- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Identities in Talk

About this book

`Identity? attracts some of social science?s liveliest and most passionate debates. Theory abounds on matters as disparate as nationhood, ethnicity, gender politics and culture. However, there is considerably less investigation into how such identity issues appear in the fine grain of everyday life.

This book gathers together, in a collection of chapters drawing on ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, arguments which show that identities are constructed `live? in the actual exchange of talk. By closely examining tapes and transcripts of real social interactions from a wide range of situations, the volume explores just how it is that a person can be ascribed to a category and what features about that category are consequential for the interaction.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

| 1 | Identity as an Achievement and as a Tool |

| Charles Antaki and Sue Widdicombe |

This book is about identity, of course, but browsing readers who flip through its pages might wonder at the presence of so many lines of transcribed talk, often laced around with a filigree of curious symbols. What has talk got to offer us, they will ask, in trying to understand identity? Are the contributors recommending that we ask people to tell us who they are, and treat them as informants about what identities they have, and about what those identities lead them to think and do? No, it is not that. The contributors to this book do not want to treat people as informants, nor do they want to interpret what people say, still less speculate on the hidden forces that make them say it. Rather, they want to see how identity is something that is used in talk: something that is part and parcel of the routines of everyday life, brought off in the fine detail of everyday interaction.

An Ethnomethodological and Conversation Analytic Perspective on Identity

The chapters of the book are informed by the general ethnomethodological spirit of treating social life as the business that people conduct with each other, displayed in their everyday practices. We use the permissive phrase ‘ethnomethodological spirit’ (and the rather vague term ‘everyday practices’) because to do so tolerantly allows common ground in people’s increasingly various recommendations as to just how to go about doing this sort of analysis. What is common to all the contributors to this book, at least, is the early ethnomethodology of Harold Garfinkel (1967) – to distil it brutally, his notion that social life is a continuous display of people’s local understandings of what is going on – and its conversation analytic crystallization in Harvey Sacks’s insight that people accomplish such local understanding by elegantly exploiting the features of ordinary talk. Every contributor takes those pioneers’ anti-mentalist and anti-cognitivist view of how analysis should proceed, and what analysis will reveal. Identity, in this view, and to use an ethnomethodological contrast, ought not be treated as an explanatory ‘resource’ that we as analysts haul with us to a scene where people are interacting, but as a ‘topic’ that requires investigation and sweat once we get there.

Identities in Practice

Once we are at a scene, the ethnomethodological argument runs, we shall see a person’s identity as his or her display of, or ascription to, membership of some feature-rich category. Analysis starts when one realizes that any individual can, of course, sensibly be described under a multitude of categories. You might say that that is hardly a good point of departure, since, obviously, most possible descriptions of a person simply are not true (neither of the book’s editors is Portuguese, very fat, has more than two lungs, and so on). But as the ethnographer-turned-conversation-analyst Michael Moerman put it, ‘the “truth” or “objective correctness” of an identification is never sufficient to explain its use’ (1974: 61; first published 1968). Something else – many other things – comes into play.

The interest for analysts is to see which of those identifications folk actually use, what features those identifications seem to carry, and to what end they are put. The ethnomethodological spirit is to take it that the identity category, the characteristics it affords, and what consequences follow, are all knowable to the analyst only through the understandings displayed by the interactants themselves. Membership of a category is ascribed (and rejected), avowed (and disavowed), displayed (and ignored) in local places and at certain times, and it does these things as part of the interactional work that constitutes people’s lives. In other words, the contributors to this book take it not that people passively or latently have this or that identity which then causes feelings and actions, but that they work up and work to this or that identity, for themselves and others, there and then, either as an end in itself or towards some other end.

