- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Formative Assessment for Teaching and Learning

About this book

?A unique blend of scholarly research-based principles of effective formative assessment with practical suggestions for use in the classroom. The authors show how the essence of formative assessment is in teachers? responses to the substance students? understandings, with a focus on how teachers can use pedagogical strategies to move students forward toward important learning outcomes. I highly recommend the book for both researchers and practitioners. It is an engaging, in-depth, sophisticated treatment of formative assessment.?

- James H. McMillan, Virginia Commonwealth University

Formative Assessment (AFL) supplies the strategy to support effective teaching, and to make learning deep and sustained. This book shows how to develop your planning for learner-centred day-to-day teaching and learning situations through an understanding of formative teaching, learning and assessment.

Within each chapter, based on real teaching situations, the strategies of the ?formative assessment toolkit? are identified and analysed:

- James H. McMillan, Virginia Commonwealth University

Formative Assessment (AFL) supplies the strategy to support effective teaching, and to make learning deep and sustained. This book shows how to develop your planning for learner-centred day-to-day teaching and learning situations through an understanding of formative teaching, learning and assessment.

Within each chapter, based on real teaching situations, the strategies of the ?formative assessment toolkit? are identified and analysed:

- guided group teaching

- differentiation

- observation & evidence elicitation

- analysis & feedback

- co-construction

- reflective planning

- self-regulation

- dialogue & dialogic strategies.

The principles set out in this book can be applied to any age or stage in education, but will be particularly useful to current practising teachers, students following international and national teacher training courses; CPD or in-service work; and MEd and MA post-graduate assessment/teaching and learning modules.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What is Formative Assessment?

In this chapter we look at different ideas about formative assessment and consider teacher beliefs about formative assessment.

Sharing definitions

We carried out a research survey in UK primary schools in 2008 – five years after assessment for learning had been formally introduced into the national teaching and learning agenda through the Primary strategy: ‘Excellence and Enjoyment’ (DfES 2003) – to investigate how standardised the definition of formative assessment was across schools. The results were surprising, with a wide range of definitions expressed by teachers. It is essential, therefore, that formative assessment has a clear definition so that its practice can be understood and improved by teachers. The literature in the research field offers several interpretations and definitions. For example, Coffey et al. (2011) suggest that ‘formative assessment should be understood and presented as nothing other than genuine engagement with ideas, which includes being responsive to them and using them to inform next moves’ (p. 1129), while US researcher James Popham’s definition states clearly that ‘formative assessment is not a test but a process that produces not so much a score but a qualitative insight into student understanding’ (Popham 2008, p. 6). The process and outcomes of formative assessment are the focus for Bennett whose definition links the teaching, learning and assessment activity: ‘formative assessment involves a combination of task and instrument and process’ (2011, p. 7)

According to socio-constructivist learning theory, individuals assimilate knowledge and concepts after restructuring and reorganising it through negotiation with their surroundings, including fellow learners (Hager & Hodkinson 2009; Rogoff 1990). All children do not learn all that is taught and teachers cannot know what and how well concepts are understood without using some process to establish pupil understanding. Since each pupil has his/her own unique socially constructed context, ideas, concepts and meanings are not fixed nor standardised across a group or class of pupils. Therefore the individual outcomes of learning situations will be diverse. The word ‘assessment’ derives from the Latin word ‘assidere’ meaning ‘to sit beside’ – this can be taken to imply a close proximity or association between the assessor and the learner in the assessment process (Good 2011).

Criticism of an assessment process which had traditionally been designed to grade and certificate led to the emergence of formative assessment, a concept designed to support pupils’ learning processes. ‘Beginning in the 1960s researchers and authors from a range of disciplinary backgrounds weighed in against the proliferation of classification practices stemming from the American psychometric current, thus opening the way to prioritising assessments that measured students’ learning’ (Morrissette 2011, p. 249). These researchers included, in sociology, Becker (1963), Bourdieu and Passeron (1970), Perrenoud (1998, 2004), in anthropology, Rist (1977), in palaeontology, Gould (1981), in philosophy, Foucault (1975), and in evaluation Crooks (1988), Mehan (1971), and Popham (2008) have drawn attention to issues such as the consequences of testing practices on narrowing classroom pedagogy and culture.

