![]()

1

overtures

The ill-defined concept of ‘space’ itself presents an immediate problem. ‘What space is’ is of universal social interest and the topic of some of the most historic knowledge projects and texts produced by human cultures. How is space known? How might we take stock of our spatial knowledges, placemaking and spatial practices across cultures? What are the elements of a topology of space? If history and geography have a descriptive bias, a genealogy of space would go in a different direction, attempting to avoid describing within an unquestioned framework, while critically exposing the conditions for discourses on space and the framing effect of spaces. A ‘critical topology’ might take this even further, to ask how different formations or orders of spacing might coexist and not succeed but modify or warp each other. Borrowing from the insights of mathematics and theoretical physics, it would deploy a spatial method: a dynamic, set-based and topological rather than stratified approach. This book develops a ‘cultural topology’ as a critical theory and method for social science and geography by considering the recurrent quality of orders of spacing and placing – what I will call ‘spatialisations’. These will be presented as ‘virtualities’: intangible but real entities. Cultural cases, including the history of philosophies of space, will be used to illustrate the diversity of social spatialisations and their impacts. This chapter introduces social spatialisations by considering two historical cases, as presented in the ancient Chinese text, the Shan Hai Jing, and in the Kitab Nuzhat, an encyclopaedic atlas produced for Roger II of Sicily in the first half of the 1100s.

From the Shan Hai Jing to Herodotus’ Historiae and to Idrisi’s Kitab Nuzhat

The first geographers are mythographers then travellers; their books are histories then atlases. One of the first books, Shan Hai Jing, or The Guide to the Ways through Mountains and Seas, is a perfect illustration (P’o Kuo (Guo Pu), 1985). As a text it pre-dates not only books but printing. Though misinterpreted and embellished as a mythology by later generations, it was originally a book of geography describing the character of regions at the edges of the Zhou Dynasty empire (approx 1046–771 BCE) although elements are said to date from the first Hsia dynasty (twenty-second century BCE). Historians divide the text into a core ‘Classic of Mountains’ (Shan Jing) and later sections, ‘The Classic of Seas’ (Hai Jing) and ‘Classic of Great Wastes’ (Da Huang Jing). Divided into short passages, each entry describes locations grouped in geographical areas to present a comprehensive account of the world as the Warring States and the Han knew it. However, the places discussed are never sites of everyday life but mountains and distant regions where strange races and monsters dwell. They are metaphors of unknown hinterlands, the sorts of liminal zones discussed in Places on the Margin (Shields, 1991), and frontiers where social and cosmological order breaks down. Divinities, strange plants and hybrid beings populate an atlas of ‘interfaces between the animal, the human and the divine’ (Lewis, 2006: 285).

As a result, such writers as Sima Qian and Ban Gu1 dismissed the work as nonsense. In the earliest catalogue of Chinese texts it was classified under the section ‘Calculations and [Mantic] Arts,’ under the subcategory of ‘Methods of Forms’ (xing fa …) This category contains books on the physiognomy of men and animals as well as early examples of what would evolve into the science of environmental influence known as feng shui. The classification thus indicates that the Shan hai jing was viewed as a manual for divination based on the physical shape of the world … It may also reflect the fact that the text contains numerous accounts of natural prodigies and what they foretold.

In the twentieth century, the work was treated as a geography, a compendium of myths, an early ethnohistory, and a set of labels for lost illustrations [or maps]. A large literature has also attempted to gloss the places mentioned with modern or historical names. (Lewis, 2006: 285)

Spanning recorded history and the history of printed books, commentaries on Shan Hai Jing mirror change in successive dynasties (see Figure 1.1). Its classification changed in Chinese historiography between travelogue, strategic guide, bestiary and mythology, depending on the extent to which it was found to be useful to the Imperial court as an empirical reference in dealing with neighbours, its peripheries and foreign contacts. These included trade routes such as the Silk Road connecting China with the Middle East and Europe. Contemporary Chinese scholarship understands the text critically as a document dictating Imperial rituals binding the regions of Ancient China together. At the same time in contemporary China mountain parks and temples such as Wu Tai Shan (a key site in Buddhism) are being rediscovered as tourist and pilgrimage destinations for Chinese citizens.

Following Dorofeeva-Lichtman, Lewis argues that none of these classifications exactly capture the basic nature of the text as a cosmology which assigns every being and even ancient legend to a place in a sacred geography (Dorofeeva-Lichtmann, 1995).