The earliest explicit appearance of this programme is in Harvey Sacks’s very early work on the fundamental importance of people’s use of categories – of which an ‘identity’ category is a peculiarly protean sort – as a practical matter of transacting their business with the world. His lectures in the mid-1960s to early 1970s (as reproduced in Sacks, 1992) returned time and time again to the way people organized their world into categories, and used those categories – and the features that they implied – to conduct their daily business. Once Sacks had put these notions in the air, ethnomethodologists and conversation analysts went out to see how people use categorical work (which might be ascription, display, hinting, leakage and so on), with no commitment to any position on whether someone truly ‘had’ this or that identity category, or what ‘having’ that identity made them do or feel.

Five General Principles

All this is still rather up in the air, and wants bringing down to earth. Let us make a list of five things, gathered up from the literature since Sacks, which seem to be central to an ethnomethodological, and more specifically a conversation analytic, attitude to analysing identity. The list looks like this (and we shall explain the more abstruse-sounding expressions in a moment):

- for a person to ‘have an identity’ – whether he or she is the person speaking, being spoken to, or being spoken about – is to be cast into a category with associated characteristics or features;

- such casting is indexical and occasioned;

- it makes relevant the identity to the interactional business going on;

- the force of ‘having an identity’ is in its consequentiality in the interaction; and

- all this is visible in people’s exploitation of the structures of conversation.

We do not want to say that every analyst will favour all five principles equally, and all of the time. There is variety in, and sometimes outright warfare over, what can reasonably be called ethnomethodology or conversation analysis (see, for example, Graham Watson’s (1992) admirably non-partisan overview); but, trying to be ecumenical, we do want to say that getting a sense of how these five principles are used is to get a good flavour of the general ethnomethodological analytic attitude (as it is expressed, in varying strengths, by the contributions to this book). Now let us see if we can make a bit more sense of the unfamiliar terms above.

Categories with associated characteristics or features Certainly all contributors to the book would want to respect Sacks’s foundational work on membership categorization devices. Sacks made a great deal of what he saw as the absolute centrality, in human affairs, of people’s use of language to arrange and rearrange the objects of the world into collections of things. These collections (‘membership categorization devices’) – ‘the family’, say, or ‘middle-class occupations’ – would order together what would otherwise be disparate objects, or objects knowable under some other description. So casting person A, B, C and D as (say) ‘cabin crew’ unites them into a team and imposes on them a range of features which come along with that team-label (in Sacks’s term, they would now have ‘category-bound features’). They would now be flight attendant, bursar, first-class steward and so on, with cabin-crew attributes of being polite, knowledgeable about aircraft safety, well-travelled, and so on. But if you cast the very same people as ‘white-collar union members’, you dissolve any such job-specific implications and replace them with what is conventionally knowable about people who have joined a staff association; if you cast them as ‘British’, you allow them to pass through British immigration checks, without caring about whether they are in a union or not, and so on. A person, then, can be a member of an infinity of categories, and each category will imply that she or he has this or that range of characteristics. There is an important corollary to this: not only do categories imply features, but features imply categories. That is to say, someone who displays, or can be attributed with a certain set of features, is treatable as a member of the category with which those features are conventionally associated. If you look and act a certain way, you might get taken to be a flight attendant; if you have certain legal documents with certain appropriate authorizations, you can be taken to be British.

Indexicality and occasionedness The notion here, borrowed from linguistics, is that there is a class of expressions which make different sense in different places and times – ‘here’, ‘I’, ‘this’, and so on. What Sacks wanted to do with it was to extend its use to expressions of category membership – to say that they make different sense according to the company they keep. It is hard, he argues, to read a report that, say, ‘a thousand teenagers died in traffic accidents last year’ without taking it that the people referred to ‘are’ teenagers, even that they died in that way because they were teenagers, that teenager was the relevant category under which to describe them in those circumstances (as opposed, say, to ‘cyclists’, ‘pedestrians’, and so on, or – though this is tellingly hard to see – ‘people of various heights’ or ‘people who tend to watch a lot of television’ and other characteristics made irrelevant by the indexical context). Once we have that under our belt, we see also what he means by occasionedness: that any utterance (and its constituent parts) comes up indexically, in a here and now, and is to be understood so. In other words, a good part of the meaning of an utterance (including, of course, one that ascribes or displays an identity) is to be found in the occasion of its production – in the local state of affairs that was operative at that exact moment of interactional time. It might be, for example, that the classification of person Z as a ‘teenager’ is occasioned by the local environment of the interaction being a survey count of road-accident victims, with the participants looking for age information as they work their way through a series of dossiers full of information of all kinds.

