- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Qualitative Research and Ethnomethodology

About this book

Understanding Qualitative Research and Ethnomethodology provides a discussion of qualitative research methods from an ethnomethodological perspective. Detailed yet concise, Paul ten Have?s text explores the complex relation between the more traditional methods of qualitative social research and the discipline of ethnomethodology. It draws on examples from both ethnomethodological studies and the wider field of qualitative research to discuss critically an array of methods for qualitative data collection and analysis.

With a student-friendly structure, this engaging book will be an invaluable resource for both students and researchers across the social sciences.

With a student-friendly structure, this engaging book will be an invaluable resource for both students and researchers across the social sciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Qualitative Research and Ethnomethodology by Paul ten Have in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Qualitative Methods in Social Research

The purpose of this book is to stimulate reflection on ways of doing qualitative social research by asking the general question, ‘How is qualitative social research possible?’ In this chapter, I offer some basic considerations about this topic in order to prepare for the discussions in the later chapters. I will use the word methods in a rather loose sense, as ways of doing research, both on the level of principles, general research strategies or policies, and on the level of actual research practices. Consideration of methods is relevant ‘from beginning to end’, from the first intentions and ideas until the final publications and presentations. This book is about methods, but it does not offer ‘a methodology’. It does not present a ‘correct way of doing research’, summarized in algorithms that, when followed faithfully, lead in a kind of quasi-automatic way to ‘good results’. In my opinion, the only sensible way in with methods can be discussed, at least in qualitative research, is by treating them as heuristic possibilities that need to be adapted to local circumstances and project-specific purposes, if they are to be of any use.

The meaning of social research may seem obvious, but a few words are in order, to frame the ways in which it will be used in later discussions. I will use ‘research’ to refer to all kinds of knowledge production that involve the inspection of empirical evidence. ‘Social research’, then, collects research endeavours that focus on ‘the social’, that is, phenomena that are related to people living together, whether these are conceptualized as structures, processes, perspectives, procedures, experiences or whatever. Social research can be a part of many different kinds of activity, but for now I will limit my considerations to research activities within the realm of ‘social science’, broadly conceived. Practitioners or others involved in research without a strictly scientific purpose, like evaluation research, advocacy research or market research, will hopefully find my reflections useful, but I will deal with matters at hand mainly from a social science perspective.

What, then, is science, even if only social science? I think that science cannot be usefully differentiated from other inquisitive activities by claims to an exclusive relationship to some specific principles or methods. It is, rather, distinguishable as a particular way of investigative life by its general purpose and approach. Its aim, to paraphrase some notions developed by Charles Ragin (1994), is to contribute to an ongoing dialogue of ideas and evidence concerning some ‘reality’, in this book limited to a social reality of people living together. And its approach, I would suggest, is to take the time needed to make one’s contribution a valid one. As Dick Pels (2001) has suggested, the demarcation of ‘science’ from other kinds of inquiry should not be seen, and treated, as a sharp ‘break’, but rather as a series of less sharp barriers (or barricades!) which allow practitioners of scientific inquiry to ‘take their time’, to think, to read and re-read, to collect data, to (re-)consider the evidence, etc. In other words, science requires some protection from the hectic nature and the haste of practical lives and interests, of politics, media attention and the market, if it is to be able to work on its mission.

Ideas and evidence in social research

In his Constructing social research: the unity and diversity of method, Charles Ragin (1994) has tried to catch some of the essential general properties of social research in what he calls ‘a simple model of social research’. As he sees it:

Social research, in simplest terms, involves a dialogue between ideas and evidence. Ideas help social researchers make sense of evidence, and researchers use evidence to extend, revise, and test ideas. The end result of this dialogue is a representation of social life - evidence that has been shaped and reshaped by ideas, presented along with the thinking that guided the construction of the representation. (Ragin, 1994: 55)

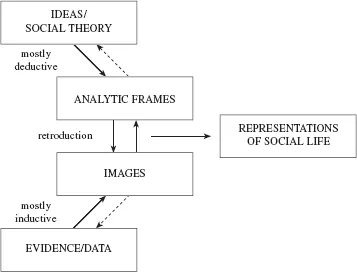

Because the ‘distance’ between abstract and general ‘ideas’ and concrete and specific ‘evidence’ tends to be a large one, his model specifies some mediating structures, called ‘analytic frames’ and ‘images’, between the two. Analytic Frames are deduced from general ideas and specified for the topic of the research, while Images are inductively constructed from the evidence, in the terms provided by an analytic framework. The researcher’s core job is to construct a ‘Representation of Social Life’, combining analytic frames and images in a ‘double fitting’ process called ‘retroduction’ (i.e. a combination of deduction and induction).

