![]()

1

Creativity:

Meaning-Making and Representation

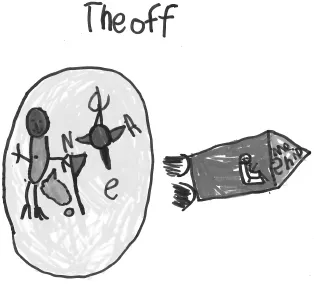

Figure 1.1 Lifting Off from Earth (boy, 6.6 i.e. 6 years, 6 months)

At the completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the important role of drawing in promoting creativity and meaning-making in young children,

- Understand graphic, narrative and embodied aspects of children’s meaning-making and representation, and

- Reflect on how the content of a child’s drawing is closely related to the form in which it is created.

Art and learning

The imagination is energetically deployed and reaches its peak in children’s early years of life, however, it gradually declines as children grow order. Yet as Egan (1999) urges, imagination is precisely what is needed to keep us intellectually flexible and creative in modern societies. Most notably, the arts ‘play to the imagination’ (Gadsden, 2008, p. 47). Gadsden elaborates that the arts:

allow individuals to place themselves in the skin of another; to experience others’ reality and culture; to sit in another space; to transport themselves across time, space, era in history, and context; and to see the world from a different vantage point. (p. 35)

Arts education and early childhood education in general have emphasized important principles that have increasingly found their way into more recent studies on multimodality and new literacies. Such studies have opened up debates about what ‘counts as a text and what constitutes reading and writing’ and have extended our notions of creativity (Hull & Nelson, 2005, p. 224). For decades, early childhood educators, artists and arts educators have recognized that the arts draw upon a variety of modalities, such as speech, image, sound, movement and gesture, to create multimodal forms of meaning. Such experiences are fundamental to the fluidity and flexibility of human thought and learning. Art provides young people with authentic meaning-making experiences that engage their minds, hearts and bodies.

This book focuses on how young children’s creativity is surfaced through the act of meaning-making within the medium of drawing. As will be illustrated through many examples of children’s works, drawing is an imaginative act which involves a range of creative forms of sign production and interpretation. Like all areas of learning, becoming competent in drawing generally requires exposure, participation and practice. It is when there is refined mastery of an art medium, combined with high levels of creativity and talent, that breakthroughs can be accomplished, such as in the case of Picasso. Picasso was an outstanding individual who showed exceptional artistic ability at an early age (Gardner, 1993a), and continued to develop his expertise throughout his life.

In a sense, every instance of representation through art is new and creative. Although drawing involves a ‘set of rules’, children never just mechanically apply rules when they make an artwork. Generally, each artwork is different and requires adaptation to the circumstances at hand. This is why composing through art is such an important and fundamental form of creativity.

Creativity

Several authors have written extensively on the topic of creativity. This literature will not be described in detail here, as the focus is on illustrating how creativity is demonstrated in young children’s art-making processes. However, some fundamental issues are featured at this time, and examples throughout this book will illustrate these, with a particular focus on meaning-making and representation through drawing.

Let us begin with a brief definition of creativity. Creativity is the process of generating ideas that are novel and bringing into existence a product that is appropriate and of high quality (Sternberg & Lubart, 1995). Everyone has at least some creative potential, but they differ widely in the extent to which they are able to realise that potential. In addition, as Gardner (1983, 1993a, b) pointed out, people tend to be creative or intelligent in some specific domains but not necessarily in others. For instance, we might be good at art, but not music; or be good at science, but not maths.

This is because creativity is a cognitive or mental trait and a personality trait as well. Some personal qualities include (Wright, 2003a): a valuing of creativity, originality, independence, risk-taking, the ability to redefine problems, energy, curiosity, attraction to complexity, artistry, open-mindedness, a desire to have some time alone, perceptiveness, concentration, humour, the ability to regress and the possession of childlike qualities. These personality traits are linked to thinking styles, which involve: visualization, imagination, experimentation, analogical/metaphorical thinking, logical thinking, predicting outcomes or consequences, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. In addition, intrinsic motivation and commitment are important personal qualities that are fundamental to the development of creativity.

