- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communicating Health and Illness

About this book

`There has been a pressing need for a book like this for some time. Gwyn cogently reviews the literature on discourse analysis as it pertains to medical and health matters. Introducing original research from his own studies allows him to vividly illustrate just how important it is to understand the role played by discourse. Students of health communication and the sociology of health and illness will find this book integral to their studies? - Deborah Lupton

In this book, Richard Gwyn demonstrates the centrality of discourse analysis to an understanding of health and communication. Focusing on language and communication issues he demonstrates that it is possible to observe and analyze patterns in the ways in which health and illness are represented and articulated by both health professionals and lay people.

Communicating Health and Illness:

Explores culturally validated notions of health and sickness and the medicalization of illness.

Surveys media representations of health and illness

Considers the metaphoric nature of talk about illness

Contributes to the ongoing debate in relation to narrative based medicine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Communicating Health and Illness by Richard Gwyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Body, Disease and Discourse | 1 |

Illness is constructed, reproduced and perpetuated through language. We get to know about our own illnesses through the language of doctors and nurses, friends and relatives, and we often recycle the words picked up from our consultations in the doctor’s surgery into conversation, sprinkling our stories of sickness with epithets that give the impression of a grander knowledge of medical science. When we open the newspapers or switch on the television or radio, we encounter an increasing variety of articles and programmes offering information, advice and warnings about every conceivable dimension of health and care of the body.

This concern with health issues is not new, but has never before been so omnipresent. We are saturated with health issues. We live in an era obsessed with health and fitness, in which ‘perfect health’ is seen to have its corollary in ‘total fitness’. Advertisements, television programmes and films discharge a constant stream of images and models upon which we style our bodies and appearance. Advertising, for the main part, still relies on the human body to sell products. Beautiful, flawless models hawk healthy produce from billboards and TV screens. In these advertisements, a perfectly healthy body implies a kind of immortality in the moment, a defiance of death (cf. Bauman, 1992) or else flight from the insufferable workaday present into a state of perpetual happiness (or its correlative in ‘real’ time, the holiday). The current era, it has been said, is dedicated to the body project (Turner, 1984; Featherstone, 1991; Lasch, 1991; Shilling, 1993) in which millions of people throughout the affluent world strive to acquire toned muscles, to discard unwanted fat, to style their bodies just as they might style their hair; with new breasts, new buttocks, new noses – and all this external remodelling is quite apart from the steady and persistent growth in the market for internal organs of every kind. An illusory ideal of ‘perfect health’ is more and more being regarded as the norm, the undisputed prerogative of an unmarked version of humanity; and any hint of waywardness or defect, variance from established norms of weight or shape, deformity or disfiguration, is perceived as a type of deviance, indicating a marked and a lesser humanity.

Alongside the proliferation of discourses of health and illness are new terms which a generation ago either did not exist or else were entirely unknown to most people, such as PMT, ME and HIV, not to mention ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder) and PTS (post-traumatic stress), terms which are now normal currency. These and other acronyms reflect a sense of the ever-growing territory claimed by the medicalization of language. For some earlier writers, such as the medical anthropologist Friedson (1970), a consequence of this ever-encroaching medicalization are that socioculturally induced complaints and syndromes were being wrongly redefined as ‘illness’. This is an idea pursued at greater length by Showalter (1997), who argues that certain contemporary afflictions, ranging from chronic fatigue syndrome to alien abduction, are specific manifestations of a widespread cultural hysteria.

Medical terms are scattered throughout our conversations, and a much wider knowledge of terminology is discernible in everyday discourse than existed even a generation ago. One of the effects of this medicalization of language is to legitimize positions on topics about which even so-called experts actually know very little. In addition, there often appears to be little in the familiar world which is not either directly damaging to health or else suspected of containing carcinogenic agents. Recent debates in Britain on issues surrounding BSE-infected cattle and GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) in food have emphasized most clearly the paradox that basic ‘life-giving’ foodstuffs such as bread might contain the ingredients for long term, and possibly irreversible, damage to human health.

In this chapter, then, I will consider the impact of medicalization on contemporary lives by examining various discourses on the body and embodiment, before moving on to discuss accounts dealing with the essentially external or ‘exogenous’ provenance of disease. It will be seen that along with the ‘reification of the body’, there has arisen a concomitant reification of disease and of medicine. The chapter concludes by considering the term ‘discourse’, its permutations in academic texts, and the importance to the current study of a discourse analytic perspective.

