![]()

PART I

The Nature of Research

![]()

CHAPTER 1

What is Research?

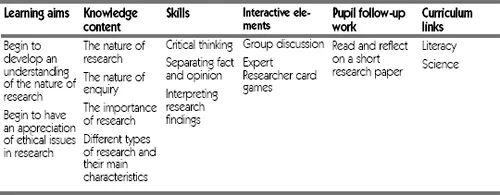

TEACHING CONTENT FOR SESSION 1

Timing: 90 minutes + 30 minutes follow-up work.

The Nature of Research

Research is all around us, indeed, it feels at times as if we cannot escape it! Newspapers are saturated with articles beginning ‘Research findings show …’ and go on to inform us about the UK having the highest number of teenage pregnancies in Europe or that a given percentage of under-12s are obese. Out shopping, we are accosted by ‘researchers’ wanting to know what our preferred brand of shampoo is or whether we think the Prime Minister should step down from office. At school, teachers might ask pupils to ‘research’ the medicinal plants of the rainforest or the religious practices of the Aztecs. On television we are introduced to documentaries that chart the findings of the latest breakthrough in cancer research or the cloning of human embryos. Can all of these be research? If so, what is research?

One way of answering these questions is to explain that ‘research’ is a generic term covering a vast and diverse range of activities. The term is also sometimes used quite loosely to refer to a process of enquiry. One of the characteristics which these activities all have in common is that they seek to ‘find out’. Research is essentially about ‘finding out’ by collecting data. But what distinguishes ‘research’ from a ‘finding-out activity’ is that it also needs to be ethical, sceptical and systematic (Robson, 2002) and, in however small a way, seeks to make a difference. Other finding-out activities may have some, but not all, of these characteristics and may even be unethical – for example, some finding-out activities may be based on criminal activity or rely on deception.

Most pupils, at some point, undertake a school project. Typically this will involve finding out information about a particular topic from books, libraries and the Internet. This is a worthwhile learning experience but a research study, in the sense of our earlier description, goes much further and additionally requires:

- the formulation of a research question and possibly testable hypotheses

- a methodological design

- the collection of raw data

- in-depth analysis

- a scrutiny of validity

- the generation of new knowledge.

Why is Research Important?

It is not unreasonable to question whether we should be undertaking research at all. Some research can be very expensive, so we need to be persuaded that it is an important activity. Some benefits from research are more tangible than others – for example, research that might find a drug to cure multiple sclerosis or slow the onset of Alzheimer’s disease would be universally welcomed. Other kinds of research such as those that investigate our relationship with, and place in, the social world might appear less easy to justify but they are important, too, because they increase our knowledge and understanding. This brings us to a crucial aspect of research which is often overlooked – the generation of new knowledge.

Research is important because:

- its innovative and exploratory character can bring about beneficial change (e.g. cures for debilitating diseases)

- its sceptical enquiry can result in poor or unethical practices being questioned (e.g. corporal punishment in schools)

- its rigorous and systematic nature extends knowledge and promotes problem-solving (e.g. extending our knowledge about different types of nutrition can help promote problem-solving with regard to healthy living).

Research and ‘Truth’

Truth is not an absolute, just as certainty can never be an absolute. We all experience the world in different ways. We have different perspectives and different experiences, and we do not always agree about what is true in those different experiences. So how can we establish ‘truth’ when we are faced with different, and sometimes even conflicting, experiences? Rather than thinking about research in terms of establishing ‘truth’ I prefer to think in terms of research establishing ‘knowledge and understanding’, where ‘truth’ is related to the honesty, rigour and reliability of the approach.

So, what research sets out to do is to establish the ‘truth’ of something through a systematic and rigorous process of critical enquiry where even the most commonplace assumption is not readily accepted until it has been validated. Kerlinger (1986) refers to this sceptical form of enquiry as checking subjective belief against objective reality. Furthermore any ‘truth’ established by research also has a self-correcting process at work in the ongoing public scrutiny to which it is subjected (Cohen et al., 2000) and any research inaccuracies will ultimately be discovered and either corrected or discarded. Short of the absolute truth which we have established is not possible, good research comes very close. It uses an approach which combines reasoning and experience and has built-in mechanisms to protect against error, bias and subjectivity. Borg (1963) regarded research as the most successful approach to the discovery of truth.

