![]()

1

The Development and Use of Diaries

The inescapable duty to observe oneself: if someone else is observing me, naturally I have to observe myself too; if none observes me, I have to observe myself all the closer.

Franz Kafka, 7 November 1921

Key aims

- To outline the ways in which diary keeping has developed and key features of diaries.

Key objectives

- To define what a diary is.

- To examine the development and evolution and consider the conditions underpinning the development of diary keeping.

- To consider the publication of diaries and the different types of published diaries.

Definition of diaries

A diary can be defined as a document created by an individual who has maintained a regular, personal and contemporaneous record. Thus the defining characteristics of diaries include:

- Regularity A diary is organised around a sequence of regular and dated entries over a period of time during which the diarist keeps or maintains the diary. These entries may be at fixed time intervals such as each day or linked to specific events.

- Personal The entries are made by an identifiable individual who controls access to the diary while he or she records it. The diarist may permit others to have access, and failure to destroy the diary indicates a tacit acceptance that others will access the diary.

- Contemporaneous The entries are made at the time or close enough to the time when events or activities occurred so that the record is not distorted by problems of recall.

- A record The entries record what an individual considers relevant and important and may include events, activities, interactions, impressions and feelings. The record usually takes the form of a time-structured written document, though with the development of technology it can also take the form of an audio or audiovisual recording.

The precise form of diaries varies. The simplest form is the log that contains a record of activities or events without including personal comments on such events. Such personal logs are similar to ‘public’ journals such as ships’ log-books which are regular-entry books whose completion is ‘a task, whether officially imposed or self-appointed, performed for its public usefulness’ (Fothergill, 1974, p. 16). More complex diaries include not only a record of activities and/or events but also a personal commentary reflecting on roles, activities and relationships and even exploring personal feelings. The diarist may explicitly address different audiences. Elliott (1997, para. 2.2) suggests that diaries whose prime audience is the diarist should be classified as intimate journals, whereas diaries intended for publication and posterity should be classified as a memoir. Such a distinction is difficult to maintain. For example most of the entries which Gladstone, the Victorian politician, made in the diary which he kept for over 71 years were:

Lists of the persons written to, persons seen, places visited, meetings attended and works read. Once a week or rather more often, Gladstone added a sentence of comment about some individual, event or book, or his own reactions. More rarely he wrote a paragraph, usually of soul-searching. (Beales, 1982, p. 464)

The distinction between intimate journals and memoirs implies that it is possible to clearly discern the motivation of diarists. However it is difficult to make a clear differentiation between private or personal and public. MacFarlane suggests that the term ‘diary’ can be used for all personal documents which individuals produce about themselves, and uses the term:

as an all-embracing word [which] includes autobiographies. Often a ‘diary’ is nothing more than some personal observations scribbled in the margins of an almanack. (1970, p. 4)

The development of diaries

Diaries in their modern form developed in the early modern period in Europe. However there are texts which have some of the features of diaries that predate these by over 500 years.

Japanese ‘diaries’ and Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

The diary-like documents which predate the development of modern diaries in sixteenth century Europe were produced by literate elites, members of the Japanese Emperor’s court and European monks in mediaeval monasteries.

JAPANESE ‘DIARIES’ By the tenth century courtiers at the Japanese Emperor’s court had acquired sufficient expertise in writing to create a vernacular literature. Among the literature which has survived from this period are a number of so-called diaries, including Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book (Morris, 1970) and Murasaki Shikibu’s diary (Bowring, 1982).

Since the original documents no longer exist, the versions that survive were based on copies which in the case of Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book date from the mid thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries (Morris, 1970, p. 12), and it is difficult to be certain about the original content, structure and purpose. Sei Shonagon recorded how in the year 994 the Emperor gave her a gift of paper which she used to record ‘odd facts, stories from the past, and all sorts of other things’ (1970, p. 11). In contrast, Murasaki’s diary appeared to have been written as a record for a third person. Some sections had a letter-like form and there were also references to a third person.

Both texts contained accounts of events that can be clearly dated. In section 82 of the Pillow Book (dated to the tenth month of 995) Shonagon records the behaviour of the young Emperor Ichijo on his return from his first independent visit to a shrine dedicated to the god of war, Hachiman:

When the Emperor returned from his visit to Yawata, he halted his palanquin before reaching the Empress Dowager’s gallery and sent a messenger to pay his respects. What could be more magnificant than to see so august a personage as His Majesty seated there in all his glory and honouring his mother in this way? At the sight tears came to my eyes and streamed down my face, ruining my make-up. How ugly I must have looked. (1970, p. 11)

THE SAXON CHRONICLES In Europe writing skills were developed among and monopolised by the clergy, especially scribes in monasteries. In England these scribes used calendars to maintain a record or chronicles. When Saxon monks in preconquest England had to plot the date of Easter, they produced booklets with a line or two for each year and these were filled with ‘what might be considered significant events to the institution or locality in which the document was maintained’ (Swanton, 2000, p. xi). For example in a surviving set of Easter tables drawn at Canterbury Cathedral covering the years 988 to 1193 a scribe has recorded that in 1066 ‘Here King Edward passed away’, and a later hand added ‘and here William came’ (2000, p. xiii).