For example the secondary adaptations (plagiarism, cramming) that pupils develop in a context which continually threatens their integrity and self-esteem; the cultural biases of the tests used to assess their learning; the ‘instrumental illusion’ that is, the ingrained belief that it is possible to exclude all the interpretive processes which are necessarily involved in these practices; and finally the power ascribed to evaluation practices that, on the one hand, contribute to a form of control and standardisation and on the other, perpetuate social disparities. (Morrissette 2011, p. 249)

From these beginnings, there has been an increasing interest in the formative principles and functions of assessment serving to support children’s learning rather than to grade pupil outcomes.

Research on formative assessment practices has covered a range of disparate approaches: a focus on the choice of tasks and the context in which they are carried out (Wiggins 1998); formative assessment as a means of modelling, designing and supporting professional development (Ash & Levitt 2003; Boyle et al. 2005); assessment criteria (Torrance & Pryor 2001); the feedback provided to pupils (Hattie & Timperley 2007); and pupils’ views about assessment (Cowie 2005).

Linda Allal (1988) has produced a typology of remediation post-assessment of a learning objective for a concept as follows:

• Retroactive adjustment: which takes place after a shorter or longer learning sequence, on the basis of micro-summative evaluation

• Interactive adjustment: which takes place through the learning process

• Proactive adjustment: which takes place when the pupil is set an activity or enters a teaching situation.

These three methods may be combined and none of them are to be associated with a stereotyped procedure. Retroactive adjustment may take the form of a criterion-referenced test followed by remediation. Retroactive adjustment may mean going over much earlier material and temporarily refraining from ‘pushing’ the child to learn things that may cause him/her problems. It may also entail adjusting other aspects of the teaching situation or even the child’s progress through the school.

Enlarged understandings of formative assessment

How assessment links to and is an ongoing inherent aspect of teaching and learning is a perennial issue. In this debate, the definition and role of assessment are crucial. A reductionist definition of assessment with its aim defined as an increase in learner ‘performance’ measured as test data is too narrow a concept to guide teaching. In England, despite the desire and the recommendation of the Task Group on Assessment and Testing (DES 1988) the reduction of assessment to being viewed as synonymous with ‘testing’ and a one-dimensional view of ‘performance’ is exactly the situation that has become reality in the 25 years since TGAT reported.

The TGAT proposed that teachers should assess only that which is observable. Teaching decisions, especially the decision to move on to the next part of the curriculum, should always be based on an assessment, no matter how informal, of the learner’s response to the current activity. It is that assessment of current achievement which is the basic building block of any assessment system in the context of a National Curriculum. Assessment in the context of the National Curriculum was not designed to predict how a learner will do in later life, by trying in some way to measure ability or effort. National Curriculum Assessment was intended as a means of demonstrating how children were progressing through the level structure of the entitlement curriculum. However, it has ceased to be criterion-referenced (definition) and now serves as a means of norm-referencing children and schools.

Formative assessment was legitimised and became part of the education policy makers’ and teaching fraternity’s lexicon through the seminal Task Group on Assessment and Testing report (DES 1988) which developed the assessment system for the National Curriculum encompassed by the 1988 Education Reform Act (DES 1988). However, with the commencement of paper and pencil testing of the National Curriculum (the ‘sats’) in 1991, soon the only form of ‘assessment’ which mattered was summative and this was embodied in the end of key stage tests. These quickly became a ‘high stakes’ priority for schools who felt pressured by both Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education) and the government who used the test results as the principal (often, it appeared to teachers, the sole) measure of national standards and each school’s success or failure. This was a very one-dimensional ‘standards agenda’ as its sole focus was on a school’s test scores based on the sub-domains of English and mathematics measured against arbitrarily set national percentage targets.