Creative individuals were once widely seen as receiving divine inspiration for their ingenuity, and as needing nothing or anyone to excel. The stereotype is of a born genius whose innate talent does not require further honing or the support of others. Yet, in reality, the role of others is crucial throughout creative individuals’ development (Perkins, 1981). Creative activity grows out of the relationships between an individual, his/her work in a discipline and the ties between the individual and other people (or institutions) who judge the quality of his/her work (Csikszentmihalyi, 1988).

Hence, teachers, parents and the community influence children’s participation and development, and can support (or alternatively thwart) their creativity. Indeed, the decision to encourage or limit creativity is related to the attitudes of the significant people who shape children’s environments – whether they value creativity and are tolerant of the children’s ideas or products, even if these may challenge their own viewpoints or digress from conventional thinking and behaving.

Creativity is closely tied to personal connection, expression, imagination and ownership. It involves problem setting as well as problem solving. It comes out of explicit probing into meaningful issues, and constructing meaningful interpretations. Meaningful art-making reflects the ways of thinking of young artists – the makers who actively interact with the artwork. John Dewey (1934/1988) suggests that art offers multiple entry-points into the aesthetic experience, combining creation and appreciation. Indeed, children’s early representational drawings often emerge as a result of a dialogue between production and perception (Thompson, 1995; Thompson & Bales, 1991).

The imagination of the child can transform a blank piece of paper into something very real. Young children are careful planners during the creative process of drawing. They often decide in advance what content is to be included and where to locate it on the page. Frequently they review their work-in-progress and make additions or corrections. Golomb (2004, p. 191) emphasizes that composition in art is an ongoing process of revision, of ‘monitoring the performance, planning actions, inspecting the outcome, deciding on its merits and flaws’.

Although there are numerous ways in which creativity can evolve, some key processes are described in Table 1.1, along with an illustrative example of how these might apply to the medium of drawing. I am somewhat reluctant to introduce a range of technical terms, because these may seem to merely serve as a list or be viewed as being exhaustive rather than illustrative. Rather, the aim is to aid debate; by labelling some of the distinctive features of creativity in relation to drawing, allowing some security in the discussion. For a more extensive elaboration on some of these issues, readers may like to refer to some of my earlier works, particularly The Arts, Young Children and Learning (Wright, 2003a).

Artistic creation, through the medium of drawing, enables children to improvise. In the process, they develop a sense of arrangement and structure while transforming their graphic content on the blank page. This creative process is liberated through open-ended composing.

Table 1.1 Creative Processes, Descriptions and Examples

Composing through drawing

Bresler (2002, p. 172) described Child Art as ‘original, open-ended (in at least some aspects) compositions which are intended to reflect students’ interpretations and ideas’. While composing, children are comfortable with altering their artworks to suit their purpose. They feel at liberty to improvise structures as they dialogue with the materials, such as changing birds to butterflies, scribbling out a dead figure or turning grass into water. A number of things may stimulate a child to improvise in ways such as these, which may include:

- changing the identity of a character (e.g., deciding that a prototypic rock star in a drawing should be the artist himself)

- altering the plot content (e.g., modifying the structure of the plot by introducing a new theme, scene or event)

- modifying the genre of the narrative (e.g., shifting from factual to fictional)

- adjusting the time frame (e.g., shifting between the present, future or past)

- varying the place (e.g., turning a house into a hotel)

- confronting a challenging schema (e.g., leaving ‘Daddy’ out of a family scene because the artist does not know how to draw men’s clothes), or

- seeing another image in what has been drawn (e.g., thinking that a drawn dog looks more like a bear, and adding salient content to refine the image).

