![]()

| 1 | THE LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT OF LEARNING |

This chapter explores:

- The policy context for workforce development in social care

- The importance of the role of managers in social care in promoting professional and organizational learning

- Theories about leadership and its contribution to developing a culture of learning in social care

INTRODUCTION

In this first chapter, we will be setting the scene for the key topics explored throughout the rest of this book. The management literature has long established the importance of employee development as a managerial responsibility. However, some research indicates that few managers actually regard themselves as a key person responsible for facilitating learning (Ellinger and Bostrom, 2002). This may be because managers either lack skills in this area or perceive staff development to be a distraction from the ‘real’ work. Managers are often not rewarded or recognized for staff development activities or it is assumed that this is the sole responsibility of staff in their human resource or training departments. Arguably, all workers in health and social care have at least two learning related roles: first, in managing and engaging in their own learning, and secondly, in supporting the learning of others (Eraut, 2006). While managers would appear to have more direct responsibilities for managing the learning of others, we must also recognize that most learning is an important, albeit unrecognized, by-product of work itself and is the essence of professionalism. We know, for example, that only an estimated 20% of all learning achieved and relevant to the jobs that professionals and individuals do in social care occurs in formal educational and training settings. This leaves approximately 80% of learning occurring in more informal ways (Eraut, 2006). These informal learning opportunities are in the majority work-based, largely unmonitored and not fully researched and the role of managers in capitalizing on this is crucial (Bryans and Mavin, 2003).

Any discussion about the leadership and management of learning has to recognize the importance of establishing a positive culture and how the quality of experiences for those working in social care environments is inevitably connected to learning, continuous professional development and effective change management. For example, addressing discrimination and promoting equality and diversity in workforce development is one important area within change management where solutions might not be clear-cut but have to be strongly connected to policy objectives and strategic actions. Attention to the pros and cons of the repertoire of diversity promotion strategies using learning and organizational development techniques is one step to promoting diversity (Butt, 2006). Secondly, current and future social, political and organizational contexts for practice are leading to significant changes in the employment conditions in social work and social care. These conditions are likely to become more fragmented and simultaneous with the demand to deliver more coherent, consistent and systematic approaches to high-quality services against clearly defined national service outcomes (Fook, 2004; Association of Directors of Social Services, 2005). Taking into account contemporary changes in both children and adult services at the time of writing (Department of Health, 2004a, 2005a) and other areas of the social inclusion agenda, it appears no longer possible to derive a long-term sense of professional identity from working within one particular organizational setting. The structure, and hence the culture, of organizations delivering social care services will inevitably change and evolve on a continuous basis. This raises questions about how we might learn to develop and reframe the essential skills, knowledge and values of social care to meet the demands of an also increasingly regulated and constantly changing environment. This must also be done in a way that suits or can be adaptable to other contexts when necessary. For example within interprofessional relationships and service delivery.

Throughout this text we will be constantly referring to the importance of evidence-based practice and practice wisdom and particularly how these and other forms of knowledge can be managed and utilized in social care. Partnership working is a constantly reiterated theme in public services and any strategy to promote partnerships at the strategic and local level has to recognize active support for learning alongside this.

The study of leadership and leadership development is based, as we will see in the latter part of this chapter, on the idea that public service leaders help to create and realize possibilities for the twenty-first century and that organizational learning and adaptation are part and parcel of any management development strategy (Skills for Care, 2005b). We are not suggesting here that attention to the leadership of learning can be made solely responsible for controlling or monitoring all the details of practice in an organization. If you are an educator, then you will recognize this common expectation from people towards your role in the organization, which carries with it an unspoken assumption that training can offer solutions to many dilemmas in practice. On the contrary, it will be asserted throughout this book that managers and leaders of learning themselves have a specific and integral role in enabling professionals and practitioners to think and act creatively and flexibly so that they can adapt their own abilities and take direct responsibility for developing and improving practice. It is also almost inconceivable to imagine that leadership development can evolve without the active participation of users in leadership and improving the lives of people who use social care services. The promotion of user participation and the role of users in facilitating learning through awareness, reflection drawing upon evidence, partnership working and evaluation is essential. In summary, while this text is aimed at managers and people with specific roles for learning and organizational development, this is a facilitative and partnership process. Predicting change in order to position your organization and the individuals within it to meet potential demands requires everyone to understand and engage in the process of individual as well as institutional learning. We will be drawing attention to the creation of learning opportunities and the use of supervision, appraisal and team work within ‘communities of practice’, while at the same time we will be looking at the more practical aspects of assessing work-based learning and the use of coaching and mentoring techniques.

