- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this insightful book, one of America?s leading commentators on culture and society turns his gaze upon cinematic race relations, examining the relationship between film, race and culture.

Norman K Denzin argues that the cinema, like society, treats all persons as equal but struggles to define and implement diversity, pluralism and multiculturalism. He goes on to argue that the cinema needs to honour racial and ethnic differences, in defining race in terms of both an opposition to, and acceptance of, the media?s interpretations and representations of the American racial order.

Acute, richly illustrated and timely, the book deepens our understanding of the politics of race and the symbolic complexity of segregation and discrimination.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reading Race by Norman K Denzin,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: reading race

1

The Cinematic Racial Order

Classic Hollywood cinema was never kind to ethnic or minority groups … be they Indian, black, Hispanic, or Jewish, Hollywood represented ethnics and minorities as stereotypes…. Classic Hollywood film [is] ethnographic discourse. (López, 1991, pp. 404–405)

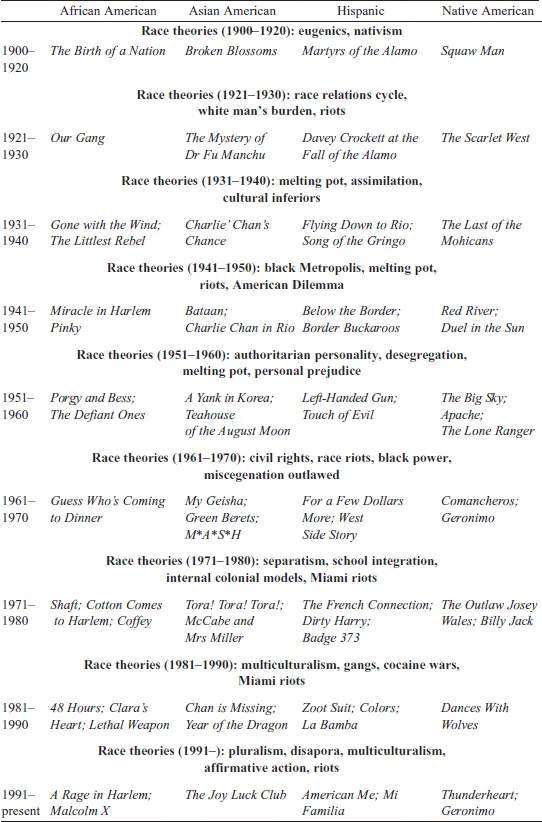

I want to read America’s cinematic racial order through a scene from Spike Lee’s highly controversial 1989 film Do the Right Thing (see Bogle, 1994, pp. 319–320; Guerrero, 1993a, pp. 148–154; Reid, 1997a). I will move backward and forward from this scene, offering a truncated genealogical history of America’s cinema of race and ethnicity (see Friedman, 1991b). I will argue that the films constituting this cinema (see Table 1.1; also the Appendix) can be read as modernist realist ethnographic texts, stories and narrative histories that privilege whiteness, and an assimilation-acculturation approach to the race relations problem in America (see López, 1991, p. 405; Chow, 1995, p. 176; Denzin, 1997, pp. 75–78).1

These films are tangled up in social science theories of race, ethnicity, and the American racial order, including arguments about eugenics, nativism, race-relations cycles, melting pots, authoritarian personalities, internal colonial models, multiculturalism, and theories of disapora and pluralism. As realist ethnographies, as texts that perform situated versions of the racial order, these films have created and perpetuated historically specific, racist images of the dark-skinned ethnic other (see Wong, 1978). This racist imagery extends, like a continuous thread, from Birth of a Nation through Boyz N the Hood. How these films have done this and what its consequences are for race relations today is my topic. But first Lee’s movie.

Doing the Right Thing

In a pivotal moment, near the film’s climax, as the heat rises on the street, Lee has members of each racial group in the neighborhood hurl vicious racial slurs at one another:

Mookie to Sal: (and his Italian sons – Vito and Pino): Dago, Wop, guinea, garlic breath, pizza slingin’ spaghetti bender, Vic Damone, Perry Como, Pavarotti.

Pino to Mookie (and the blacks): Gold chain wearin’ fried chicken and biscuit eatin’ monkey, ape, baboon, fast runnin’, high jumpin’, spear chuckin’, basketball dunkin’ ditso spade, take you fuckin’ pizza and go back to Africa.

A Puerto Rican man to the Korean grocer: Little slanty eyed, me-no speakie American, own every fruit and vegetable stand in New York, Bull Shit, Reverend Sun Young Moon, Summer 88 Olympic kick-ass boxer, sonofabitch.

White cop: You goya bean eatin’ 15 in the car. 30 in the apartment, pointy red shoes wearin’ Puerto Ricans, cocksuckers.

Korean grocer: I got good price for you, how am I doing? Chocolate, egg cream drinking, bagel lochs, Jew ass-hole.

