![]()

Part I

Newpapers Past and Present

![]()

1

THE CONTINUING IMPORTANCE OF NEWSPAPER JOURNALISM

A newspaper’s role is to find out fresh information on matters of public interest and to relay it as quickly and as accurately as possible to readers in an honest and balanced way. That’s it. (Randall, 2007: 25)

So writes David Randall in his book The Universal Journalist, the much reprinted, all over the world, and excellent ‘insider’ book on journalism and what it takes to be a journalist. Randall loves journalism and newspapers, and unlike many manages to remain upbeat about both. He recognises the criticisms of both, and is intolerant of journalism that fails to meet his high standards, but he maintains that there is more good journalism than bad, and that there are more honest journalists than twisters of the truth. And he believes that journalism and newspapers can, and should, be an influential force for good, and often are. The authors of this book share that view, but also recognise that it isn’t the whole story. A newspaper’s role is fundamentally that put succinctly by Randall; and he enlarges on it:

It [a newspaper] may do lots of other things, like telling them [readers] what it thinks about the latest movies, how to plant potatoes, what kind of day Taureans might have or why the government should resign. But without fresh information it will be merely a commentary on things already known. Interesting, perhaps, stimulating even; but comment is not news. Information is. (2007: 25)

But beneath that lies a complex web of debates and issues surrounding and influencing that simple purpose. They involve the content of newspapers, how that content is selected and how it has changed over time; the economics of newspapers, who owns them and determines their policies, editorial and commercial; the threats to newspapers from competing media, even their survival; the extent to which society wishes to regulate or control newspapers, the freedom of a free press; the responsibility of newspapers with regard to matters such as privacy, taste and decency, the age-old contest between public interest and what interests the public. There are other issues currently being debated about the effects of the press we have (and deserve?) on public attitudes to politics and politicians, on the susceptibility of newspapers to the influence of an increasingly sophisticated public-relations industry, on whether newspapers are coping with declining sales by ‘dumbing down’, trivialising, or whether changes in the news agenda are simply a response to changes in society and its interests. An understanding of current preoccupations is informed by an awareness of how the press has developed over the centuries, a historical context. All this and more will be discussed in this book.

Newspapers not dead – shock

A newspaper has been described as a portable reading device with serendipity. You can take it anywhere and read it anywhere. You do not have to plug it in or recharge it. Newspapers remain fairly cheap; even the Sunday Times, Britain’s first £2 newspaper, costs no more than a pint of beer in most places, rather less than in some, and less indeed than the DVD that will inevitably be provided free in the polybag that holds all the sections together. For that £2, if you were as interested in property as cars, sport as fashion and style, culture as business, you would get as much reading as you could accommodate in a week of Sundays. At the beginning of 2009 the most expensive dailies (excluding the specialist Financial Times at £1.80) were the Independent at £1 and the Daily Telegraph, Guardian and Times at 90p (Monday to Friday), with the mass-circulation redtops half the price or less. The serendipity comes in the surprise. You can turn the pages and come across something you find interesting. You weren’t looking for it, because you didn’t know it was there and you didn’t know you would find it interesting.

The British have always been great consumers of news, comment and entertainment printed on paper, and we still are. We buy on average 11.2 million national newspapers each day and 11.8 million on Sunday (Audit Bureau of Circulations, October 2008). Readership of daily nationals is about 26.5million and Sunday nationals 28.3 million (National Readership Survey, average issue readership April 2008 to September 2008). Set against an over-15 population of about 49 million, that is a lot of newspaper reading.

There is no correlation between the popularity of newspapers and the extent to which they are criticised and abused. It is the ultimate love–hate relationship. Expressions like ‘Never believe what you read in the newspapers’ have entered the language and become clichés, usually uttered by people who, rightly, believe most of the facts they read in newspapers. They tend to absorb more of what they read than what they watch or listen to, and what they read in the newspaper makes a significant contribution to conversation in the home and workplace, a welcome antidote to last night’s EastEnders.