The Shan hai jing, despite the impression given by the exact distances between sites, does not depict the world’s physical form. Instead it is a ‘conceptual organisation of space’ conveying fundamental ideals about the world through its overarching schema … the world [and cosmos] is square, oriented in the cardinal directions, balanced if not symmetrical … and clearly distinguished between centre and periphery … in which there is a progressive decline as one moves away from the centre through a series of concentric squares. (Lewis, 2006: 285)

Mountains in the Shan Jing are interfaces to the divine, distant seas of the Hai Jing are uncanny regions of strange beings ‘separated from the centre in both space and time’ (Lewis 2006: 285). History and geography are integrated into an atlas. The Shan Hai Jing is also a text integrated into the cults and politics of its time. Mountains are interfacial, in-between sites of spiritual potency where celestial and hybrid beings are expected. Distance equates with barbarism signalled by the monstrosity of the peoples. As Lewis notes, ‘remoteness … became part of an ideology of power’ (Lewis, 2006: 301). Peripheries are conflated with primitiveness and also with lesser-developed societies in a manner similar to the exoticism of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European ethnology and anthropology. Lewis argues:

the shift toward the horizontal dimension … focused on the distinction between inner and outer by structuring the earth according to the diverse peoples on its surface rather than the mountain chains that linked it to the sky. This shift away from the vertical is also marked by the abandonment as a structuring principle of the hierarchy from beasts through men to spirits marked by the relations of consumption and feeding. Instead it emphasized … beings sharing a common nature varied across space through the influence of custom. (Lewis, 2006: 295)

The Hai Jing and Da Huang Jing look not upward but outward to exotic peripheries. In part, the horizontal structure of the later sections coincides with the shift of attention to their borders and beyond by an expansive Han dynasty. However, these accounts are not detailed,2 but serve the self-definition of the Chinese (a strategy used throughout history (Lewis, 2006: 297)):

There is the state of the Zhi people. The god Shun sired Wuyin, who descended to the land of the Zhi. They are called the Shaman Zhi people. The Shaman Zhi people are surnamed Fen. They eat grain. They wear clothes that are not woven or sewn, and eat food that they do not plant or harvest. Here there are birds which sing and dance; simurghs that spontaneously sing and phoenixes that spontaneously dance. All varieties of four-legged creatures assemble here, and all types of grain can be gathered. (Lewis, 2006: 299)

This is also a processual itinerary similar to even more ancient Chinese legends such as the Yu Gong. As noted above, these texts are a prescription and model for the performance of actions that organise space (Lewis, 2006: 286), situating the reader and providing the basis for efficacious, strategic action. This is similar to annual royal processions of ancient Chinese rulers, ritual visits to mark sovereignty by making sacrifices on specific mountain tops, and seasonal duties in temple complexes which were followed as a means to authority (Lewis, 2006: 286).

Within the overall text known as the Shan Hai Jing, the Shan Jing is more empirical than the Hai Jing or Wan Jing. These appear to be written at different times rather than being one manuscript, although it was in its final form by the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). For contemporary Chinese scholars, the text is neither a unitary mythology nor a ‘cosmology’, even if it has been treated as such within China historically and by modern scholars outside of China. Chinese scholars have argued that the entire nature of mythology is different in China compared to Western Europe: it is not as closely articulated with everyday life but treated as an abstraction. It does not represent ‘mainstream’ historical Chinese cultural geography texts (such as the Confucian classics ShangShu (Book of Changes), Lifi (Record of Rites) or ShiJing (Book of Poetry). With its changing reception over time, it cannot be used as an atlas or index of historical events. For example, the Shan Hai Jing has no mention of Confucius or other historical figures. Nonetheless, the Shan Hai Jing provides an example of a text of rituals where the changing reception of the text over time suggests shifting ‘cultures of space’ or spatialisations.

Figure 1.1 Illustration from the Shan Hai Jing

Mediterranean Geographies

Although over 2000 years older, the Shan Hai Jing uses the same method as Renaissance and Islamic cosmographies that listed ‘marvels and curiosities under the place they were found and structured the presentation by moving from place to place while locating each site only in terms of the direction and distance from the preceding one’ (Lewis, 2006: 286). While previous theorists of space such as Lefebvre (1991b) have preferred a linear teleology in which one ‘mode of production of space’ (or reified spatialisations) surmounted the previous modes, these texts illustrate the absence of a linear historical development of spatial understanding, where history is full of reversions to older perceptions and never fully refuted conceptions of space. Hand in hand with this heterodoxy goes alternating social practices.

The widely travelled Athenian historian, Herodotus (Bodrum and Athens c.484–c.425 BCE), remarked on Hecataeus of Miletus’ (c.550–c.476 BCE) work Periegesis or Periodos Ges, ‘A Voyage Around the World’. Hecataeus’ world map was structured, like Miletus itself, on pure geometric forms (circles, squares), which influenced how the Earth was understood as a flat plane (Herodotus, 1962 IV: 36). These remarkable maps can be understood as diagrams – more like a subway map than the contemporary cartography we are used to. Our Mercator projection may one day be seen as just as distorting a representation as that of Hecataeus. Hipparchus and Ptolemy’s later concepts of latitude and longitude were related in part to an interest in defining Klimata – ecologico-ethnological regions (Ptolemy 1969) but became a coordinate structure. Bands of latitude were not only climatic, but were characterised by different flora, fauna and societies including different races of humans. This is one of the origins of the idea that a region’s inhabitants embody its qualities.

