- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

?Smith?s research interests in inclusive and gifted education are reflected in her publications and this book is no exception. This is essentially a user-friendly practitioner?s text, aimed at primary school educators...I would recommend this as a useful addition to the practising teacher?s repertoire of resource texts? Susen Smith, former primary school teacher

?The suggestions here, many of them photocopiable, are clearly tried and tested. All primary teachers will find them helpful? - Michael Duffy, The Times Educational Supplement

`A very useful aid to any staff room bookshelf. Easy to read, use and understand- National Association of Gifted Children Newsletter

`A must read for all teachers. This book not only sets out very clearly the needs of Able Gifted and Talented pupils, but also helps teachers reappraise their classroom practice and the role of the learner? - Johanna M Raffan, Director of NACE, National Association for Able Children

How can we provide challenges for the gifted and talented primary school pupil in an inclusive classroom setting?

Using tried and tested examples, this book shows the busy teacher how to challenge able children in their mixed-ability class - where time and resources are usually limited.

The practical tasks will show you how carefully designed activities can cater for a range of abilities. The book has sections on:

- creating a working environment that helps more able pupils to thrive;

- varying the way you ask pupils questions;

- thinking about multiple intelligences and ways to develop them;

- developing different levels of challenge in classroom activities;

- allowing pupils some choice in the activities they do;

- advice on how to run whole-class research projects.

A glossary of key terms and a range of photocopiable material are included.

Class teachers, GATCOs, Teaching Assistants, Learning Support Teachers, trainee teachers and LEA advisers looking for practical teaching ideas to challenge gifted children will find this book ideal for use in their settings.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Gifted Children in the Primary Classroom

In this chapter we will:

- Help you think about how your own beliefs about what giftedness is can influence pupil performance.

- Offer a circular model to consider giftedness in the primary classroom.

What teachers and pupils believe about gifts and talents

- can account for differences in achievement between pupils and by individual pupils over time;

- make a difference to the amount of effort a learner might put into an activity;

- can help to explain depressive reactions by pupils (yes, even in the primary school), to bad experiences in learning;

- and can be used to judge and label both ourselves and others.

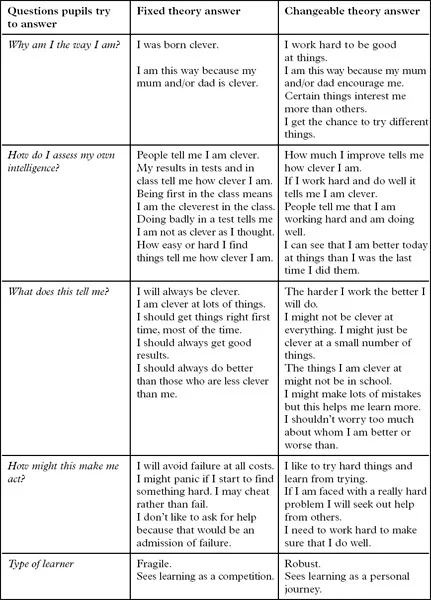

- Intelligence is fixed.

- Intelligence is changeable.

What does believing that intelligence is fixed mean for pupils?

Questions to consider

- Can I recognise any pupils who might have a fixed view of intelligence?

- To what extent do I have a fixed view of intelligence of my own learning?

What does believing that intelligence is changeable mean for pupils?

Questions to consider

- Can I recognise any pupils who might believe that intelligence is changeable?

- To what extent do I believe that my own intelligence is changeable?

What does believing that intelligence is fixed mean for teachers?

What am I good at?

- In school I am good at______________________________________

________________________________________________________ - Outside school I am good at_________________________________

________________________________________________________ - I am good at these things because_____________________________

________________________________________________________ - In school I am not so good at__________________________________

________________________________________________________ - Outside school I am not so good at_____________________________

________________________________________________________ - I am not good at these things because__________________________

________________________________________________________ - Do you think you could become good at these things? If yes, how?______

________________________________________________________ - Is there anything that you think you will never be able to do well? If yes, why is this?

________________________________________________________ - What is more important – to be the best in the class or do better than you did last week?____________________________________________

________________________________________________________

What do you believe?

What do I believe?

- Gifted individuals form a group that can be identified early in their school career and remains the same over time.

Agree Disagree - Gifted individuals are born with high intelligence.

Agree Disagree - Gifted and talented children need different forms of teaching and support from other children.

Agree Disagree - Because of their differences gifted children need to be educated separately from other children.

Agree Disagree - Teachers need special training and skills to teach gifted children.

Agree Disagree - Giftedness is genetic and cannot be changed.

Agree Disagree - Gifted and talented children need competition to keep them on their toes.

...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables and Diagrams

- About the author

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 Gifted children in the primary classroom

- 2 Principles of good practice for all learners

- 3 Asking better questions

- 4 The menu approach

- 5 Managing whole class research projects

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index