Despite (accurate) talk of the decline of newspaper sales in Britain, the fascination with them has never been greater. While debate goes on about the influence of newspapers over our national life, from politics to celebrity, the newspapers themselves are in the spotlight as never before. Politicians are to blame, for pandering to newspapers behind the scenes while in public attacking their malign influence on our national life. The public are to blame for buying the material they attack the newspapers for publishing, and for ‘shopping’ – and, in these days of mobile telephones doubling as cameras, photographing or filming – the misdemeanours of well-known figures they spot misbehaving. Newspapers themselves are to blame for their reluctance to admit their mistakes and excesses. Most dislike and disparage analysis and criticism of their practices, particularly when it comes from media academics. Rival media are to blame for deferring to newspapers and sustaining their reputation for remaining the most influential medium. So radio and television constantly review newspapers, rolling 24-hour news channels at length and repeatedly, with newspaper journalists doing it; current-affairs programmes discuss the content and views of newspapers, late-night phoneins discuss issues they have read about in the press; print journalists appear on Newsnight, Question Time, Any Questions, anywhere a view is needed. It is of course partly because the electronic media are obliged to be impartial whereas print journalists take positions.

None of this is good for the egos of the print journalists who are so magnified across the electronic media. They run the risk of taking themselves very seriously and believing in their own wisdom. Worse, they are susceptible to that dangerous disease, celebrity journalism. There was a time when print journalists were neither seen nor named. Now the newspapers give some of them lavish billing and television gives them a programme. The car is not the star on Top Gear; Jeremy Clarkson is. When Piers Morgan turns his charms on tabloid celebrities in his television interview show, there is no question who the real celebrity is. Not the WAG or supermodel. Both Clarkson and Morgan were once simply newspapermen.

So it would seem that despite accusations from some quarters that newspapers today trivialise and are dumbed down – and there is arguably some substance in both claims – newspapers have at least as much presence as they ever did. The basic role of the newspaper, to find things out and tell people about them, in as accessible a way as possible, is still fulfilled. There is debate about what those things that are found out are, and whether they are worth finding out in the first place (the news agenda), but it remains the case that without newspapers much that those exercising power over the rest of us would prefer not to enter the public domain does so through the medium of the newspaper.

Newspapers occupy a crucial place in the ‘public sphere’, defined by Habermas (1984:49) as ‘a realm of our social life in which something approaching public opinion can be formed. Access is guaranteed to all citizens’. Harrison (2006: 110) traces this public sphere for news from the conversations in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century town halls and coffee shops to the present era of newspapers, broadcasters and the internet. This engages the public in politics and debate. But today’s multi-media world is ‘increasingly provided by a smaller number of large and powerful organisations, as well as by organised and well-resourced groups in civil society’ (ibid.: 112). A decline in newspaper sales and an increasing concentration of ownership might undermine the access to a range of views.

Newspapers in the digital age

Journalism itself is more important than where its products are published, and one of the problems of the current media debate is the failure to distinguish between the two. So preoccupied have media owners and managements become with the process of publishing and the variety of opportunities modern technologies allow that debate over how and where to publish has drowned out the more important question of what to publish. The fashionable use of the generic word ‘content’ instead of news and information has a significance that goes beyond the semantic. Content is simply what occupies the space and to use it to describe the products of journalism is to devalue the spirit and practice of intellectual inquiry and analysis that is the hallmark of good journalism.

The debate over the future of newspapers and their place in a multimedia, multi-platform, converged media world is of course of great importance and fascination. It is crucial in a business sense because unless publishers make money they will not publish. But after a period of complacency – crisis, what crisis? – newspaper publishers realised that something had to be done. One or two titles – the Guardian for example, and for a short time the Telegraph – embraced, or at least acknowledged, the digital age before the turn of the twenty-first century. But many more decided to enjoy the profitability they were still experiencing, blink at the circulation figures and carry on doing what they knew how to do, produce newspapers. Managers and publishers had relatively recently come to terms with the post-Wapping benefits of the computer for newspaper production, and profits. They were slow to see that the computer would pose a much greater threat as a rival publishing technology. Most journalists felt equally unthreatened by those about them predicting doom, dismissing them as nerds and techies who never read anything anyway and preferred Apples to news. They could safely be left in ‘cyberland’ while real journalists got on with their newspaper reporting. As we shall see later, the newspaper mainstream, editorial and managerial, kept their heads in the sand and ignored the signs of change all around.

