![]()

| 1 | What is Educational Research? |

| | Clive Opie |

This first chapter seeks answers to the question in its title and a second one, ‘Can I do it?’. The answer to the first seems to require an exploration of various terminologies, for example positivism, interpretivist paradigm, ontology, epistemology, symbolic interactionism, action research, ethnography, grounded theory, critical theory and so on. Now, before these terms start to perhaps ‘blow your mind’ and you think about putting this text down, read on.

These terms, and the many others not mentioned, can, at first sight, seem baffling and complicated and only readily understandable by those who have been working in the area of educational research for many years. The truth of the matter is that to ‘do’ educational research at the Masters level one need only grasp a subset of such terms – and these are kept to a minimum and form the basis of this and the other chapters in this book.

This latter paragraph will undoubtedly raise eyebrows and criticism from some in the educational fraternity. What terms should be included? What criteria for their selection have been used? Why are those that have been excluded so treated? What is the validity (a term which will be explored more fully later in this book) for making these choices? One could, and rightly so, be criticised for a level of personal subjectivity in selection of the terminology deemed to be ‘appropriate’ at Masters level. Those chosen though are based on over a decade of experience of working with distance learning students and discussions with the colleagues who have worked with them in completion of their degrees. In this way the terminology presented here takes on a level of objectivity.

I would argue that in reality the majority of Masters students finish their degree blissfully unaware of much of the amassed educational research terminology, which exists. Should the educational research world be worried? Unless their student is undertaking a specific Research Masters designed as a prerequisite for a PhD as, for example, required by the recently introduced Educational and Social Research Council ‘1 + 3’ (ESRC, 2001) guidelines, then surely the answer has to be no. What is more important is that a Masters student, who, perhaps typically is not seeking to further their studies to a higher level (e.g. PhD), is aware of the main aspects of educational research terminology and crucially how these impinge upon the actual research they are seeking to undertake and the research procedures they need to employ.

To reiterate the context for this book is to provide a text, which meets the needs of beginner researchers. Limiting the terminology to be engaged with is one way of doing this. There are also numerous other eloquently written texts on the market, which more than adequately cover any ‘deemed missing’ terminology (Cohen et al., 2000; Walliman, 2001) should the reader wish to extend his or her knowledge of educational research terminology.

Having, I hope, indicated how I intend to answer the first of these two questions how about the second? This is much easier – the answer is yes – and hopefully you will come to this conclusion yourself as you work through this and the others chapters in this book.

Many of the chapters require you, the reader, to start from position of personal reflection. What do you think? What do you understand by? What are your views? This format is intentional as it begins to get you to explore various aspects of educational research from your personal perspective, knowledge and present understanding. You may, as some cultures do, feel this is relinquishing responsibility as a not uncommon view from those beginning research is that the MEd tutors are the experts so they should tell those less versed in this field what to do.

What this does though is deny the inherent knowledge and personal educational experiences, which any new researcher brings to the task. Experiences of working with children and colleagues, introducing and coordinating teaching schemes, reflecting on teaching problems, managing resources and the myriad of other day-to-day activities all add up to a wealth of knowledge which will almost certainly have some pertinence for any research being proposed. Where the MEd tutor is of value is in refining the research to be done and providing, as we shall see later, a systematic approach to its undertaking.

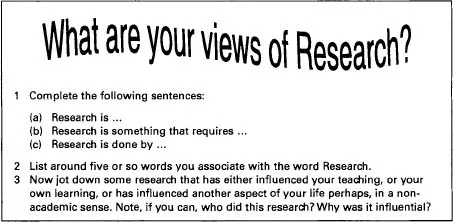

So, let’s start from your perspective of research, as shown in Figure 1.1. We shall not consider any answers to the third sentence(c) in Figure 1.1, although the normal paucity of answers, which usually occurs, is probably indicative of some of the issues we will raise in answering the first two. Hopefully though by the time we have worked our way through these you will have any worries about undertaking educational research dispelled, and realise you can do educational research.

What is educational research?

(a) Research is ...

Figure 1.1 Views of educational research

Seeking through methodical processes to add to one’s body of knowledge and, hopefully, to that of others, by the discovery of non-trivial facts and insights. (Howard and Sharpe, 1983: 6)

A search or investigation directed to the discovery of some fact by careful consideration or study of a subject; a course of critical or scientific inquiry. (OED, 2001)

You may not have arrived at such specific definitions but hopefully you will have begun to appreciate that research aims to overcome the limitations of ‘common-sense knowing’ (Cohen et al., 2000:3–5). You will undoubtedly have jotted down other terms such as ‘systematic process’ and concepts such as ‘control’ and we will address these later in this book. For now it is sufficient to keep the principle of the definitions above in mind. A lot of what will be written refers to social science research in its most general sense. But, as the social sciences cover a vast array of subject areas it is also worth providing a definition of educational research and its importance in the context of practising teachers, as it is these points we will be focusing on throughout this book. Educational research can then be viewed as ‘the collection and analysis of information on the world of education so as to understand and explain it better’, with a significance for practising teachers in that it should be

viewed as a critical, reflexive, and professionally orientated activity ... regarded as a crucial ingredient in the teacher’s professional role ... generating self-knowledge and personal development in such a way that practice can be improved. (Hitchcock and Hughes, 1989: 3–4)

(b) Research is something that requires ...

- the collection of quite large amounts of data

- results which can be generalised

- a hypothesis

- the undertaking of experiments

- objectivity rather than subjectivity

- the use of statistics

- that something is proved

- specific expertise, as it is difficult.