In Figure 1.1, I ‘quote’ Ragin’s visualization of this model.

In this schema, ideas are placed in the top left corner and evidence at the bottom. This suggests that they represent the starting points for the analysis, the ‘givens’, in a way. A bit to the right, we see the analytic frames below the ideas, and the images above the evidence. Arrows indicate the processes that connect these elements: from the ideas to the analytic frames a strong deduction and a weak induction in the opposite direction; similarly, there is a strong induction arrow from the evidence to the Images, and a weak deduction in the opposite direction. The general ‘givens’, the abstract ideas and the concrete research materials, are worked on: specified to fit the research topic. Between the analytic frames and the images, we see two arrows, one upwards and one downwards. These represent the core activity, the ‘dialogue’ mentioned above. Finally, more to the right, there is an arrow from the double arrows to a box labelled ‘Representations of Social Life’. The results of the dialogue are to be communicated. What the figure as a whole depicts is a set of dynamic relationships between the elements – arranged from the most abstract at the top, to the most concrete at the bottom; and the earlier to the left, and the later to the right – in the research process.

Figure 1.1 A simple model of social research

One can say that the various traditions in social research differ from each other in the kinds and contents of their leading ideas, in the character of the evidence used, and in the manner in which the dialogue of ideas and evidence takes form in their practices and public presentations. One major contrast would be that some stress the ‘downward’, deductive kind of reasoning, while others prefer to argue ‘upwards’, inductively. Ragin stresses, however, as visualized by his double arrows, that in actual practice there is always a two-way reasoning, a dialogue between the various levels. The model is, of course, a simplification in many ways, but it offers a useful device to organize some aspects of my discussions in this book.

Types of social research

Earlier in his book, Ragin (1994: 33 and passim) distinguished three major types of social research, based on their general goals and specific research strategies: qualitative, comparative and quantitative research. Qualitative research is especially used to study what he calls ‘commonalities’, i.e. common properties, within a relatively small number of cases of which many aspects are taken into account. ‘Cases are examined intensively with techniques designed to facilitate the clarification of theoretical concepts and empirical categories.’ In Ragin’s version of comparative research (cf. also Ragin, 1987), the focus is on diversity and ‘a moderate number of cases is studied in a comprehensive manner, though in not as much detail as in most qualitative research’. It ‘most often focuses on configurations of similarities and differences across a limited number of cases’. Quantitative research, finally, investigates the covariation within large data-sets, that is, a relatively small number of features is studied across a large number of cases. So the focus is on ‘variables and relationships among variables in an effort to identify general patterns of covariation’.

As a first approximation, these characterizations seem to be very useful. On the qualitative side, many would like to add some further features, preferences and assumptions. For instance, rather than trying to explore ‘common’ features, many qualitative researchers report their findings in terms of a typology or even a contrast. Furthermore, most qualitative research tends to be based on an ‘interpretative’ approach, in the sense that the meanings of events, actions and expressions is not taken as ‘given’ or ‘self-evident’, but as requiring some kind of contextual interpretation. What kind of ‘contexts’ have to be invoked may, of course, be a matter of preference and debate. One may look, for instance, at the surrounding text, the social setting and/or the encompassing ‘culture’. Furthermore, choosing a qualitative approach suggests that the phenomena of interest are not at the moment ‘countable’, whether for practical and/or for theoretical reasons. And there are large differences among qualitative researchers in other respects. Some would use a ‘language of variables’, as quantitative researchers do, which would be an anathema to others, who prefer a less ‘scientistic’ and more ‘humanistic’ or ‘holistic’ approach and a language that fits that style. Most qualitative researchers prefer a relatively ‘open’ or ‘exploratory’ research strategy, starting with some ‘sensitizing concepts’ (Blumer, 1969) which may become more precise as the research progresses. For some this represents what they would call the preparatory phase of research, for which a qualitative approach is best fitted, later to be followed by a decisive test in a quantitative project. Others would resist such a limited job description for qualitative research, saying that exploration and testing can go on, hand in hand, within a single qualitative project, or across projects.