Most children seem to find composing through art an appealing process, perhaps because it is not strictly rule-bound. Children are at liberty to experiment and to represent ideas and actions in whatever form they choose. Hence, my intention is to feature not just the content of children’s artworks, but to also emphasize how the form of this content is meaningful. I want to highlight how children’s art making is an active, meaning-making experience. Like Kress (1997), I take the position that children’s visual narrative texts have structure, and that the structure that is given to these texts is done so through the interests of the text makers. It is a transformative process. The signs that children make are different from adult forms, but nonetheless, they are fully meaningful.

Art allows children to ‘say’ and ‘write’ what they think and feel, usually without adult intrusion. Through such open-ended experiences, children develop a repertoire of marks, images and ideas. They refine these through practice and skill and through exposure to the art of other children and adults. In the process, children experiment with ‘the language’ of the materials and develop a ‘grammar’ of communication. As mentioned above, they decide not only on the content to be depicted, but also the aesthetic form, or the manner in which content is presented. The artwork’s compositional component is a vital element of the child’s communication. It is the organizational force used to project ideas and to illustrate relativity and relationships. Composition not only makes the content accessible, it also heightens the young artist’s perceptions and stimulates his or her imaginative involvement.

When composing through drawing, children combine graphic, narrative and embodied signs. Dyson (1993) noted that at around the age of two, children often use drawing as a prop for storytelling, complemented with dramatic gesture and speech. These multimodal texts involve drawing, gesture and talk – they stem from visual, linguistic, aural and tactile modes to make meaning. Indeed, the marks that children make are often the ‘visual equivalent of dramatic play’ (Anning, 1999, p. 165).

Because of the play-oriented, compositional component of drawing, I believe art is essentially the literacy par excellence of the early years of child development (Wright, 2007b). As many have noted, infants and very young children generally draw prior to the acquisition of the skills of reading and writing written text (i.e., letters, words, phrases, sentences). Gunther Kress, in his book Before Writing (1997, p. 10), describes the social, cultural and cognitive implications of the ‘transition from the rich world of meanings made in countless ways, in countless forms, in the early years of children’s lives, to the much more unidimensional world of written language’.

Indeed, the act of representing thought and action while drawing actually strengthens children’s later understanding of literacy and numeracy. Unfortunately, however, many traditional systems of schooling suppress children’s free composing through drawing in favour of teaching children the more rule-bound, structured symbol systems of numeracy and literacy. This is because schools often perceive writing letters, words and numbers as a ‘higher status’ mode of representation (Anning & Ring, 2004). Yet, as Pahl and Rowsell (2005, p. 43) noted, many children are constrained by a literacy curriculum that only allows writing. They asserted that a multimodal approach ‘lets in more meaning’.

To focus too strongly, too soon, on a literacy curriculum distracts children from the ability to compose using pictorial signs, which in many ways are developmentally more meaningful to young children. When picturing and imagining within the ‘fluid’ boundaries of art, children are in control of what they want to say and how they want to say it, in a free-form way. The less rule-bound system of drawing offers children freedom of ‘voice’. When this co-exists with the learning of the more structured symbol systems, children engage in creative meaning-making in an assortment of ways.

Composing through art, like play, is a fundamental function of early cognitive, effective and social development. Through art, children actively construct understandings of themselves and their worlds, rather than simply becoming the passive recipients of knowledge. To suppress and replace artistic play with formal teaching not only denies the voice of children, but overlooks the significance of composing in the act of meaning construction.

Yet, Kress emphasized that, perhaps in the absence of strong theoretical descriptions and explanations of art, drawings and images of most kinds are thought of as being about expression, rather than about information or communication. Hence, art is not usually subjected to the same analysis for meaning, or seen as being as important a part of communication as language (Kress, 1997, p. 35). Kress adds that if the makers of the artworks are children, the question of ‘intentionality and design becomes contentious’ (Kress, 1997, p. 36).

The goal of this book is to overcome some of these misconceptions by provid...