Officially, summative Teacher Assessment (TA) has ‘parity’ (Dearing 1994) with the test outcomes – but the school performance ‘league’ tables use only the test data. The (non-formative) purpose of TA was designed to be the holistic award of a teacher judgement ‘level’ for each child at the end of the school year. This attainment judgement was based on the child’s progression through an 8-level scale, the judgements to be made as a ‘best fit’ of the child’s ‘performance’ against a prose paragraph describing performance at each level (Boyle 2008; Hall & Harding 2002). This task required standardisation of definitions of quality (at school, regional and national levels) for any judgements to be transferable as reliable and valid. ‘Unless teachers come to this understanding and learn how to abstract the qualities that run across cases with different surface features but which are judged equivalent they can hardly be said to appreciate the concept of quality’ (Sadler 1989, p. 128). This necessitated dialogue, communication and collaboration by teachers with their colleagues within and essentially across schools and as this strategy was financially unsupported by central government it was soon ‘dismissed’ by teachers. Their reasons included ‘workload’, difficulties of communication, administration and logistics of meetings to share understandings and meanings of children’s work. Significantly, the ‘sats’ scores were conveniently received by schools before the date for national returns of TA, enabling schools to avoid disagreement between test and TA and reduce workload by returning as near a match as possible across the two scores (Reeves et al., 2001). The test and TA reported levels were in accord so there appeared to be no need to further investigate a school’s performance. The TA process has become even further complicated with the introduction of Assessing Pupil Performance (APP), a government strategy which stresses the making of judgements at sub-levels (2a, 2b, 2c) and then at sub-sub-levels, e.g. high 2c, secure 2c, low 2c.

Both summative and formative approaches to assessment are important. Summative assessments are ‘an efficient way to identify students’ skills at key transition points such as entry into the world of work or for further education’ (OECD 2005, p. 6). Tests and examinations are the traditional ways of measuring student progress and have become integral to the accountability of schools and the education system in many countries. However, internationally assessment has become almost universally equated with high stakes scoring and testing ( Hall et al. 2004; Shepard 2000, 2005; Twing et al. 2010) and teaching has consequently been reduced to servicing that metric (Guinier 2003).

Much of the common emphasis on formative assessment has been that it occurs within learning activities rather than subsequent to them. It provides information for the teacher to use to make judgements during a lesson or day-to-day in the planning of matched materials for students in lessons (Ramaprasad 1983; Shepard 2000). Formative assessments are often used synonymously with benchmark or interim assessments and in reference to student performance on test items (Bennett 2011; Popham 2006). Popham defines formative assessment as ‘not a test but a process’ that, as Shepard adds, can ‘inform instructional decision-making’ (Shepard 2000).

What is an acceptable definition of formative assessment?

We used a quotation from Perrenoud in the Introduction to this book: ‘Any assessment that helps a pupil to learn and develop is formative’ (1991, p. 80). However, the statement needs development. The core of formative assessment lies not in what teachers do but in what they see. The teacher has to have awareness and understanding of the pupils’ understandings and progress. ‘To appreciate the quality of a teacher’s awareness, it is essential to consider disciplinary substance: what is happening in the class and of that what does the teacher notice and consider? (Coffey et al. 2011, p. 1128). Do the teachers neglect the disciplinary substance of student thinking? Do they presume only traditional targets of (subject) as the body of information (to be taught and then assessed), selected in advance? Do they treat assessment as strategies and techniques for teachers? It is imperative that teachers consider student thinking not only with respect to its alignment with the ‘linear curriculum’ but also with respect to the nature of the students’ participation. Students’ acceptance that 8 squared equals 64 could be seen as alignment with the taught curriculum. However, if students accept that calculation on the teacher’s authority, rather than because they experience the problem, design the calculation and see the result supported by evidence and reasoning they become passive recipients of the transmission of knowledge. ‘Therefore it is essential that formative assessment – and accounts of it in the literature – consider more than the “gap” between pupil thinking and the correct concepts’ (Coffey et al. 2011, p. 1129).

It is attention to pupil thinking that will cause the teacher to abandon his/her original plan for a lesson. Formative assessment will create ‘learning objectives’ that a teacher will not have had in his/her conceptual planning at the outset – and at two levels. The first level is one of conceptualisation – how the child understands the concept – while the other objective is at the level of how the child approaches the theme/concept. The teacher should be constantly working to move students into engaging with the theme/concept as researchers and away from the ‘classroom game’ (Lemke 1990) of telling the teacher what they think s/he wants to hear.