Making relevant and orienting to It is probably true to say that a majority of the contributors would endorse some form of Schegloff’s (1991) powerful development of the Sacksian case that one should take for analysis only those categories that people make relevant (or orient to) and which are procedurally consequential in their interactions. Let us just unpack that a little. Make relevant and orient to are two bits of conversation analytic terminology which look rather off-putting, but their oddity makes memorable the notion that identity work is in the hands of the participants, not us. It is they who propose that such-and-such an identity is at hand, under discussion, obvious, lurking or ‘relevant to’ the action in whatever other way. It is they who ‘orient to’ something as live or operative, without necessarily naming it out loud – thus, I can ‘orient to’ what you just said as if it were a question, or as a statement, or as a joke, and so on; I can ‘orient to’ you as my father, an ex-public schoolboy, a successful businessman, and so on.

Procedural consequentiality That too looks rather fearsome, but again its very awkwardness is a useful signal that something is being marked off from more comfortably literal ways of describing who people ‘are’. Schegloff (1992) makes explicit (and vivid) the recommendation that we should take identities for analysis only when they seem to have some visible effect on how the interaction pans out. Put this together with relevance, and what you have is the discipline of holding off from saying that such and such a person is doing whatever it is he or she is doing because he or she is this or that supposed identity. It is, for example, holding off from saying ‘this person is a quantity surveyor’ until and unless there is some evidence in the interaction that his or her behaviour was, in fact, consequential as the behaviour of a quantity surveyor. It might well not be, if the scene we are looking in on is treated by the participants as being something where such information is entirely irrelevant: a religious service, say, or a hobbyists’ weekend. It is as well to realize the radicality of this move, as critics have pointed out and against which Schegloff defends himself (in, for example, Schegloff, 1997): it does mean holding off from using all sorts of identities which one might want to use in, say, a political or cultural frame of analysis (the fact that this participant is a man, or a Jew, or Dutch, and so on) until and unless such an identity is visibly consequential in what happens.

Conversational structures Once you are in another person’s sensory orbit, anything either of you does is up for interpretation as being meaningful for the other. What you do is a signal. But it is not like a lighthouse beacon, which simply shines at a given brightness and revolves at a given speed. Your demeanour – your talk – changes to fit something the other person does, and vice versa. The things which determine whether something fits, Sacks spotted, are tremendously powerful structural regularities in the way that talk is organized. A summons calls up a response, a question wants an answer, and so on. In his words, ‘“Conversation” is a series of invariably relevant parts’ (Sacks, 1992, Vol. I: 308; emphasis added). If you like, the point that Sacks is making is that these regularities hold sway whether the participants like it or not. Around a bridge table, once North has made a bid, East must follow, and what East says is understandable only given what North has just said. North’s bid ‘makes relevant’ East’s bid in a regular conversational structure that all the players play to. Indeed, once a bid has been made (or a question has been asked, a summons issued, and so on, to make the more general point), the regularity of what happens next is so powerful – so normative – that it is impossible for East not to declare a position, in some way or another. Even a grunt will be taken to mean something (presumably a rather ungracious ‘No bid’).