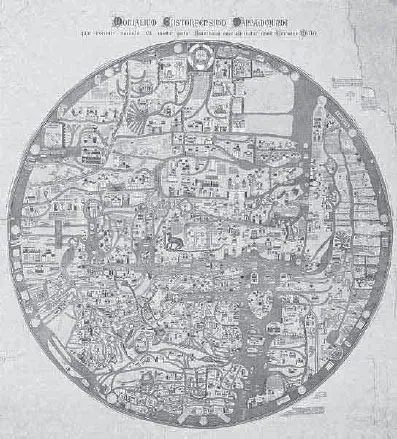

The maps included in the original edition of Ptolemy’s Geography have been lost. However, that barely matters. The text is absolutely lucid and can be read with profit even today … Ptolemy’s Geography was largely forgotten for many years except by a number of Muslim scientists. In Palermo, in the multicultural court of the Norman King Roger II, al-Idrisi (c. 1100–1165 CE) used an Arabic translation of the great work and improved on Ptolemy’s calculations. The Greek text was … not rediscovered until a Byzantine monk, Maximus Planudes (c. 1260–1330 CE), found a manuscript copy without the maps … This became the basis of the first printed Ptolemy atlas, which was published in Bologna in 1477 in an edition with five hundred copies. Columbus owned a copy and studied it carefully. (O’Shea, 2007: 15)

Figure 1.2 Mappa Mundi from Al Idrisi, Kitab Nuzhat, c.1154. This map is from a manuscript copied by Alî ibn Hasan al-Hûfî al-Qâsimî in Cairo in 1456, preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Mss. Pococke 375 fol. 3v-4). [Public domain, available on Wikimedia.org]

By the twelfth century, the most voluminous undertaking of its time with respect to knowledge was another geographical work, Al Idrisi’s encyclopaedic Kitab Nuzhat3 (Al Idrisi and Sezgin, 1988) commissioned by Roger II of Sicily from a team of famed twelfth-century scholars led by Al Idrisi (Ibn Rushd also known as Averroes). Idrisi is included in Raphael’s ‘School of Athens’ as the turbaned figure on the left (see Figure 3.). In effect, Roger II’s kingdom based in Palermo represented the intersection of feudal Christian and Moorish societies. The Kitab Nuzhat built on previous Arab geographical texts and experience but also involved teams that did fieldwork and gathered data. Although this masterwork was unknown in Europe until the sixteenth century, its organisation of research and its presentation as a narrative and cartographic representation of knowledge – including a large circular silver map (destroyed 1160) – were world views which influenced far more than cartographic practice. It inspired European global ambition and probably stories of it inspired Columbus. The Kitab Nuzhat anticipated the organisation of strategic state knowledge-enterprises in later centuries, from the Inquisition to the collecting and profiling practices of Napoleonic armies to Royal Commissions and state inquiries of our time.

Spatialisation and Space-Time

Geographies scaffold presuppositions about not only the world but the cosmos. Despite the official hesitation of dictionarians and philosophers, we find an unexpected cornucopia of spatial references embedding space and time in everyday life: elaborate expressions and elegant spatial metaphors. Not surprisingly, what appears to communicate most in slogans, theoretical description and ideological diatribes are precisely spatio-temporal allusions; they place us ‘in situ’ in innumerable, politicised, socio-spatial/socio-temporal contexts and in partisan relationships to other groups, individuals, objects, social processes and ideas, without necessitating the explicit enunciation of this partisan relationship. They place us in a space in which we are ‘to the Left’ or ‘to the Right’ of a political issue, for example, and in a time in which futures are presented before us as consequences of the present, or where we are asked to learn from the past, referring back and forth between tenses. In this, ‘space’ (and time) evidently plays an important role in knowledge and in knowing the world. It is political. When we turn to our daily speech, read the headlines of our newspapers, scan learned journals, we draw on our experience and understandings of spatiality and temporality.

Conceptions of space are intimately linked to those of time, and are intrinsic in the intellectual ordering of our lives and to our everyday notions of causality and experience. Time-space is very much the stuff of commonsense as well as physics. It spills over into practice. Presuppositions about the broad context we live in – that the world is flat or round, or that time is directed to a specific, teleological endpoint or simply unfolds as a trail of the present – form actions and responses to situations.

Is space not a cultural artefact in its own right, a socially produced framework which may become a self-fulfilling prophecy by structuring actions? Nearly every philosopher and soci...