Sweet Dick Willie to the Korean grocer: ‘Korean motherfucker ... you didn’t do a goddamn thing except sit on your monkey ass here on this corner and do nothin’. (see Denzin, 1991a, pp. 129–130)

Table 1.1 The Cinematic Racial Order and American Theories of Race Relations, 1900–2000 (representative films)

Sources: Bataille and Silet, 1985; Bogle, 1994; Guerrero, 1993a; Keller, 1994; Richard, Jr, 1992; McKee, 1993; Boyd, 1997

Race and Ethnic Relations in Lee’s World

Lee’s speakers are trapped within the walls and streets of a multiracial ghetto (Bed-Stey). Their voices reproduce current (and traditional) cultural, racial, and sexual stereotypes about blacks (spade, monkey), Koreans (slanty eyed), Puerto Ricans (pointy red shoes, cocksuckers), Jews (bagel lochs), and Italians (Dago, wop). The effects of these ‘in-your-face insults’ are exaggerated through wide-angled close-up shots. The speaker’s face literally fills the screen as the racial slurs are heard. These black and white, Korean, Puerto Rican, and Hispanic men, women and children exist in a racially divided urban world, a violent melting pot. Here there is little evidence of assimilation to the norms of white society. (There is no evidence of the black middle class in this film.) Complex racial and political ideologies (violence versus non-violence) are layered through subtle levels and layers of sexuality, intimacy, friendship, hate, love, and a lingering nostalgia for the way things were in days past.

Prejudice crosses color lines. But racial intolerance is connected to the psychology of the speaker (e.g. Vito). It is ‘rendered as the how of personal bigotry’ (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 154, italics in original). The economic and political features of institutional racism are not taken up. That is, in Lee’s film, ‘the why of racism is left unexplored’ (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 154, italics in original).

Even as racial insults are exchanged, Lee’s text undoes the notion of an essential black, white, Korean, Puerto Rican, or Hispanic subject. Each speaker’s self is deeply marked by the traces of religion, nationality, race, gender, and class. Blacks and Koreans inhabit an uneasy, but shared, space where, in the moment of the riot, the Korean grocer can claim to be black, not Korean. Lee’s world is a cosmos of the racial underclass in American today. This is a world where persons of color are all thrown together, a world were words like assimilation, acculturation, pluralism, and integration have little, if any, deep meaning. Lee’s people have been excluded from the social, economic, and political structures of the outside white society.

In this little neighborhood’s version of the hood, differences are ridiculed and mocked. Separatism is not valued, although intergroup differences are preserved, through speech, music, dress, and public demeanor. Indeed, like ethnic voyeurs, or middle-class tourists, the members of each ethnic group stare at one another and comment on how the racially and ethnically different other goes about doing business and daily life. These separate racial and ethnic groups are not merging into a single ethnic entity.

Only in a later film, Clockers (1995), will Lee take up the ‘insidious, socially fragmented violence’ (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 159) of the hood films of Singleton, Van Peebles, and the Hughes brothers. Cheap guns, crack-cocaine, gang and drug warfare are not present in Do the Right Thing. But a seething racial rage is, a rage that is deeper than skin color. This is a rage, even when muted, that attacks white racism, and urges new forms of black, Korean, Puerto Rican, Hispanic, and Latino nationalism.

Thus is evidenced a reverse form of ethnic nativism: disadvantaged racial group members stereotyping and asserting their superiority over the ethnically different other. Victims of racial hatred, they reproduce that hatred in their interactions with members of different racial and ethnic groups. The benefits of the backlash politics of the Reagan and Bush years are now evident (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 161). Fifteen years since Reagan came in of playing the race card, fifteen years of neo-conservative racial nativist national politics come home to roost. The nation’s racist, crumbling, violent, inner-city ethnic enclaves have become ‘violent apart-heid environments’ (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 159, italics in original).

And so Do the Right Thing, as realist ethnographic text, marks one ending for one history of the race relations story in America today: that ending that has race riots, and racial minorities attacking one another.2 This ending demonstrates the paucity and tragedy of nativist and liberal assimilationist (and pluralist) desegregation models of race and ethnic relations (McKee, 1993, pp. 360–367). It is as if the clock had been turned back to 1915 and everyone was watching D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation: white men in Klan hoods attacking coons who are sexually threatening the sexuality and lives of white women. The birth of a new racist nation.3 But how to start over?

