- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding the Chinese City

About this book

This book teaches us to read the contemporary Chinese city. Li Shiqiao deftly crafts a new theory of the Chinese city and the dynamics of urbanization by:

- exploring the rise of stories of labour, finance and their hierarchies

- examining how the Chinese city has been shaped by the figuration of the writing system

- analyzing the continuing importance of the family and its barriers of protection against real and imagined dangers

- demonstrating how actual structures bring into visual being the networks of safety in personal and family networks.

Understanding the Chinese City elegantly traces a thread between ancient Chinese city formations and current urban organizations, revealing hidden continuities that show how instrumental the past has been in forming the present. Rather than becoming obstacles to change, ancient practices have become effective strategies of adaptation under radically new terms.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding the Chinese City by Li Shiqiao,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia urbana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Abundance

1

Quantity Control

Quantity regulation is spacing regulation; quantity control has a defining role to play in the forms of cities. Characters of cities are, in one important way, quantitative; the densely packed buildings of the urban centres in Hong Kong contrast strongly with the expansive orders of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The ways of life in cities can be deeply influenced by the distributions of quantities. But the distributions of quantities in cities are not easily accounted for, as they seem to result from complex forces compounded together in response to diverse circumstances. Wealth and prosperity determine quantity distributions, as do famine, pestilence, plague, and war; power and privilege formulate their own ranked and hierarchical quantitative scales. The Chinese tendency to control quantities through systems of resident registration (hukou) orders quantities of people in cities in one way, the Western tendency to legislate quantities such as building regulations organizes quantities in cities in another way. Quantities are often ‘out of control’ in cities: migrants, slums, favelas, sprawls, as they trace the demand of the capital which tends to concentrate in cities. However, despite the complexity of quantity distributions, there seem to be consistent strategies that can be articulated; there are quantitative features that are ‘in control’. In this sense, quantity regulation is intellectual; the number of things in cities results from deep philosophical contemplations. Chinese cities, as they respond to various external influences throughout their long history, seem to have maintained a series of numerical schemes that are grounded in intellectual understanding of the natural and human worlds. In conception and substance, these numerical schemes differ from those found in the Western city fundamentally; the Chinese numerical schemes – yin and yang, five elements, twelve temporal markers, sixty-four hexagrams – are often used in combination, which is very different from the notion of a singular numerical order – the One, duality, trinity, dialectics, harmonic proportions – espoused in Western thinking. The material consequences of this difference in cities as buildings take shape in response to these numerical schemes. It is clear that Chinese cities today are heavily influenced by rule-based planning and building regulations, but it is also worth emphasizing that the Chinese numerical schemes have not been displaced; they contribute to the character of Chinese cities as they appear and as they are experienced. Perhaps the most important feature of the Chinese city in relation to quantities is that more is more, and less is less; the moral and aesthetic legitimacy of quantities seems to be distributed across a wide spectrum of numbers, attributing a unique significance to quantities of each order of magnitude. If normative urbanism is managerial in relation to classification, possession, distribution, and movement of quantities, and to mediations between different stakeholders in the city, then this part of the book is about the agreement on quantity regulation before management. It is about the numerical footprints of cultures, and the way in which the city becomes one of the most important material measures of these footprints. Few quantities and their locations are innocent of ideas; they form structured surfaces that impose orders of things onto human and non-human centred entities. To unfold this complex condition under the term of density – still perhaps the most widely used description of quantities in cities – seems to be inadequate, as the notion of density hovers above the orders of things in abstraction.

From Two to Abundance

There seem to be two instincts about quantity. The first is the idea of possessing and displaying more than necessary: abundance. Abundance is important to life promotion and preservation; human communities have always valued the ability to gather resources many times more than is necessary for subsistence. The magnificent displays of resources – contrived through fashions – have been a consistent key to the construction of power and prestige; they have certainly been central to the formulation of social classes. It is clear that the desire for abundance is common to all cultures, and that power and resource distribution in the geopolitical context have always been inextricably linked together to produce a string of empires in history, from the Roman and the Han to the British and the American. These empires may indeed be seen as forced and unequal systems of distribution of resources, brought to reality through geopolitics and war. It should also be clear that cultures impose structured surfaces on the condition of abundance to form different orders of things, through quantity regulation. The same desire for abundance can be subject to different quantity regulation – different orders of things – which will have a decisive influence on how abundance is manifested in cultures, resulting in distinctive urban features.