In conceptualising assessment as ‘learner behavioural analysis’, the teacher is formatively assessing student thinking by paying close attention to the demonstrations through behaviours and outcomes of that thinking. S/he wants to understand what the students are thinking and why – as surely would any participant in any meaningful discussion. Formative assessment should be understood and presented as nothing other than genuine engagement with ideas, which includes being responsive to them and using them to inform next moves (Coffey et al. 2011, p. 1129). For example, the teacher is exploring ideas about rainfall with a group of primary children. She originally had set up the dialogue linked to weather in a discussion of words and phrases such as ‘wet’, ‘cloudy’ and ‘splashing in the puddles’. One child extended the discussion into the related area of her own bath time and used vocabulary related to that experience such as ‘the water washes over me’. In this context the formative teacher re-shaped her original idea and teaching concept to the perspective and location of the learners, i.e. the child whose thinking had moved on to ‘water’ produced a ‘water’ poem.

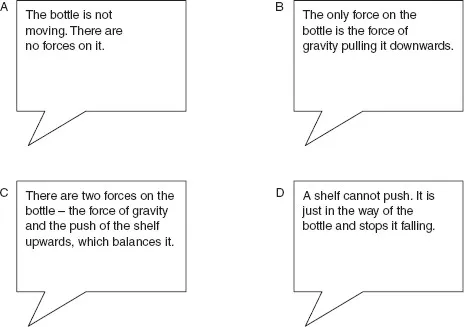

A teacher’s model of formative assessment in practice should be in close proximity physically and temporally with what the teacher planned that children would learn: the practice of assessing the quality of their own ideas for their fit with their learning objectives. Effective assessment is part of the learning process for children. It is important that they understand, for example, in studying ‘forces’, what the specific kinds of forces are, but through their own experimentation, for example using concept cartoons such as ‘Bottle on the shelf’ which open dialogue about the kinds of forces and their actions to move a bottle placed on a shelf (see Figure 1.1). In that case, children are learning to assess ideas as ‘nascent scientists’ rather than as compliant students. Understanding these discipline-based assessment criteria is part of what educators should help children learn. As children begin to engage in disciplinary assessment, they are learning a fundamental aspect (of their subject) (Coffey et al. 2011, p.1129).

Figure 1.1 Bottle on the shelf evidencing the force of gravity

Teachers do not need strategies (traffic lights, two stars and a wish) to become aware of and more responsive to children’s thinking. This begins with a shift of attention, with a shift of how the teacher frames, and how s/he asks the pupil to frame, what is taking place in the classroom. This orientation towards responsiveness to pupils’ ideas and practices resonates with work in teacher education (particularly in mathematics, see Ball et al. 2008; Kazemi et al. 2009) that has pushed for more practice-based accounts of effective preparation. This resonates with learning to teach ‘in response to what students do’ (Kazemi et al. 2009) and more attention to ‘demands of opening up to learners’ ideas and practices connected to specific subject matter’ (Ball & Forzani 2011, p. 46). By this reasoning, much depends on how teachers frame (plan) what they are doing – and the primary emphasis on strategies (gimmicks) in teacher training may be a part of the problem. Assignments that direct teachers and teachers in training to what they are doing may inhibit their focus on what pupils are thinking. With Coffey et al., we suggest the need for a shift away from the strategies that teachers use as the sole focus of their attention in class, and from that shift a re-framing of what assessment activities entail. We propose that it is essential for teachers to frame what is taking place in class as centred on pupils’ ideas and reasoning, nascent in the subject area or domain. Formative assessment then becomes about engaging with and responding to the substance of those ideas and reasoning, assessing with discipline-relevant criteria, and, from ideas, recognising possibilities along the disciplinary horizon. Formative assessment moves out of strategies and into classroom interaction with roots in disciplinary activit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Education at SAGE

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 What is Formative Assessment?

- 2 The Guided Group Strategy

- 3 Differentiation

- 4 Observation and Evidence Elicitation

- 5 Analysis and Feedback

- 6 Co-construction: The Active Involvement of Children in Shaping Learning

- 7 Reflective Practice

- 8 Self-regulated Learner: Learner Autonomy

- 9 Dialogue and Dialogic Teaching

- 10 Ways Forward

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Formative Assessment for Teaching and Learning by Bill Boyle,Marie Charles,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Evaluation & Assessment in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.