In the Beginning: Creating a Cinema of Racial Difference

There is no fixed place to start the conjunctural history of America’s cinematic racial order. Even before Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), earlier silent films, including Chinese Laundry Scene (1894), Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903), and A Gypsy Duel (1904), were presenting racist views of American race relations (Guerrero, 1993a, p. 9; Keller, 1994, pp. 10–11), Nonetheless, by the mid-1920s Hollywood had firmly put in place a system of visual and narrative racism (Wong, 1978, pp. 2, 73–75) that privileged whiteness.4 This system solidified what would be a near-century-long version of racial and ethnic stereotypes. These stereotypes would be fitted to the cinematic representation of African, Hispanic, Native and Asian Americans. ‘Rarely protagonists, ethnics merely provided local color, comic relief, or easily recognizable villains and dramatic foils’ (Lopez, 1991, p. 404). The effect of this marginalization produces the standard assessment. Hollywood’s ethnic representations were (and are) ‘damaging, insulting and negative’ (Lopez, 1991, p. 404).

Here I offer one version of this cinematic history, a racial and ethnic genealogy that cross-cuts gender, class, geography, and social science writings on race and ethnicity (McKee, 1993). This is a structural history. It emphasizes key historical moments and structural processes that shaped the representations of minority group members in American cinema during the twentieth century. These processes operated differently for each racial and ethnic group.

Following López (1991), I argue that it is possible to ‘pinpoint a golden or near-golden, moment when Hollywood, for complex conjunctural reasons, sees the light and becomes temporarily more sensitive to an ethnic or minority group’ (p. 406). These moments vary for each minority group (see below): after World War II for Jews and Latin Americans; after the civil rights movement of the 1960s for Hispanic, Asian, African, and Native Americans (López, 1991, p. 406). In these moments history is rewritten. Previous stereotypical representations are rejected and new understandings and stereotypes are constructed (López, 1991, p. 406).

With Lopez (1991, p. 405). I want to read these films, and their historical moments, as situated, modernist, naturalistic ethnographies (see Denzin, 1997, pp. 75–76). These cultural texts factually, authentically, realistically, objectively, and dramatically present the lived realities of race and ethnicity. These films perform race and ethnicity (Lee’s Pino talking to Mookie), and do so in ways that mask the filmmaker’s presence. This supports the belief that objective reality has been captured. These texts bring racial and ethnic differences into play through a focus on the talk of ordinary people and their personal experiences.

These are ethnographies of cultural difference, performance texts that carry the aura and authority of cinematic mimesis. They ‘realistically’ reinscribe familiar (and new) cultural stereotypes, for example young gang members embodying hip hop, rap culture (on the dystopic features of rap, see Gilroy, 1995, p. 80). These representations simultaneously contain and visually define the ethnic other. This is a mimesis that rests on the conditions of its own creation: white stereotypes of dark-skinned people.

These texts are cultural translations; they exoticize strange and different racial worlds, often revealing the ‘dirty secrets’ (Chow, 1995, p. 202) that operate in these exotic worlds. Borrowing from Chow (1995, p. 202), who borrows from Taussig, contemporary race and ethnic films constitute a ‘novel anthropology.’ The object of these texts is not the exotic world itself, but ‘the West itself mirrored in the eyes and handiwork of others’ (Chow, 1995, p. 202). As translations, these films bring positive and negative attention to the ethnic culture in question (Chow, 1995, p. 202). In so doing, they risk betraying the very world they valorize, for its meanings have now been filtered through the lens of the filmmaker as ethnographer.

Structural Commonalities

Hollywood’s treatment and representation of the ethnic other have been shaped by the following factors and processes: (1) nineteenth- and twentieth-century racist ideologies; (2) a pre-existing racist popular culture; (3) an early, racist silent cinema; (4) the advent of sound film (The Jazz Singer, 1927); (5) a widely understood racist performance vocabulary; (6) gender-specific cinematic racial stereotypes connected to (7) a series of film types and genres; (8) a segregated society that reproduced these cinematic stereotypes; (9) a pre-existing star system contained within a vertical integrated studio production system5 (Keller, 1994, p. 112) that used a racist film production code; (10) the production of literary and dramatic works with racial themes that could be made into movies, including those in the post-World War II realistic social consciousness, social problems tradition (1947–1962; Cook, 1981, p. 401; Keller, 1994, p. 127); (11) minority directors, actors, and actresses seeking cinematic work, expanding minority theatre audiences, and the appearance of theatres in racial ghettos (Bogle, 1994, p. 105); (12) America’s military history; (13) the civil rights and women’s movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

A brief discussion of each of these dimensions is required. I will then argue that each minority group has a different history with these structural processes. These are disjointed histories. They are marked by ruptures and interruptions, by the absence of continuity.

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century racist ideologies affirmed the white man’s burden in the arena of race relations; celebrated Anglo-Saxon nativism;6 emphasized the uncivilized nature of dark-skinned persons, and their threat to white society (including women); favored a ‘melting-pot’ assimilationist philosophy of racial difference (Musser, 1991, p. 39; Keller, 1994, p. 5); set immigration quotas; endorsed laws against miscegenation and integration; and sustaine...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Reading Race

- Part Two: Racial Allegories: The White Hood

- Part Three: Racial Allegories: The Black and Brown Hood

- Part Four: A New Racial Aesthetic

- Appendix: Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author