts and presenting them to audiences, in ways that develop increasingly sophisticated historical thinking.

The case studies took place in a number of different localities and show how practising teachers worked with pupils during each year from Y6/7 to Y 13 to initiate, plan and implement enquiries and to present their findings in a variety of ways.

Each case study is a practical example which teachers can use as a model and modify for their own contexts, showing how independent learning linked to group collaboration and peer assessment can enhance learning. Social constructivist theories of learning applied to historical thinking underpin the book, with particular emphasis on links between personalised and collaborative learning and e-learning.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Year 5/6 and Year 7 historians visit Brougham Castle

Hilary Cooper and Liz West

Rationale

These are aims underpinning 2020 Vision (DfES, 2007) which readers may like to use in evaluating our project to:

- communicate orally;

- work as a team;

- evaluate critically;

- take responsibility for learning;

- work independently;

- investigate with confidence;

- be critical, inventive, enterprising.

In this chapter a Year 5/6 class from Lowther Endowed School, a small, rural primary school of four classes in Cumbria, works with a Year 7 (Y7) class from Ullswater Community College, an 11–19 comprehensive school in the nearby town, to which many of the primary pupils will transfer. The secondary school is described in the Ofsted Inspection Report of 2006 as ‘serving the biggest catchment area in England’, which it shares with Cumbria’s only selective grammar school.

Both classes plan group enquiries, which they carry out and record in mixed groups of primary and secondary pupils. They use their findings to create interpretations which they share. Both schools were pleased to be involved in the project. Ullswater Community School is keen to develop links with local primary schools and thought that this might be a model for developing further liaisons. In addition, the head of the history department welcomed the opportunity for a site visit, which he felt might be extended to other Year 7 classes in future, in connection with their study unit on medieval castles, linking local with the national history of the period. The head teacher of Lowther Endowed School said that a visit to Brougham Castle would make an interesting diversion from SATs (standard assessment tasks) preparation, and would fit well into a study of the locality later in the term. Finally, there is generally some concern about the transition from Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3, just as there is from AS level to university (Chapter 5), and the study might to some extent make transition easier for teachers and pupils.

Organization

The head of history at Ullswater Community School and the history teacher involved in the project met with the head teacher and Year 5/6 (Y5/6) class teacher from Lowther School and with us, Hilary and Liz, in December 2007, to discuss which site we might visit and how the project could be planned. Brougham Castle was chosen for the reasons above and because it is a good example of a medieval castle a few miles from each school. Also many localities have a castle so that the ideas we developed could be extended and modified by readers. A brief, tight schedule was agreed, due to time constraints in both schools. We decided that the project would consist of three two-hour sessions and a morning site visit. It would be a challenge, but good discipline, to carry out genuine enquiries within this timescale. Could we do it? If so it would prove the extent to which this is possible.

Planning the project

This led to outline planning for the four sessions.

In the first session we would find out what pupils already knew about castles, then give them key information about Brougham Castle, introduce the concept of enquiries and ask pupils, in groups, to list possible questions to investigate. For practical reasons the two classes would work in their own schools, Hilary working with the Y5/6 class and Liz with the Y7 class.

In the second session, the site visit, the pupils would work in five groups, each consisting of three Y5/6 and three Y7 pupils, collecting ‘evidence’ related to a ‘best fit’ enquiry based on their initial questions. In week 3 they would decide how to present the results of their enquiry and in the final session both classes would meet in the secondary school to share their presentations.

Dates for each session were fixed for the first four weeks of the Summer term 2008. This was because the weather might be more suitable, the castle is not open to the public until April and the deadline for chapter writers’ manuscripts to the editors of the book was the end of May. Hilary and Liz arranged to do a preliminary visit to Brougham with the area officer for English Heritage, on a literally freezing but sparkling day in December. The stone spiral staircase up to the fourth storey of the keep and a visit with 60 children would need thoughtful risk assessment.

So we had some warming soup in a nearby public house and decided on five ‘indicative’ enquiries which would be realistic. The children would certainly begin by asking their own questions, which we would shape to make a ‘best fit’ match with those we had identified, to ensure that it was possible to find relevant information and that the number of enquiries was manageable.

The ‘indicative questions’ were:

- How was the castle defended and where were its weakest points? – clearly a significant question for people over a long period.

- Which was the oldest part of the castle built by Vieuxpoint? Why do you think so? Which part was built by Robert and by Roger Clifford? Why do you think so? – changes over time.

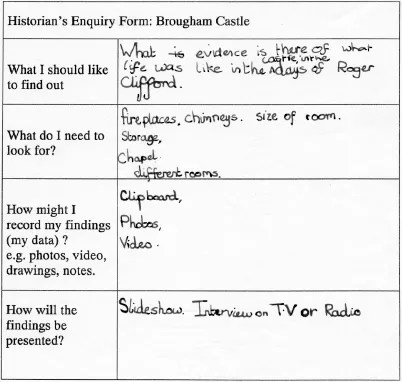

- What evidence is there of what life was like in the castle in the days of Roger Clifford? – deductions and inferences involving historical imagination.

- How can we create a guide which young children might enjoy? – translating key concepts, questions and methods of answering them into appropriate forms of representation so that they can be tackled from the beginning in their simplest form (Bruner, 1963).

