- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Essential Guide to Using the Web for Research

About this book

Nigel Ford shows how using the web poses opportunities and challenges that impact on student research at every level, and he explains the skills needed to navigate the web and use it effectively to produce high quality work.

Ford connects online skills to the research process. He helps readers to understand research questions and how to answer them by constructing arguments and presenting evidence in ways that will enhance their impact and credibility.

The book includes clear and helpful coverage of beginner and advanced search tools and techniques, as well as the processes of:

@!critically evaluating online information

@!creating and presenting evidence-based arguments

@!organizing, storing and sharing information

@!referencing, copyright and plagiarism.

As well as providing all the basic techniques students need to find high quality information on the web, this book will help readers use this information effectively in their own research.

Nigel Ford is Professor in the University of Sheffield?s Information School.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

Introduction

Why read this book?

- The first skill you need is to know what is required of you – what your lecturers expect to see in a good piece of work at university level, and what differentiates it from a less good piece of work. (Chapter 2)

- If an essay question asks you to describe, analyse or evaluate a topic, you need to know exactly what these words mean and how they differ. It’s no good producing a first-class description when your lecturer wants an analysis or an evaluation. In other words, you need to be able to accurately decode and interpret the specific instructions you are given for each piece of coursework. (Chapter 3)

- As your course progresses, you will increasingly be expected to develop and display skills in finding information for yourself – rather than relying on reading lists given to you by your lecturers. You’ll be expected to know what peer-reviewed information is, and to be able to find it. This is not just a case of using Google or your university library catalogue. There is a range of sophisticated tools available to you specifically designed to find high-quality information. This book will introduce these to you and show you how to use them to best effect. (Chapters 4–8)

- You will then be expected to use it to build an evidence-based response to your essay or research question – the hallmark of a high-quality piece of work. This will entail analysing, synthesising, evaluating and selecting information. You need to be able to present your argument in an academically convincing way – to convince the person marking your work that the evidence that you are putting forward to support your arguments is valid, reliable and unbiased. You must know exactly what these terms mean, and how you can make sure that your work meets these essential quality criteria. This book will clearly explain these terms and will take you through these processes step by step. (Chapter 9)

- It will be essential to show that your work is your own. You must avoid plagiarism at all costs. Plagiarism is passing off the ideas of other people as your own and it can be done unintentionally as well as deliberately. It is a serious offence, and there are many cases of students being given severe penalties when found guilty of it. However, to produce high-quality work, you do need to draw on and use the ideas of others – writers and experts in the field. The key skill enabling you to build on other people’s work whilst at the same time avoiding plagiarism is knowing how to correctly attribute your sources. This book takes you through this process, and gives many examples of how to correctly cite different types of source. (Chapter 10)

- Showing that you have made use of information that is not only suitably authoritative but also the latest available will greatly benefit your work. You need to keep up to date with what is being published on the topics you are working on in your courses. However, you do not need to constantly keep checking to see if anything new has been published. This would be a waste of your time, especially if nothing new has appeared since last time you checked. This book explains a number of techniques that will enable you to receive automatic updates straight to your computer whenever something new is published on your topics. (Chapter 11)

- You can also save time if you organise your information effectively. Your personal store of information sources will become increasingly large as you work your way through your university courses. Storing them in your own personalised online library, searchable by author, title, keyword and your own tags, can save a lot of time and effort – for example, if you are trying to link ideas and quotations in an essay or report back to where you originally found them. Reference management tools are designed to help you manage your information sources in this way. They can also enable you automatically to create and update bibliographies in your work – and to change the citation style at the click of a button. You can also share your references – and your comments and tags – with friends and fellow students over the web. (Chapter 12)

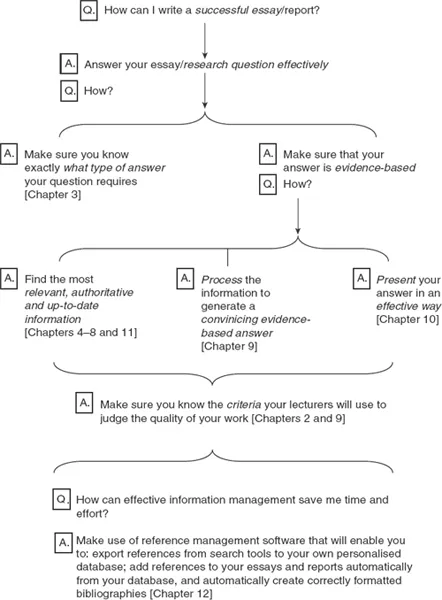

The book’s underlying rationale

Search tools covered in this book

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the author

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Learning & critical thinking: the essentials

- 3. Clarifying what is required of you

- 4. Finding high-quality information

- 5. How to do a literature review

- 6. Information sources and search tools

- 7. Mapping search approaches & techniques to information needs

- 8. Scholarly search tools in detail

- 9. Transforming information into evidence-based arguments

- 10. Presenting your evidence effectively

- 11. Keeping up to date

- 12. Organising & sharing your information

- Postscript

- Appendix: your learning style

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app