THE QUEST FOR TOTAL HEALTH

Health is by no means the ‘natural’ state of human beings, even if it is the preferred one. What might be considered a reasonable expectation – relative freedom from disease – is quite a different thing from the kind of ‘total health’ on offer from the thousands of outlets now selling ways to keep fit and stay young-looking. The World Health Organization’s definition of health as unimpaired mental, physical and social well-being is little more than a dream to most of the human race. The more illnesses that are ‘wiped out’, the more versatile and virulent their successors. The costs of running the medical machine, with its emphasis on sophisticated equipment and ever more refined means of electronic surveillance, are astronomical. The metaphorical conceptualization of ‘the war against disease’ (Guggenbühl-Craig, 1980) is, in the eyes of the medical establishment, a perfectly appropriate one. For the researchers and medical practitioners involved the ‘war’ is a reality:

During the last century and a half, the vanguard of medical science has experienced one triumph after another. Disease, its fiendish adversary, twists and turns, writhing under the blows of the healers’ swords, attempting to avoid its total eradication. On the other hand, doctors are busier than ever. Medical costs are rocketing ... Each new technique, each new machine demands more money: weapons are expensive, and wars are costly undertakings: ‘What does that matter?’ we ask. ‘The important thing is to win!’ We wait with bated breath for the long-promised victory. (Guggenbühl-Craig, 1980: 7)

Since the early 1970s there has been a growing awareness of, and opposition to this medicalization of society, reflected in the passage I have just quoted. Critics such as Zola (1972) described what they perceived to be a cultural crisis in modern medicine, of health care systems which were expensive, over-bureaucratized, inequitable and ineffective (Lupton, 1994a: 8). Illich (1976) argued that modern medicine was both physically and socially harmful due to the impact of professional control, leading to dependence upon medicine as a panacea, obscuring the political conditions which caused ill health and removing autonomy from individuals to control their own health.

In the dialectics of contemporary public health, much is made of the ‘responsibility’ of the individual for his or her health, but what does this actually mean? According to Lupton (1994a: 32), disciplinary power is maintained through a range of screening procedures, fitness tests and through health education campaigns which set out to invoke guilt and anxiety in those who do not follow a prescribed behaviour. The rhetoric of public health obscures its disciplinary agenda since health is presented as a universal right and a fundamental good. Campaigns aimed at encouraging individuals to change their behaviour, and to minimize risk taking, are therefore regarded as wholly benevolent.

THE SOCIALLY CONSTRUCTED BODY

My argument in this chapter arises out of the confluence of two mutually supportive types of discourse: discourses of the body and discourses of medicine. It is often difficult to consider either of these topics, the body and medicine, without reference to the other, since our contemporary view of the body has become thoroughly medicalized. Medicalization is a term originating from the constant exposure of human bodies to the ‘medical gaze’, a phenomenon described by Foucault (1973), which now appears to radically underscore perspectives on the human body, so that no newspaper is without its almost daily quota of articles and advice columns on health care, quite apart from the substantial literature in specialist ‘health and fitness’ magazines, websites and TV programmes.

With this in mind, it is worth examining the role of the body in the contemporary world, and the conflicting and uncertain nature of discourses surrounding it. In respect of this, Shilling, a leading theorist of the body, has written:

We now have the means to exert an unprecedented degree of control over bodies, yet we are also living in an age which has thrown into radical doubt our knowledge of what bodies are and how we should control them. (Shilling, 1993: 3)