Qualitative versus quantitative

An obvious strategy to elaborate the core characteristics of qualitative research, then, is to contrast it with quantitative research, although this may hide internal differences. The defining feature of quantitative research, that its results can be summarized in numbers most often arranged in tables, is absent, or at least not dominant, in qualitative research. In other words, while the results of quantitative research can be presented in numerical form, those of qualitative research require verbal expressions, and often quite extensive ones at that. In the typical case, the primary material of quantitative research is also verbal, but the basic features of the design are oriented to quantification, or one might say ‘numerification’. These include systematic sampling, standardization of data collection, and statistical data management techniques. The essential movement of the research is the reduction of large amounts of distributed information to numerical summaries, means, percentages, correlation coefficients, etc. As Charles Ragin (1994: 92) remarks: ‘Most quantitative data techniques are data condensers’ and ‘qualitative methods, by contrast, are best understood as data enhancers’. The crucial feature of qualitative research, then, is to ‘work up’ one’s research materials, to search for hidden meanings, non-obvious features, multiple interpretations, implied connotations, unheard voices. While quantitative research is focused on summary characterizations and statistical explanations, qualitative research offers complex descriptions and tries to explicate webs of meaning.

Styles of qualitative social research

While quantitative methods seem to be part of one unitary model of doing research, including standard criteria of adequacy, qualitative research offers a wide variety of methods, aims, approaches – in short, styles.

Interview studies

Without any doubt, the most popular style of doing qualitative social research, is to interview a number of individuals in a way that is less restrictive and standardized than the one used for quantitative research. The researcher may prepare a number of topics or even questions that are to be brought into the conversation in a more or less systematic or quasi-natural way. The respondent may be asked rather specific questions or may just be requested to talk at length on one or more themes. The encounter may be one-to-one or the researcher may organize a group discussion. There is, then, within the interview style an enormous range of variation. The crucial property, however, is that the researcher arranges sessions with the research subjects in which the latter talk about their ideas and experiences at the initiative of and for the benefit of the researcher. In that sense, the data produced in interviews have an ‘experimental’ quality; without the research project, they would not exist. Doing interviews has a number of obvious practical advantages. The researcher is able to collect a large amount of on-target information with a minimal investment in terms of time and social effort. One does not have to wait until a phenomenon of interest emerges naturally; one can work to have it created on the spot, so to speak. Doing an interview study is for many if not most qualitative researchers the obvious way of designing their projects. In Chapter 4 on interviewing, I will have occasion to discuss some possibly less popularly considered features of interview research, together with some less obvious possibilities.

As a classic example of an interview study, I refer to Passage through crisis: polio victims and their families, by Fred Davis, first published in 1963, and reissued with a new introduction in 1991. It is mostly based on a series of interviews with the parents of children passing through the trajectory of acute paralytic poliomyelitis and its aftermath. This study, and a few others, will be discussed at some length in Chapter 4.

Using documents

A rather different style of qualitative research involves the scrutiny of documents of various kinds. One can study ‘natural’ documents that are produced as part of an established social practice, such as bureaucratic records, newspaper reports, cartoons, musical scores, family pictures, works of art, home videos, email messages, etc. I use the term ‘document’ to refer to any preservable record of text, image, sound, or a combination of these. I will focus my discussion, in Chapter 5, on natural documents, although a researcher can, of course, also produce his or her own records, or have these produced by the research subjects for the purpose of his or her project. Using natural documents will involve the researcher in some kind of consideration of the processes that have produced those documents, practices of documentation, which I will also take up in that chapter.

I will mention here just one classical study to exemplify document-based research. It was done by Norbert Elias, published in 1939 in German as Über den Prozess der Zivilisation, and in English in 1978 as The civilising process. The core piece in the first volume of this masterly work on the history of Western civilization is based on a comparative study of various manner books, as well as subsequent editions of some of these, published in Germany, France, England and Italy, from the 13th through to the 19th centuries. The changes which can be observed in these texts are taken as indications of changes in the actual behaviour of the upper and middle classes at which these books were aimed (more on this in Chapter 5).

Ethnography

A minority of qualitative researchers are committed to the close observation of the actual, ‘natural’ situations in which people live their lives, trying to minimize the impact of their presence on their subjects’ actions. This style is known as ethnography. It used to be the stock-in-trade style of social and cultural anthropology. An anthropologist would live for a year with his or her tribe in order to describe crucial features of tribal life through a yearly cycle. This would involve a variety of data gathering techniques, including first of all learning the language, and then doing natural observations, asking for explanations, gathering kinship information, etc. Later, the label ‘ethnography’ came to be used to indicate any kind of r...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Qualitative Methods in Social Research

- 2 Ethnomethodology’s Perspective

- 3 Ethnomethodology’s Methods

- 4 Interviews

- 5 Natural Documents

- 6 Ethnography and Field Methods

- 7 Qualitative Analysis

- 8 Doing Ethnomethodological Studies

- 9 Reflections

- Appendix: Transcription Conventions

- References

- Index