In the Chinese order of things, abundance seems to be grounded in what may be described as the fertility principle: fertility is the ultimate source of unlimited additional quantities. Perhaps the most stable form of the fertility principle in the Chinese order of things is expressed as a productive binary: the yin and the yang; it is understood as the source for all possible things. This productive binary contains endless variety: the sun and the moon, the male and the female, the hot and the cold, the strong and the delicate, the dense and the sparse, and so on, are all derivatives of the first productive binary. This may appear to be similar to the formulations of duality in Western philosophy, but it differs in two important ways. First, this productive binary in the Chinese cultural context is expressed as a thing-based feature rather than a logic-based definition. Thing-based features cut through many categories that may seem to be illegitimate for Western philosophy to conceive. Second, while duality tends to define an antithetical relationship, pitching one against the other until one is eventually overcome by the other, productive binary assumes a legitimate and mutually dependent existence. The Chinese square word for abundance, feng, is made from symbols of cereal crops and beans; it suggests a strong bond between the meaning of abundance and agriculture. This single Chinese character symbolically unites abundance with agriculture through the fertility principle; the central tenets of Chinese governance never seem to have deviated from the substance of this symbolic union, even when narratives have shifted with time. This, subtly and decisively, formulated many moral and aesthetic frameworks in relation to the quantities of people and things in cities.

Spatial orders, and by implication chance narratives of the future, were established in early Chinese culture in a set of numbers derived from the yin and yang binary: four primary and four secondary directions, with each direction represented by a combination of three lines, or a trigram. A solid line represents the yang and a broken line represents the yin; with two layers of trigrams forming hexagrams, they come to sixty-four different combinations. The use of these sixty-four conditions is not limited to spatial characters; the hexagrams are used to explain almost all events in nature. This is the order outlined in the classic text Book of Changes (Yi Jing). These sixty-four hexagrams are annotated with descriptions that attempt to capture chance meanings in the sequences of yin and yang lines; Carl Jung described these hexagrams and the accompanying notes as ways of thinking through synchronicity (Chinese) rather than through causality (Western), indicating a possible ‘method of exploring the unconscious’.1 Temporal orders are in one way grounded in the four seasons,2 and in another way grounded in five sets of numbers of twelve, popularly marked by twelve animals, representing twelve earthly branches (zhi), totalling sixty in number. The latter scheme has the virtue of marking generational divides, as sets of twelve years. These are used in combination with ten celestial stems (gan) to name each of the sixty temporal markers with two characters. But by far the most extensively referenced numerical scheme has been that of five. The productive binary of yin and yang is overlaid with five elements: metal, wood, water, fire, earth. They form the basis for an understanding of the human body as being made of five vital organs and senses, heaven as consisting of five planets, music as being constructed through a pentatonic scale, food as having five basic flavours, and colour as being made of five essential colours. Each element possesses a double role, simultaneously stronger and weaker than other elements, thus being productive and destructive at the same time: for instance, wood is stronger than earth but weaker than metal; wood is produced by water but produces fire, etc. In various combinations, these numbers influenced almost all material productions in China; from the orientation of buildings on sites to the distribution of wood and earth in buildings, these numerical schemes played decisive roles in traditional constructions.3