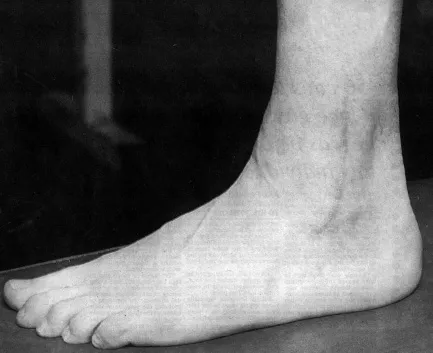

A considerable burden of blame for the uncertainty or doubt with which many individuals regard their own bodies can be laid on the medicalization of society. A notable device by which a medicalized view of the body is reflected in cultural representation is the ‘body as machine’ metaphor. This presents the body as ‘radically other to the self’ (Shilling, 1993: 37). People are encouraged in government health promotion schemes and health product advertising to care for their bodies as they would care for pieces of machinery. A clear illustration of this is in the way the media cover the details of injuries to sports personalities and other famous people. In sport, especially, the body is regarded as a complex machine whose performance can be enhanced, and which can be repaired, just like any other machine. The injuries of sportsmen and women are frequently presented to us in the newspapers either photographically or in diagrammatic form so as to provoke easily understandable comparisons with pieces of machinery; incidentally, this creates totally unrealistic expectations of the recuperative powers of the body.

FIGURE 1.1 Welcome back:The left foot and lower leg of Welsh rugby player leuan Evans following surgery to ankle after suffering ‘horrendous injury’ (Westen Mail, 18 February, 1995; courtesy of the BBC)

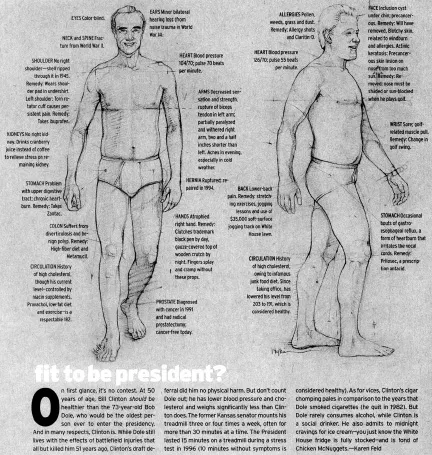

The body as machine metaphor was nicely demonstrated in an American political magazine before the US presidential elections in 1996, in which the various physical ‘flaws’ of the two candidates were displayed in the form of line drawings of Clinton and Dole, followed by a brief summary of their comparative health status and vices. The two candidates are depicted in a walking posture, Dole head-on, and Clinton in profile. Both men are smiling, and clad only in underwear. Particular physical frailties are signalled with marker lines and circles, and captions are attached, summarizing that debility and its treatment. Apart from the detailed knowledge that the magazine claims to have of the two contestants’ personal medical status (for example that Dole clutches a gauze-covered wooden crutch by night or that Clinton’s blood pressure is 126/70) there is a use of technical language which encourages a reading of the text in a way that endorses the ‘body as machine’ metaphor. We are told, for instance, that Dole ‘suffers from diverticulosis and benign polyp’ (treated by a high-fibre diet and Metamucil), while Clinton has occasional bouts of gastro-oesophageal reflux, which he treats with Prilosec. The inclusion of the specialist medical terms as well as the brand name of medicines in their treatment provides a setting within which each ‘malfunction’ has a specific treatment or remedy. The effect of this is to promote an understanding of the body in which component parts (i.e. pieces of machinery) can be treated or modified in order to achieve adherence to a normative ideal, namely that of the unblemished body.

Both Shilling (1993) and Frank (1991, 1995), claim there are two major contemporary viewpoints on the body, exemplified by the post-structuralism of Foucault and his followers (indicating that bodies are controlled by discourses); and by the symbolic interactionist stance of Goffman. Shilling claims the differences between the two positions are not as great as might at first appear. This is because both theorists hold to a view of the body as being central to the lives of embodied subjects, while at the same time suggesting that the body’s significance is dependent on social ‘structures’ which exist independently of those individuals (1993: 71). While not wishing to become entrenched in theories of the body, which provide the input for at least one specialist journal, Body and Society, and at the risk of neglecting other pertinent, but largely derivative theories, such as that provided by Turner (1984), I will briefly discuss the ideas of Foucault and Goffman, both of which seem to be to be central to a social constructionist understanding of health discourse and health communication studies.

FOUCAULT, THE BODY AND POWER

For Foucault, and for the many scholars he has influenced, the body is ‘the ultimate site of political and ideological control, surveillance and regulation’ (Lupton, 1994a: 23). Since the eighteenth century, he claims, the body has been subjected to a unique disciplinary power. It is through controls over the body and its behaviours that state apparatuses such as medicine, schools, psychiatry and the law have been able to define and delimit individuals’ activities, punishing those who violate the established boundaries and maintaining the productivity and political usefulness of bodies.

