- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

CBT for Common Trauma Responses

About this book

This is the first book to show how to use cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with the full spectrum of post-traumatic responses; exploring how they affect and relate to one another. Focusing not only on co-morbidity with other anxiety disorders and depression, the book looks more widely at, for example, co-existing pain, substance abuse and head injury.

After discussing how to tailor CBT practice to work most effectively with trauma responses in real-world settings, Michael J Scott goes on to explore the step-by-step treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, other commonly occurring disorders and, finally, secondary traumatisation. Those training to work with young people, or already doing so, will find the focus in Part Three on CBT with traumatized children invaluable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

POST-TRAUMA RESPONSES AND CBT – AN OVERVIEW

Cognitive behaviour therapy has its roots in the ideas of Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher in the first century AD, who said that ‘people are disturbed not so much by things, as by the views which they take of them’ (2011). It is as if people take a ‘photograph’ of the same situation from a different angle, for example people’s differing reactions at a bus stop to the bus being late. But this also applies to extreme situations. Should this ‘late bus’ mount the pavement injuring those standing at the bus stop, in the long term there will be varying responses, including: phobia about travelling by bus, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, etc. In this chapter the typical responses to trauma are described, together with the basics of a cognitive-behavioural approach to clients’ problems.

Adverse reactions to extreme trauma have been noted from antiquity. Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on 2 September 1666 of the beginning of the Great Fire of London and five months later, on 28 February 1667, he wrote ‘it is strange to think how to this very day I cannot sleep a night without great terrors of fire; and this very night I could not sleep until almost 2 in the morning through thoughts of fire’ (Pepys 2003) – he was suffering from.... How did you complete the last sentence? Most commentators make reference to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in connection with Mr Pepys, and indeed this is a possibility. In Mr Pepys’ case, the nightmares may have been taken by yourself and others as representative of PTSD, but in fact the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in DSM IV TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) give equal weighting to other symptoms, such as concentration and connection with others. The diarist was assiduously completing his diaries and socialising, making a PTSD diagnosis unlikely. Mr Pepys probably suffered from a sub-syndromal level of PTSD, but unfortunately he is not around to undergo a thorough diagnostic interview to decide the matter unequivocally and he may in any case have anticipated cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) by writing about his trauma!

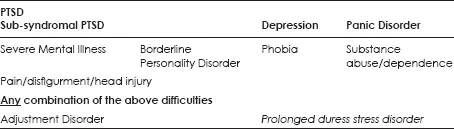

Table 1.1 Common Trauma Responses

Trauma is ubiquitous. Half the adult population (61% of men and 51% of women) experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, with 10% of men and 6% of women reporting four or more types of trauma (Kessler et al. 1995). Despite this, only a significant minority suffer from the disorders shown in Table 1.1 (Kessler et al. 1995). Cognitive behavioural interventions post trauma are based on the tenet that the way in which the trauma and its consequences are appraised plays a pivotal role in whether the person suffers long-term debility (Ehlers and Clark 2000).

The common trauma responses are shown in Table 1.1.

Although PTSD is thought of as the prototypical trauma response, sub-syndromal PTSD is almost as common. In a study of 158 survivors of road traffic accidents (Blanchard and Hickling 1997), 39% developed PTSD and a further 29% developed sub-syndromal PTSD. The disorders in the first two rows of Table 1.1 can develop following a trauma either singly or, more usually, in some combination, for example in the Blanchard and Hickling study (1997), 53% of PTSD sufferers also suffered from depression and 21% with a phobia. A study by Zimmerman et al. (2008) found that 24% of PTSD sufferers were suffering from panic disorder. Many PTSD clients resort to substance abuse as a way of self-medicating (Hien et al. 2010) and this can make it more difficult to treat the underlying PTSD. Fezner et al. (2011) found that childhood trauma, assaultive violence and learning of trauma positively predicted the presence of alcohol use disorders. For those with PTSD, childhood trauma and assaultive violence both predicted alcohol use disorders (Fezner et al. 2011). In DSM IV TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000), a diagnosis of acute stress disorder (ASD) was included and it was thought that the development of this would be predictive of PTSD. However, it has subsequently been found (Bryant et al. 2011) that ASD does not adequately identify most people who develop PTSD and it is therefore not a focus in this volume.

Table 1.1 indicates that the development of severe mental illness (SMI), borderline personality disorder and substance dependence are often linked to trauma. PTSD is common among those with a severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and treatment refractory major depression. A study by Mueser et al. (1998) found that using structured interviews, 42% met criteria for PTSD but a review of the clinical records found that only 2% of the sample carried an assigned diagnosis of PTSD. As such, a significant number of clients with SMI are not recognised and appropriately treated for their trauma-related difficulties. Leaving PTSD unaddressed among individuals with SMI almost certainly exacerbates their illness severity and hinders their care (Resnick et al. 2003). One in four of patients diagnosed with PTSD were also diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and 30% of individuals diagnosed with BPD were also diagnosed with PTSD (Pagura et al. 2010).