In its essence the form resembles a diary whose entries were made year by year instead of day by day. It could serve as a repository of the simplest statements of fact, demanding of the compilers no more than a knowledge of writing and of the facts to be recorded, yet at the same time it offered ample scope for a writer who wished to give a detailed account of the events of his day and perhaps even to make his own comments upon them. (Hunter Blair, 1977, p. 352)

These records formed the basis of the Saxon Chronicles which have literary as well as historical interest. For example the victory of the Saxon King Athelstan over the combined Viking, British and Scottish armies was recorded in a poem in the entry for the year 937 in the Parker Chronicle.

In this year King Athelstan, lord of warriors,

Ring-giver of men, with his brother prince Edmund,

Won undying glory with the edges of swords,

In warfare around Brunanburh.

With their hammered blades, the sons of Edward,

Clove the shield-wall and hacked the linden bucklers,

As was instinctive in them, from their ancestry,

To defend their land, their treasures and their homes,

In frequent battle against each enemy. (1977, pp. 88–9)

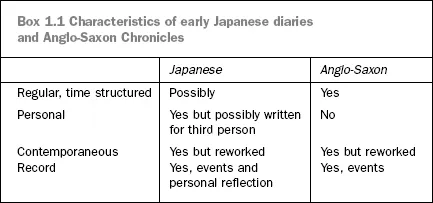

SUMMARY Both the Japanese ‘diaries’ and the Saxon Chronicles lacked the full characteristics of modern diaries. Japanese diaries contained both personal accounts and reflections but lacked the clear time structure of modern diaries. While the Saxon Chronicles did form a regular record of contemporary events, they lacked the personal and intimate characteristic of diaries and it is not clear that they were kept contemporaneously.

Development of the diary form in the early modern period

Diaries emerged as a recognisable method of keeping personal records in the early modern period in sixteenth century Europe. In England the young Protestant King, Edward VI, kept a Chronicle. It appears that he began the Chronicle as an educational and formal exercise for his tutors when he was about 12 years 5 months. Within a year or so it became more personalised and informal in style and he maintained it till shortly before his premature death at the age of 15 (Jordan, 1966, pp. xvii–xviii). The Chronicle was a record of events and contained little commentary. For example on 2 May 1550 Edward VI recorded the first execution for heresy in the reign, Joan Bocher, an Anabaptist:

[May, 1550]

2. Joan Bocher, otherwise called Joan of Kent, was burned for holding that Christ was not incarnate of the Virgin Mary, being condemned the year before but kept in hope of conversion; and 30 of April the Bishop of London and the Bishop of Ely were to persuade her. But she withstood them and reviled the preacher that preached at her death. (Jordan, 1966, p. 28)

By the seventeenth century, diary keeping had become an established mechanism for keeping personal records and there was a rapid expansion of the form (MacFarlane, 1970, p. 5). An increasing number of diaries survive from these periods. The most famous were those kept by Samuel Pepys (whose main diary covers the period 1660 to 1669) and John Evelyn (covering his whole lifetime from 1620 to 1706). Diaries were also kept by Robert Hooke, the scientist and architect; John Ray, John Locke and Celia Fiennes, who recorded their travels; Anthony Wood, who recorded university events; John Milward and Anchitel Grey, who recorded parliamentary debates; and Ralph Josselin, who recorded the events of a village from the perspective of a Puritan parson (Latham, 1985, p. xxxv).

The development of diaries during this period was underpinned by technological and socio-economic changes. The technological changes included the widespread development of writing skills in vernacular languages and the production of ready-made almanacs. The socio-economic changes included the fragmentation of Christianity in Western Europe and the rise of Protestantism with its greater emphasis on individualism and the changes associated with the rise of capitalism.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS UNDERPINNING THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIARIES The main precondition for the development of diary keeping in the seventeenth century was improved access to writing. Prior to the development of modern technologies such as mass production of paper and writing implements such as pens and pencils, writing was a complex and expensive technology restricted to an elite who were specially selected and trained. The difference between the language used for writing and the vernacular language used for everyday communication created an additional barrier to wider access to writing. In mediaeval Western Europe, the written language used by the Church and for international contact was Latin. Reading and writing were taught in schools associated with monasteries and cathedrals, some of which developed into universities (Janson, 2002, p. 168).The changes associated with the Refor...