FIGURE 1.2 Fit to be President? (Clinton/Dole Illustration from ‘George’ Magazine, 1996)

The Foucauldian approach to the body is characterized, first, by a substantive preoccupation with those institutions which govern the body and, secondly, by an epistemological view of the body as produced by and existing in discourse. Bodies which were once controlled by direct repression are, in contemporary societies, controlled by stimulation. Thus the body in consumer culture is coerced into a normative discourse (‘Get undressed – but be slim, good-looking, tanned’, as Foucault reminds us). Bodies, for Foucault, are ‘highly malleable phenomena which can be invested with various and changing forms of power’ (Shilling, 1993: 79).

Foucault regarded human history as falling into broadly defined epochs which are characterized by dominant discourses. These tracts of historical/discursive time he termed ‘epistemes’. According to the medical sociologist Armstrong, the current episteme, of which we are a part, in which human anatomy is still regarded very much as it has been since the publication of Gray’s Anatomy in 1858, will one day close, perhaps rendering the knowledge of Gray’s Anatomy as redundant as an eighteenth-century doctor’s discussion of ‘humours’ entering the body would be to a contemporary physician educated to believe in invasive bacteria.

Why, Armstrong asks, did people in the eighteenth century and earlier not perceive that disease could be isolated in organs and in body tissues? Why did they fail to realize that death comes from disease within the body rather than as a visitation from uncontrollable external forces? He answers as follows: ‘What is today obvious was then unknown because in the past the world was not seen according to Gray’s Anatomy’ (Armstrong, 1987: 64). Because we cannot see or measure the ‘humours’ which were said to inhabit the body, must we dismiss them as mistaken? Or, following Foucault, can we simply accept that they represent a different and incommensurable vision of the body and of reality?

The activity of power in the doctor-patient relationship is treated in the broader context of its historical development in Armstrong’s analysis. In this way he invokes several of the themes familiar from the work of Foucault. In Discipline and Punish (1977) Foucault writes that in the pre-modern era the sovereignty of kings demanded that power be overt, that (for example) a threat to the body of the king be punished with a display of raw and brutal power, the marking of one body by another (brandings, floggings, hangings) symbolizing the power of the sovereign over his subjects. Displays of power were evident wherever the sovereign passed, and castles, fortresses and regal ceremonies were ubiquitous manifestations of that power. At the end of the eighteenth century a new symbolic power emerged, which Foucault calls disciplinary power. This was symbolized precisely by the panopticon, a device designed by Jeremy Bentham to supervise and observe in the prison, but applicable too in the barracks, the school, the workhouse, the hospital -anywhere indeed where a central authority wished to maintain control from a central position, gazing outward, while the subject, unseeing, could only contemplate his or her own incarceration. Disciplinary power in this mode was based on the principle of total observation. Foucault refers to the inversion of visibility because previously the subjects had gazed upon the person, the majesty, of the king and on his symbolic strength, and now the gaze was directed from the guard to the person imprisoned. By the very nature of the panopticon, the guard was unseen, faceless. And the guard, of course, was himself monitored and under surveillance.

For Armstrong the stethoscope is a symbol of power in ‘capillary’ (a term used by Foucault to identify the individual or minimal) form. Apart from being of obvious practical use it is, claims Armstrong, a ‘self-conscious emblem to mark out the figure of the doctor’ (1987: 70).

The prisoner in the Panopticon and the patient at the end of the stethoscope, both remain silent as the techniques of surveillance sweep over them. They know they have been monitored but they remain unaware of what has been seen or heard. (Armstrong, 1987: 70)

While there have been specific criticisms (Shilling, 1993: 80) that Foucault fails to engage with the body as a focus of investigation (rather than merely a topic of discussion) there is no questioning the extent of Foucault’s influence in both the sociology o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Key to Transcription Symbols

- Introduction

- 1 The Body, Disease and Discourse

- 2 ‘Lay’ Talk about Health and Illness

- 3 Power, Asymmetry and Decision Making in Medical Encounters

- 4 The Media, Expert Opinion and Health Scares

- 5 Metaphors of Sickness and Recovery

- 6 Narrative and the Voicing of Illness

- Conclusion

- References

- Index