John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman thought that, compared with many other societies, the numerical schemes gained ‘unusual currency in China and dominated thinking for an unusually long time’.4 The persistence of these numerical schemes seems to be indicative of a framework of quantity control with deep intellectual roots.5 It is perhaps the underlying fertility principle behind the numerical schemes that gave rise to their lasting and pervasive legitimacy in China. The eleventh-century scholar of the Book of Changes, Shao Yong (1011–77), mused that ‘There is a thing of one thing. There is a thing of ten things. There is a thing of a hundred things. There is a thing of thousand things. There is a thing of ten-thousand things. There is a thing of a million things. There is a thing of a billion things.’6 Each quantity, in this formulation, achieves a unique importance that is commensurate with that quantity; one might be tempted to describe this as numerical empiricism, but it is perhaps more fitting to describe it as a thing-based thought. Taken as such, the traditional Chinese numerical schemes may be seen as ways of understanding the world as being made of things: things can be events and moral principles, objects and subjects, natural processes and human practices.7 ‘Neither God nor Law’ – Marcel Granet admired this Chinese unwillingness to build a transcendental world as ‘resolutely humanist’ in his masterful and sympathetic La Pensée chinoise.8 In this cultural framework, ethics, aesthetics, and governance are not grounded in transcendental worlds, but in the number, nature, and propensity of things.9

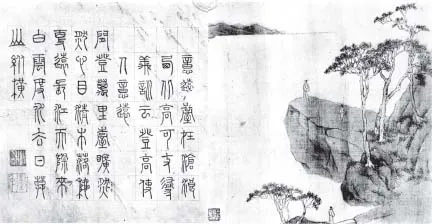

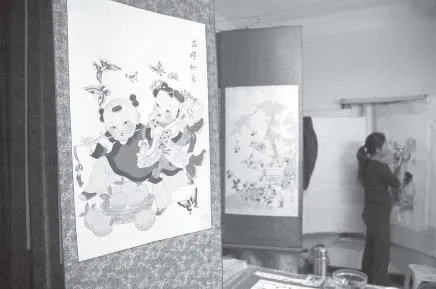

The Chinese quantity regulation has a full spectrum; it ranges from two to abundance. It begins with two as the smallest number (yin and yang), but it has no limit to the largest number, except for the idea of abundance (fengsheng, fanrong) or completeness (quan), which is often judged to be sufficient in relation to specific conditions. Daoists work with small numbers; the Chinese literati tend to be influenced by this tendency to think through the fertility principle with fewer quantities. The paintings of the Ming scholar Wen Zhengming are compelling examples of this end of the spectrum of quantities. In his depictions of the literati garden Zhuozheng Yuan (1531), he used very few things and features to represent the garden as he saw it in the Ming dynasty, as well as the ideal nature as he imagined it. Each of his thirty-one painted scenes reiterates the productive binary in its many aspects: word and image, soft and hard, solid and void, close and far, human and nature (Figure 1.1). These were achieved through an exemplary economy of means in the distribution of things on paper; they are highly valued as literati art. Under the influence of Western art, we tend to discuss Wen Zhengming’s art in terms of abstraction and minimalism, but this is misleading. The carefully controlled display of elements in literati paintings is neither abstract nor minimal; it is figural and sufficient. At the other end of the spectrum of quantity regulation, we can probably use nianhua, or Chinese New Year peasant paintings, as examples of abundance in larger quantities.10 These paintings visualize greater ranges of colours, forms, symbols, and square words (Figure 1.2). Instead of focusing on essential elements, as in the paintings of the literati, nianhua presents a saturated collection of all: abundance in abundant display. The fertility principle is manifested more explicitly through fertility symbols (usually baby boys); their connections with the notion of abundance are immediate and accessible.

Figure 1.1 Terrace of Mental Distance, the Humble Administrator’s Garden (Zhuozheng Yuan), by Wen Zhengming, 1531

Figure 1.2 Peasant painting from Yangliuqing, Tianjin

The Chinese language is filled with expressions of large numbers that indicate the significance of abundance: encyclopaedia is described as a book of 100 subjects (baike), diversity of views as those of 100 families (baijia), antiquity as 1,000 years old (qiangu), and years of longevity as 10,000 years (wanshou). The expression of 10,000 things has acquired a stable meaning for the largest inclusivity (wanwu). Intellectual achievements in this context are not primarily measured through ‘views’ which, despite their ability and promise to amplify amazing details, are often considered to have been derived from one perspective (pi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Theory, Culture & Society

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART 1 Abundance

- PART 2 Prudence

- PART 3 Figuration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index