Those new to educational research often come up with answers not too dissimilar to those above. This list is not definitive and its order is no more than for convenience of this text, but it gives a fair picture of ‘typical’ views. None of them is necessarily correct although each will have its own significance depending on the kind of research being undertaken. Let us though look at each of these points in the context of the kind of research likely to be undertaken in the context of an MEd dissertation and the timescale within which to do it, typically six months.

Collection of large amounts of data

Educational research of the type involved at Masters level will be relatively small scale. This is not to say it may not have significant impact upon personal practice or that of others, or add ‘new’ knowledge to a particular field of enquiry. It will though in most cases not require the collection of large amounts of data – although again the definition of large is open to interpretation.

Typically one may be working with around two or three classes, say a hundred students maximum, but on the other hand research may centre on one’s own class of 20 to 30 students. Good dissertations (Lees-Rolfe, 2002) have also resulted from in-depth studies of just one student. What is not likely to happen (although I have had a few good MEd dissertations, against my advice, which have) is that research will be undertaken with hundreds of students or involve the collection of tens of thousands of pieces of data (Fan, 1998). Neither time nor access are usually available to allow this to be achieved and even if it does then the overall timescale for the research will almost invariably limit the analysis of it, which begs the question, ‘Why was it collected in the first place?’ (Bell and Opie, 2002).

Hopefully this last paragraph has shown that there is no definitive answer to the amount of data you might collect. This quantity, as it should be, will be determined by your research question, the methodology you choose to investigate it and the procedure(s) you select to gather the data to answer it. This may sound less than helpful but it reflects the realities of educational research. At the risk of being criticised by others more eminent in the field than myself, the following are guidelines based on my experiences with MEd students. Take them as guidelines though, as there are no hard and fast rules, and listen to your tutor’s words of advice.

If you are asking closed questions (see Chapter 5) keep the total number of data items obtained to no more than 2,000. This will give you around 20 data items per student, for your three classes of 30. This should be more than sufficient if you have defined your research question well. However, if some of these questions are open ended you are well advised to reduce the total number asked.

If you are undertaking interviews you might consider limiting these to no more than six people (less is acceptable); with no more than ten questions being asked; and to take around 45 minutes to complete. This may seem very small but just transcribing a 45-minute interview will take you a good two to three hours and then you’ll spend more time analysing your findings and collating views. Invariably your interview questions will have arisen from an analysis of a previous questionnaire so you have this data to analyse as well.

Results which can be generalised

Although there is no need to try and provide results which can be generalised, the findings may have important implications, either for personal practice or others working in similar areas. But, collecting large volumes of data in order that the educational research they stem from might provide useful generalisations is not necessary or, if one is really honest, even possible given the scale of research being addressed in this book. As Bassey notes, ‘the study of single events is a more profitable form of research (judged by the criterion of usefulness to teachers), than searches for generalisations’ (1984: 105).

Bassey draws a distinction between ‘open’ generalisations where ‘there is confidence that it can be extrapolated beyond the observed results of the sets of events studied, to similar events’ and ‘closed’ generalisations ‘which refers to a specific set of events and without extrapolation to similar events’ (1984: 111). He goes on to link the latter term with the ‘relatability’ (1984:118) of a piece of educational research, that is how can it be related with what is happening in another classroom. Perhaps the most telling comments by Bassey are that although ‘“open” generalisations are the more useful in pedagogic practice, they also seem to be the more scarce’ (1984:103). Perhaps the merit of any educational research is ‘the extent to which the details are sufficient and appropriate for a teacher working in a similar situation to relate his (or her) decision making to that described’ (1984:119). In short the relatability of the work is more important than its generalisability.

Hypothesis and undertaking of experiments

The third and fourth elements of our list of what research requires suggest the need to have a hypotheses and to undertake experimental work. These may seem essential to educational research, for as Walliman notes:

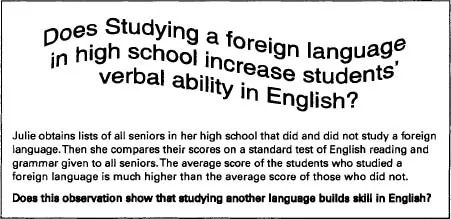

Figure 1.2 Problems of experimental research

A good hypothesis is a very useful aid to organising the research effort. It specifically limits the enquiry to the interaction of certain variables; it suggests the methods appropriate for collecting, analysing and interpreting the data; and the resultant confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis through empirical or experimental testing gives a clear indication of the extent of knowledge gained. (2001:174)

However, this technique of educational research suggests that the action of people can be controlled or conditioned by external circumstances; that basically they are the products of the environment they find themselves in. In this case thoughts, personality, creativity and so on, are irrelevant. You may like to think about this latter point in terms of your own personal development, working environment and culture. In so doing ask yourself if you have been conditioned to think or perform in a particular way or have you been the controller of your destiny? It is unlikely that you will come up with just one view as in reality this is dependent on particular situations and as these change over time you are likely to pitch your personal answer somewhere in between these extremes.

Look at the example in Figure 1.2, adapted from (Moore, 1997: 94), and before glancing at the answer decide for yourself what you think it might be and discuss it with others if you have the opportunity.

The answer to the question in Figure 1.2 is that it does not. Students will (in most cases at least) have decided whether to study a foreign language that is, it is their personal choice to do so, and for many of them they will already be better at English than the average student. So, these students will differ in their average test scores for English but there can be no suggestion that studying a foreign language has caused this (see Chapter 3 for more about the issue of causality). Moore goes on to indicate how Julie might undertake such an experiment but then highlights the impracticality and unethical nature of doing so.

Objectivity rather than s...