In conclusion, learning within the organizational context implies approaches that include collaboration, interdependence and independence between those involved inspired by leadership. Before turning to look at how leadership theories can help us in this endeavour, we will first examine the policy context for workforce development in social care and the key principles underpinning these.

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT IN SOCIAL CARE

Social work and social care are a major enterprise in the UK with around £12 billion expenditure and a workforce of over one million (Skills for Care, 2005a). Marsh et al. (2005) go further to state that it also plays a key role in fostering social coherence and represents a major commitment to a socially just society. Yet it is only since the turn of the twenty-first century that any real active scrutiny of who was working in the workforce as a whole, their backgrounds, skills, knowledge and training took place (TOPSS, 2000), resulting in the development of organizations such as Skills for Care (SfC) and the Children’s Workforce Development Council (CWDC) to manage and oversee these strategic developments on behalf of the government. Across health and social care, the government and its employers have been working towards the development of an approach to a workforce strategy that promotes the well-being of users and ensures the best outcomes in their care and support. Irrespective of their employing organization or professional position, staff will need to share a set of competencies so that workforce planning across all services is linked to improving services and allows for progression and transfer of staff as these develop. Finally, a coherent workforce development strategy is needed that it is supportive of the implementation of improved services (Skills for Care, 2005a).

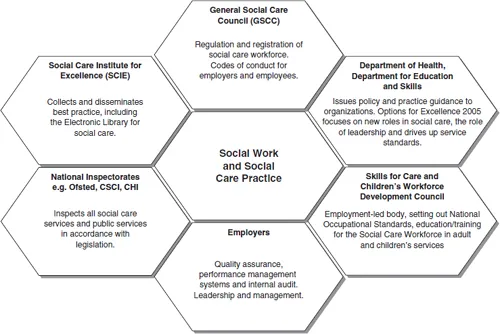

The Modernizing Social Services agenda (Department of Health, 1998) sought to raise the quality of service outcomes through increased regulation and integration of social care services. All service areas have since felt the impact of the government’s agenda and target setting to improve standards in the workforce through increased quality, inspection and regulation. Because attaining higher-quality outcomes for users is related to the better training of those delivering services, a parallel agenda has sought to raise the quality of education and training through more rigorous regulation of the workforce. There have been a number of policy drivers and initiatives since the first National Training Strategy was developed by the Training Organization in Personal Social Services (TOPSS, 2000) to achieve this. Research has documented that 80% of the one million people working in social care, while working face to face with vulnerable people, had no recognized qualifications. The National Training Strategy (Department of Health, 2000) aimed to give a new status to those working in social care which fits the work that they do. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, a network and infrastructure of national stakeholders in workforce development have since combined to support workforce development across the sector and have developed different roles in setting quality standards, for example, through legislation, national service frameworks, a coherent qualifications framework, and the process of regulation, inspection and quality assurance in social care.

Figure 1.1 Key agencies and bodies impacting on learning in social care

Source: Hafford-Letchfield (2006: 44) Reproduced with kind permission from Learning Matters

As established earlier, learning is very much linked to change management and therefore people who understand how to facilitate learning can make an important contribution to the change process. Actively managing learning is also a way of ensuring a balance as well as a match between the needs of professionals with the goals of the employing organization. To achieve this, it is absolutely imperative that there is a close relationship between managers and those involved in learning which is mirrored throughout the organization. To achieve the dramatic step changes as well as the small day-to-day changes to meet the needs for new approaches to services, learning should be understood as more than just as a series of technical processes and issues. It must be supported by a range of other activities, such as supervision, appraisal systems, external and internal training programmes, and the use of reflective learning models, reflective practice and experiential learning are equally important. We will be exploring these more tangible aspects of learning in later chapters of this book.