- What evidence about locations can we record in order to set a historical ‘novel’ in Brougham Castle? – ‘Academic history produces a “theoretical surplus” which must be seen as the distinctive rationale of researchorientated historical narrative’ (Lee, 2004).

Session 1: framing the questions

History is about asking questions. There sure aren’t a lot of ‘for sure’ facts. (Pupil quoted in Levstik and Barton, 2001)

I went on a coach trip to Dover and it was ever so crowded – and in the middle of it was a castle. Now what on earth did they put it there for? (Student’s landlady)

Year 5/6

Finding out about Brougham: who built it? Why? When?

When I arrived in the Year 5/6 class, unfortunately delayed, the children were listing what they already knew about castles. Analysis showed that most children were aware of characteristic features of castles, and used correct vocabulary: portcullis, drawbridge, moat, turrets and dungeons. They knew that they were made out of stone, were used in battles in the past and are old and usually in ruins. They had some understanding of the concept of a castle, which was a good basis for developing more detailed and contextualized understanding.

Figure 1.1 Example of a chart listing ‘what I know’ and ‘What I’d like to know’ about castles.

Then the pupils were shown a PowerPoint presentation about Brougham Castle

These consisted of aerial views, plans naming the parts and colour coding when each was built and by whom, photographs and artists’ interpretations of what scenes in the castle might have looked like in the past. We discussed why the castle was built, why it was built in this location, which was the oldest part and how you might work that out, and identified the numerous other castles in North Cumbria and Yorkshire shown on a map. (All the material was scanned from Brougham and Brough Castles – English Heritage, 2006). One child saw Lowther on the map and insisted that Lowther Castle was part of the medieval defences which led to an interesting discussion about why castles were built more recently.

Pupils’ questions

Next everyone listed the questions they would like to investigate (Figure 1.1).

The lists of things children ‘wanted to know’ showed a good understanding of what can be investigated from a site and fitted remarkably well with our ‘indicative questions’. They frequently used vocabulary such as attack and defence. Questions were often concerned with which parts of the castle were safest when under attack, which were strongest and which weakest. They wanted to know when different parts of the castle were built, presumably following the PowerPoint information, and the uses of different rooms, for storage, sleeping – were there fireplaces? – how many floors? and how was the accommodation different for different social groups in the castle? Some questions could not be investigated from site evidence: how they dressed, what they ate, how they ‘got around’, what weapons they used and ‘What did they do all day?’

This led to a discussion of how we find out about the past, primary and secondary sources, the fact that some things cannot be known for certain, which is why we need to make ‘guesses’ about them and say why we think that, and that some things cannot be known at all. It was interesting that the three first-year trainee primary school teachers who had volunteered to take part in the project were very concerned that they did not know the answers, saying they would ‘look it all up on the Internet’ and were amazed to learn, when they asked if there would be ‘guides’ at the castle, that the guides would be them. It was quite salutary to realize how vulnerable it can feel not to ‘know’.

Refining the questions

While we were linking the children’s questions to the five we had identified as practicable and sorting out the group to answer each question, the children were given printouts of the slide of the aerial view of Brougham Castle and asked to label and date the parts, which they did surprisingly accurately.

One group, given their reshaped question, felt that their original questions had been disregarded. Not entirely. And I felt that asking them to think of questions had engaged them with the nature of historical enquiry. Historical enquiry, as Collingwood defined (1939), proceeds from specific questions identifying what you know, can ‘guess’ and what you want to know. The job of a historian in the question and answer sequence, Collingwood (1946) said is to ask that the ‘right’ questions, the ones which lead on to the larger complex and do not draw a blank. This explained why some of the questions children wanted to ask at the site would ‘draw a blank’.

How are we going to find out?

Finally the groups having been sorted and each group given their enquiry question each group listed ways in which they thought they might find some of the evidence and how to record it (Figure 1.2).

For example the group investigating defences would look for a ‘ditch’, investigate how the keep was made strong, the size of the windows. The group investigating when each part of the castle was built were given clues about different shapes of windows and added floors.

Figure 1.2 Example of group plans for site visit enquiry, ‘How was the castle defended? Where were its weakest points?’

The group investigating life in the castle realized that they needed secondary sources and started looking at illustrations in books. It was interesting that they focused on information relevant to their enquiry at different periods, while earlier they had been leafing through the books in an unfocused way. They were then told that there were information boards in the castle about each period and it would be a good idea to look at these, then look for evidence in the building which the artist had used in order to create his ‘interpretation’. The group preparing information for young children decided to walk around and record what they thought might interest them. The story-writing group were enthusiastically planning a ghost story, in which Vieuxpoint haunts the Cliffords and considered the kinds of photographs they would take in order to make sure that the scenes looked authentic.

Year 7

Due to the timetable and other considerations for participants, a 50-minute introductory lesson, the si...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction: Constructing history 11 – 19

- 1: Year 5/6 and Year 7 historians visit Brougham Castle

- 2: Bringing the history curriculum to life for Year 8/9

- 3: Towards independent learning in history: Year 10

- 4: Documentaries, causal linking and hyper-linking for AS students

- 5: Advancing history post-16: e-learning, collaboration and assessment

- Afterword

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Constructing History 11-19 by Hilary Cooper, Arthur Chapman, Hilary Cooper,Arthur Chapman,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.