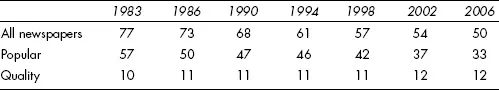

Table 1.1 Percentage of adult population reading a newspaper

Source: 24th British Social Attitudes Survey (2008)

Down and down: the decline of newspaper sales

Peter Preston edited the Guardian for 20 years from 1975 to 1995, and saw its circulation grow considerably over that period. Others did not have the same experience; decline had begun, and would accelerate. Reflecting on the general sales loss so preoccupying editors and owners today, Preston (2008: 642) describes the circulation falls over his professional life: thirty years ago the Daily Mirror selling 3,879,000, in June 2007 only 1,565,000. The Daily Express has fallen from 2,312,000 to 770,000, the Daily Telegraph from over 1.3 million to 892,000. ‘Where have 1.5 million News of the World customers gone? And over three million People readers. Why are national daily sales down to 11.6 million when those with not-so-long memories can recall 14 million? Why is our universe contracting year after year, as though inexorably?’

Franklin (2008a: 3) is less gloomy. ‘While the decline in newspapers’ circulations is undoubtedly significant, the suggestion here is that newspapers are not about to vanish or disappear’. Rather they are ‘changing and adapting their contents, style and design in response to the challenges they confront in the increasingly competitive market’. This is a world of other media platforms, the internet and mobile telephones. Franklin says this is not a ‘complacent’ argument, but a recognition that ‘adapting to increased competition, often driven by new technology, is historically what has triggered change in the newspaper industry .... what newspapers have always done’.

The latest (24th) British Social Attitudes Survey (2008) provides data on newspaper readership, and reviews how that has changed over the years of the survey’s publication. Regular readership (at least three days a week) is measured and divides newspapers into two categories, ‘quality’ (Times, Telegraph, Guardian, Independent, Financial Times) and ‘popular’ (Mail, Express, Sun, Mirror, Star). The figures in Table 1.1 show the percentage of the adult population reading any paper, a popular paper and a quality paper.

In their chapter of the Social Attitudes report Where Have All the Readers Gone?, John Curtice and Ann Mair (2008: 161–172) describe the decline as ‘continuous and relentless’, pointing out that regular adult readership of national newspapers in Britain has fallen from just over three quarters to just half. ‘Collectively Britain’s newspapers have lost a third of their readers and, instead of reaching the overwhelming majority of the population, are now regularly ignored by around half’. However, the authors note that readership of quality papers has remained steady at around one tenth of the population. ‘The overall decline in newspaper readership has in effect been a decline in the readership of (once) popular daily papers’.

It may seem strange to be producing a book on newspaper journalism at a time when the industry is dealing with declines in circulation and readership by trying to get away from the limiting ‘newspaper’ descriptor of its activities, and placing more emphasis on its non-newspaper activities. Words like ‘press’ and ‘newspapers’ are being removed from company titles, usually replaced with the word ‘media’ (Guardian Media Group, Telegraph Media Group). So obsessed are they with newspaper sales and readership decline, amplified by the advertising decline of the economic recession of 2008–09, so prepared to take seriously the apocalyptic soothsayers predicting the end of newspapers, that they seem almost embarrassed to talk about the newspaper bedrocks of their businesses.

But there remain good reasons for concentrating on newspapers in a book such as this, and they are not simply historical. The newspaper industry, perhaps because it is perceived by some to be the most threatened media sector, is a key driver in the change that is coming about. Newspapers, more than any other sector, are driving convergence by adopting other forms of publishing – web, audio, video. The broadcast sector, with its own problems of falling audiences through the fragmentation brought about by digital multi-channel opportunities, is not moving into newspapers. And online publishers of news are not moving into journalism, except those already in journalism: newspapers and news broadcasters.

So far the elephant in the room has been newspaper decline, or even death in the foreseeable future. Temple (2008: 206) suggests the newspaper is at ‘a critical crossroads, facing the most serious challenge to its future existence since the Daily Courant rolled off the presses in 1702’. Newspaper people have many strengths, but these often contribute to their weaknesses. They include looking on the dark side – bad news is usually bigger news; treating problems as crises; pessimism; and endless introspection. When journalists or media managers get together they seldom talk about anything but media matters. They also think in short time scales – after all newspapers come out every day or every week – so a set of poor circulation figures (despite the massaging to which the publishers have contributed) is a crisis not a problem. And a period of readjustment, albeit massive, is not the same as imminent death. Such panic attacks are not helped by an awareness that they were slow to wake up to the implications of online publishing, and when they did wake up it was in a state of hyperactivity.

It wasn’t as though circulation decline was a new problem. Newspaper sales have been in decline in the UK for 30 years, but to extrapolate that to the rest of the world, as Franklin (2008b: 307) points out, ‘articulates a curiously American and Euro-centric view of the press which seems blinkered to the explosion of new titles and readerships in other parts of the world’. Most people working in UK ...