Research and Ethics

We will be examining ethics in more detail at various stages later in the book but it is important to introduce the concept of ethics at the outset as this is an essential element of the research process. Research activity has to be ethical, to have regard for the interests and needs of participants involved and also those upon whom the findings of research might have an impact. Research must not cause harm or distress to any individual. When doing research we have to be frank, open and critical about what, how and why our research is taking place. Researchers have a duty to make observations accurately and clearly, whether or not such observations agree with their hypotheses or any previous assumptions. Therefore, researchers do not just ‘make an observation’ or ‘take a measurement’, they must also describe the circumstances in which that observation or measurement is made and who is making it. Researchers expect their methods as well as their findings to be open to public scrutiny. This concern to be systematic, sceptical and ethical is what distinguishes empirical research from other types of finding out activity such as that undertaken by barristers or journalists where investigative findings are used to advocate a particular view, creating evidence and argument to support that view rather than engaging in any doubt or looking for any evidence that might challenge that view. This does not mean that the view is necessarily false but it may mean that individuals such as barristers or journalists fail to acknowledge when it might be.

BOX 1.1 KEY RESEARCH TERMS FOR SESSION 1

data: information (which can be numerical or descriptive) which are analysed and used as the basis for making decisions in research. Data is plural, the singular form is datum but it is unusual to only ever have one piece of information in research so the word datum rarely appears in research writing.

ethical: making sure that the well-being, interests and concerns of those involved in research are looked after. It is imperative that research does not cause harm or distress to any of the participants at any time. These days research is generally expected to follow a code of ethics laid down by an authoritative body.

sceptical: being prepared to question or doubt the nature of findings – even the most commonplace. The process of doubting is an important stage in research if we are to acquire relative certainty (we can never have absolute certainty). So, a sceptical approach tries to find things out but also looks for counter arguments which might reject as well as confirm the findings. Furthermore, researchers allow their findings to be scrutinised by other people and expect them to try and disprove the findings.

systematic: researchers think about what they are going to do and how and why they are doing it in a methodical, purposeful, step-by-step way. Everything is set out very explicitly, e.g. if a researcher is going to ‘find out’ by observation then exactly what is to be observed, who is doing the observing, how, where, in what circumstances and for how long, has to be made clear.

Core Activity

This activity can be done either as a discussion group or as a written exercise (or both) and suggestions for differentiation are given. It appears in a convenient photocopiable format (Photocopiable Resource 1) at the end of the book.

Intermediate level

The core activity draws together the main teaching threads of Session 1 by addressing a frequently posed question about the difference between a researcher and a journalist. Both researchers and journalists engage in finding out activities but as has been explained earlier, one of the principal differences is the sceptical nature of empirical research compared to journalism. A journalist’s report will have a theme or angle and data are often selected to fit this theme, commonly either ignoring, or failing to search for, any data which might disconfirm this theme or angle. Good research might begin by posing a similar question to a journalist but has to be open-minded to possible findings and not only examines the data from a variety of perspectives but also analyses the circumstances in which the data are collected because this could have an important bearing on the findings.

Pupils read the following report (fictionally constructed for the purpose of this activity) and consider whether it is ‘valid research’. Some think prompts are given.

UK fast-food diet producing ‘fat’ babies

New statistics out this month suggest that our obsession with fast food is now producing fat babies. This year a record number of babies – 103 – have weighed in at more than 12lb 12 oz. According to figures from the Office for National Statistics, 1.68% of babies weighed more than 10lb this year compared with 1.45% ten years ago. Boy babies weigh an average of 7lb 8oz, a rise of 2oz from 1973. Experts state that babies who are padded with fat all over their bodies – including, in some cases, their skulls – have a greater tendency towards obesity. In Japan where fast food is not as popular and the average diet includes an abundance of raw fish the average birth weight is 6lb 10oz and in India the average birth weight is less than 6lb.

- Is this report ‘research’?

- Would you describe it as systematic, sceptical and ethical?

- What other information would researchers need before they could draw the same conclusions as this journalist?

- How differently do you think a research report might be constructed?

Guided comment

There are several reasons why a report like this should not be regarded as valid research. Yes, some genuine data are being cited (from the Office for National Statistics) but only selected pieces of data are being used so it is not a systematic approach. It is not sceptical because it does not also look for data that might disconfirm the claim it is making. Moreover, the style of reporting is unethical because it suggests a link between heavier babies and bad...