Paragraph 3 of the GSCC code for employers states:

As a social care employer, you must provide training and development opportunities to enable social care workers to strengthen and develop their skills and knowledge. This includes providing induction, training and development opportunities to help social care workers do their jobs effectively and prepare for new and changing roles and responsibilities. (www.gscc.or.uk/codes_practice.htm)

This responsibility is linked to workforce development planning that is essential for effective organizational learning. The key components of such a plan include:

- A vision for the organization

- How the organization proposes to meet national targets and its own aspirations

- A clarity about access to opportunities which addresses equalities issues

- Definition of training partnership opportunities

- Clarity about the organization’s training priorities in the context of service requirements

- Expectations about the individual learner’s contribution and responsibilities;

- Cost analysis inclusive of indirect or hidden costs

- Support structure for learners

- Underpinning accurate data, both local and national

- How movement towards development through knowledge management, practice/evidence-based training, mentoring and coaching is going to be achieved

- Strategy for investing in training social workers

- Plan for quantifying and meeting practice learning requirements.

(Association of Directors of Social Services, nd: 21)

At the time of writing, some of the most significant achievements in workforce development have been the establishment of induction systems for all new staff and the setting of targets for learning, for example vocational and professional standards, including making social work education based on a degree with a new structure for post-qualifying awards for social work. A number of strategic bodies have been established nationally and regionally which are employer-led in the form of regional planning committees and learning resource centres to take these strategies forward. These aim to facilitate networks between employers, government bodies, commissioners and education and learning providers, and set targets for performance and monitor progress. Improved workforce intelligence and collection of minimum data sets for agencies where social care is provided has meant that there is an acceptance by the sector that it needs to establish and maintain a competent workforce which requires excellence in leadership and management linked to how services should be delivered.

However, the recruitment, retention and ongoing development of the social care workforce continues to be an enormous challenge fraught with difficulties and constrained by inadequate resources to realize this. Improving recruitment into social work, for example, needs a genuine commitment to enhancing the status of the profession, which in turn requires that government policies and public attitudes also reflect an ethical and positive approach to the sections of society with whom social workers engage. McLenachan (2006) points out that this does not always occur in the context of campaigns and policies that marginalize and criminalize those in need of guidance, support and the resources to enable them to lead worthwhile, valued and independent lives. McLenachan cites the changing nature of the workforce as another key factor where discrepancies in pay and status have been highlighted by social workers within interprofessional teams, who feel that ‘the professional status of the social work role is less valued and respected’ (2006: unpaged). Strategies to enhance social work recruitment and retention therefore need to reflect the nature of the settings in which social workers now function and ensure that there is parity between professionals, in terms of pay, status and recognition.

In July 2005, the government announced a review of the social care workforce in England to be led jointly by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) and the Department of Health (DH) to draw together different strands of work in workforce development. The resulting Options for Excellence review (Department of Health and Department for Education and Skills, 2006) made recommendations to increase the supply of all workers within the sector, such as domiciliary care workers, residential care workers, social workers and occupational therapists. It also looked at measures to tackle recruitment and retention issues, improve the quality of social care practice, define the role of social workers (including training and skill requirements), and to develop a vision for the social care workforce in 2020 and a socioeconomic case for improvements and investment in the workforce. Evidence gathered for this report suggested that a continuing high vacancy rate in social care included poor perception of those working in social care and a lack of quality career advice. The highest vacancy rate in social care was found in children’s homes (15.1%) and in care staff in homes for adults with physical disabilities, mental health and learning difficulties (13.2%). Vacancy rates in social care doubles that of all types of industrial, commercial and public services employment, including teaching and nursing, yet demographic trends suggest that demands for social care staff will increase by 25% to meet projections for 2020.

To address these challenges, the government has identified a number of key priorities which will subsequently be addressed in the topics within this text:

- Appropriate support not only...