Trauma may cause impairment not only directly (primary traumatisation) but also indirectly via pain/disfigurement/head injury (secondary traumatisation), and the latter may then serve to complicate the former. For example, the pain that a person suffers following an accident may serve as a reminder of their accident and exacerbate, say, their PTSD. Thus the pain/disfigurement/head injury of row four in Table 1.1 can make the difficulties cited in the rows above (Table 1.1) more difficult to treat psychologically.

In DSM IV TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000), an adjustment disorder is a diagnosis of last resort and it stipulates that this label should not be used if the client meets diagnostic criteria for any other disorder. It is thus positioned in the bottom row of Table 1.1. Prolonged duress stress disorder (PDSD) is a term coined by Scott and Stradling (1994) to describe clients exhibiting PTSD symptoms but from chronic stressors such as bullying at work or caring for a relative with a progressive neurological disorder. PDSD is not a disorder included in DSM IV TR (it is thus in italics in Table 1.1), and there is a dearth of research on it. It is included by the author in Table 1.1 for its possible clinical value and descriptions of its usage are necessarily somewhat anecdotal.

The focus in this volume is on the CBT treatment of the disorders and combination of disorders in Table 1.1. Some of the responses to trauma in Table 1.1 are a direct consequence of the trauma/s (primary traumatisation), such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, phobia, panic disorder, borderline personality disorder, and psychosis, while others are a response to a consequence of the trauma (secondary traumatisation), e.g. physical injury leading to problems with the management of pain, head injury leading to postconcussive syndrome or cognitive impairment, disfigurement leading to social anxiety. In this volume the treatment of primary traumatisation is dealt with in Parts One and Two, while the focus in Part Four is on secondary traumatisation. In Part Three the focus is on adaptations to treatment for children and those with a severe mental illness.

CBT THEORY AND PRACTICE

One of the core theoretical concepts in CBT is that responses to stimuli are cognitively mediated (see Alford and Beck 1997, and Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Cognitive Mediation

In Figure 1.1 the stimuli might be a hassle, such as the late arrival of a bus. Cognitive mediation theory suggests that it is not this per se that results in an emotional response, say of anger, but cognitions such as ‘this is the second time this week that this has happened’ and perhaps accompanying images of a withering look of disapproval from the boss when I arrive late for work. Because of the perceived injustice, I might push myself vigorously forward (behaviour) as people crowd on to the bus. In turn this might create a further negative stimuli in terms of anger from another would-be passenger as I step on their foot. Thus the chain in Figure 1.1 is actually part of a cycle, which can become a vicious circle if I in turn become angry with my fellow passenger. Cognitive behaviour therapy targets the thoughts, images, emotions and behaviours in Figure 1.1. Whereas cognitive mediation is held to be a necessary part of responding to a stimulus, CBT theory does not claim that cognition is the sole mediator. The stimuli-organism-response model (see Lazarus 2006) was a precursor to the cognitive model and emphasised that the physiology of the individual played a key role in determining an individual’s response to any event. This has been incorporated in CBT conceptualisations of the interactions of physiology, emotions, behaviours and thoughts (see Figure 1.2) (Scott 2009).

The ‘climate’ in Figure 1.2 may consist of events such as hassles or extreme trauma, or the atmosphere in which an individual is ‘breathing’, for example excessive criticism or over-involvement from others, which has been found to be predictive of a relapse in clients with both depression and schizophrenia (see Hooley et al. 1986). For ease of illustration, climate is shown in Figure 1.2 as operating via cognition but it can exert its effects by any of the four ‘ports’ – cognitions, behaviour, emotion or physiology. Each of the four ‘ports’ reciprocally interact with each other. Thus, using the ‘late bus’ example mentioned earlier, if I managed to get on the bus, I might put my ipod on (‘behaviour’ in Figure 1.2), the music might lift my mood (‘emotion’ in Figure 1.2), leading me to feel less tense (‘physiology’ in Figure 1.2), which in turn might lead me to reconsider whether I should bother formally complaining to the bus company (‘cognitions’ in Figure 1.2). However, I may become so engrossed in my music that I miss my bus stop (back to ‘behaviour’ in Figure 1.2) and my new found tranquillity is lost (back to ‘emotion’ Figure 1.2).

In CBT the focus can be on the explicit content of the negative thought to derive more adaptive second thoughts, e.g. ‘True, the bus is late today, but only by five minutes. It is not the end of the world’. However, if ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter One Post-trauma Responses and CBT – An Overview

- Part One Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

- Part Two Principal Disorders other than PTSD

- Part Three Special Populations

- Part Four Secondary Traumatisation

- Appendix A Diagnostic Questions for DSM V PTSD (Proposed Criteria) and Sat Nav

- Appendix B The 7-Minute Interview – Revised

- Appendix C The First Step Questionnaire – Revised

- Appendix D Guided Self-help Post Trauma

- Appendix E Self-instruction for PTSD

- Appendix F Core Case Formulation for PTSD and Sub-syndromal PTSD

- Appendix G PTSD Survival Manual – Revised

- Appendix H Assessment of the Severity of Psychosocial Stressors

- Appendix I Proposed DSM V Criteria for PTSD in Preschool Children and in Adults, Adolescents and Children older than six

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access CBT for Common Trauma Responses by Michael J Scott,SAGE Publications Ltd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.