The point of this for our purposes is that such structures are generally there and available for anyone who speaks the language. Conversation is made up of regular structures of the bid-making and the question-answer sort (and those of overlap, interruption, repair, topic shift and the many more, both simple and complex, that you will meet in the body of the chapters of the book), all of which do some business or other. Indeed, conversation is so thick with such things that many people now follow Schegloff’s (1987) very useful recommendation and try to say ‘talk-in-interaction’ rather than ‘conversation’, if only to avoid the casual sense of talk as vague and inconsequential. The structures of talk-in-interaction are powerfully usable by anyone, at any time, so as to set a scene for the next turn at talk. Indeed they must be used; it is not the case that talk-in-interaction is a stream of largely inert gas with only the occasional surprise to wake people up. Every turn at talk is part of some structure, plays against some sort of expectation, and in its turn will set up something for the next speaker to be alive to.

A Worked Example

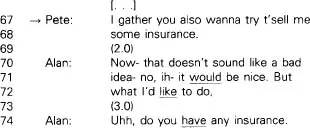

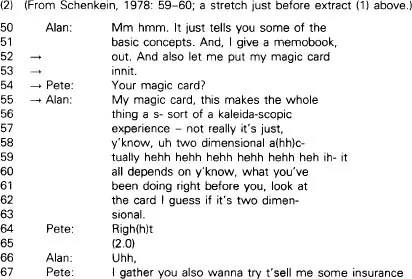

Let us try to illustrate the application of these five principles. Consider this strip of talk, and what Schenkein, in a classic of the conversation analysis (CA) literature on identity (Schenkein, 1978), has to say about it:

Pete’s utterance at line 67 is, according to Schenkein, an identity-rich characterization of Alan: it is an utterance which ‘draws upon a generally available description of the interests and practices of an abstract identity category like “salesmen” generally’ (Schenkein, 1978: 63.) This is a nice illustration of the very pervasive notion, originating with Sacks and visible in all the chapters in this book, that we mentioned above – that things can be shepherded together into collections, or categories, and that once there they take on the features associated with those categories. Here, that Pete is pigeonholing Alan as one of that set of people who are ‘salesmen’. It is worth labouring the point that it is not we analysts who are unilaterally saying either that ‘Alan is a salesman’ nor even that ‘Pete thinks that Alan is a salesman’ – it is a matter of us recognizing that Pete is treating Alan as a salesman, that Pete is ‘making relevant’ (or ‘orienting to’) this identity for Alan and for the interaction. The importance of the expression ‘treats Alan as’ (over ‘thinks Alan is’), let alone the unilateral ‘Alan is’ is that it keeps our eyes open to the possibility that what Pete is doing is not simply showing us what he thinks (whatever that means), but that his utterance might be designed actually to do something.

Now, what has gone on in the episode so far that will help us see what it might be that this making-relevant might be doing? To answer that is to show how Pete’s utterance is ‘occasioned’ – that is to say, fostered by the local business at hand. We pull back a little and see how the just-previous lines went:

Pete eventually gets to the familiar line (67) about Alan, but first look at the business of the ‘magic card’, because this is an excellent illustration of the principle that conversational regularities are wonderfully subtle resources to be exploited for identity work. Schenkein shows how Pete (in line 54) treats what Alan says as a puzzle, that is to say, something that in the circumstances wants some account. Indeed, Schenkein spots this as an example of a very general conversational sequence, which he calls the ‘puzzle-pass-solution’ sequence. You can see it in any stretch of talk where the first speaker’s turn includes something which the second speaker treats as a puzzle, obliging the first speaker to make intelligible what they originally said.

Alan might have used the sequence by putting the curious reference to a ‘magic card’ into the conversation – as a ‘puzzle’ – so as to elicit just that ‘pass’ reaction from Pete (‘your magic card?’), because that allows Alan to come up – in the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Transcription Notation

- 1 Identity as an Achievement and as a Tool

- Part I Salience and the Business of Identity

- Part II Discourse Identities and Social Identities

- Part III Membership Categories and their Practical and Institutional Relevance

- Part IV Epilogue

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Identities in Talk by Charles Antaki, Sue Widdicombe, Charles Antaki,Sue Widdicombe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.