![]()

1 Location and Movement

1.1 CENTRALITY

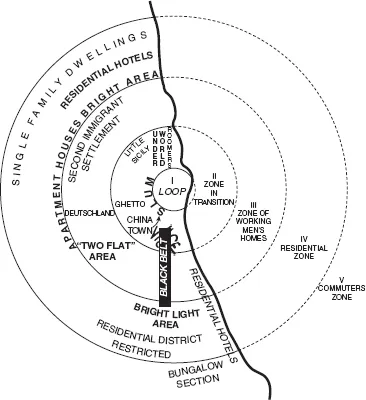

Centrality has always been a concept that has fascinated urban geographers. Just as metropolitan city-regions developed in the post-war period in ways unrecognisable from the early industrial city, so urban geography developed as a discipline (Wheeler, 2005). The arrival of the early mainframe computers in the 1960s gave birth to the ‘science’ of spatial analysis, where the powerful statistical tools afforded by the new technology saw a growing passion for quantifying everything about urban life – demographic trends, migration movements, housing markets, journey-to-work trips and so on (Barnes, 2003). In its earliest manifestations, such as the Central Place Theory of Walter Christaller, or the concentric-zonal, sectoral and multiple nuclei models of Ernest Burgess, Homer Hoyt and Harris and Ullman respectively, who each argued that cities had a discernible internal structure, (see figures 1.1.2 and 3.1.1) usually based upon access to markets and a tendency for activities to cluster in central places.

The power of most cities has tended to emerge due to locational advantage of some sort. From the simplest forms of exchange, when peasant farmers literally brought their produce from the fields into the densest point of interaction – giving us market towns – the significance of central places to surrounding territories began to be asserted. As cities grew in complexity, the major civic institutions, from seats of government to religious buildings, would also come to dominate these points of convergence. Large central squares or open spaces reflected the importance of collective gatherings in city life, such as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the Zócalo in Mexico City, the Piazza Navona in Rome and Trafalgar Square in London. These manifestations of bustling centrality appeared to obey a gravitational pull. In certain extreme cases, such as Madrid and Brasilia, new capital cities were located at the central point of national territory for the most rational form of centralised governance. However, these examples suggest that urban structure was more often than not a process driven by social class and governmental power (especially in colonial cities, where ‘enlightened’ town planning created monumental squares, grandiose government buildings and wide boulevards) than by strict commercial criteria.

Nonetheless, for most modern cities the exemplar of centrality is its central business district. As the likes of Fogelson (2001) have described, American ‘downtowns’ have always been highly contested spaces, given the land values associated with being at the centre of transactional density (transport hubs, retail markets, office buildings, theatres, etc.). Groups of landowners began to tussle over building heights, subways and streetcars from the earliest periods of the modern city. Business groups have long been aware of the reduced transaction costs involved in concentrating business activities, most notably the minimisation of travel time when moving between clients. By the late nineteenth century, technological change had hastened the development of skyscrapers in business districts, much to the chagrin of those sections of the middle classes whose views were obscured by the new high-rises, as well as existing landowners whose property values were undermined by the sudden onslaught of new built space.

Figure 1.1 ‘Downtown Chicago has been a laboratory for urban geographers’

The cause of such conflicts has a simple economic logic:

All functions occupying space within the CBD have in common the need for centrality and their ability to purchase accessible locations. Within the CBD there are diversities which are revealed by the distinctive functional districts and by the individual locational qualities of specific functions … The retail trade quarter is often referred to as the node and is usually on the most central space; the office quarter is well-marked and may have subsections such as financial or legal districts. Besides these horizontal divisions, there are distinctive vertical variations in the distribution of functions; the ground-floors of multi-storey buildings are occupied by activities with the greatest centrality needs. (Herbert, 1972: 90)

However, with increased dispersal and stretching out of economic relations, renting or owning an office or shop in the historically central location began to decline in importance. The question of ‘central to what’ became more important. In the 1930s and 1940s United States, for example, inner areas became challenged by suburban business districts, made possible by ‘streetcar suburbs’ and a burgeoning mortgage industry. The sight of boarded up shops and theatres became commonplace and a growing fear of downtown became internalised within social discourse. As Robert Beauregard argues in his important book Voices of Decline (1993):

The city is used rhetorically to frame the precariousness of existence in a modern world, with urban decline serving as a symbolic coverfor more wide-ranging fears and anxieties. In this role, urban decline discursively precedes the city’s deteriorating conditions and its bleak future. The genesis of the discourse is not the entrenchment of poverty, the spreading of blight, the fiscal weakness of city governments, and the ghettoization of African-Americans, but society’s deepening contradictions. To this extent, the discourse functions to site decline in the cities. It provides a spatial fix for our more generalized insecurities and complaints, thereby minimizing their evolution into a more radical critique of American society. (Beauregard, 1993: 6)

The iconic case is probably that of Times Square, in the heart of Manhattan, which has acted as a barometer of American attitudes towards urban decline and inner city living (Reichl, 1999; Sagalyn, 2001). Thus, central business districts are crucial attributes in the governance of territory, and agglomeration, creativity and control are key themes in understanding the significance of centrality in the contemporary metropolis.

However, commentators are now increasingly thinking through models of growth that reflect a sharply changing set of metropolitan dynamics. Journalistic forays into these new landscapes revealed some fascinating stories. Garreau’s popular Edge City: Life on the New Frontier (1991), collected a series of anecdotal accounts of social aspiration, fear of crime, complex family commuting patterns and dislike for ‘tax and spend’ local government. Joel Kotkin’s The New Geography (2001) told a similar story a decade later, in the aftermath of the dot.com boom that did so much to reshape workplace and living patterns for high-tech employees. Urban theorists have not always been so interested in these landscapes, although Soja’s (2000) Postmetropolis attempts to pull together patterns of deconcentration and recentralisation. This disrupts the conventional image of the city: as Soja (2000: 242) continues, ‘the densest urban cores in places like New York are becoming much less dense, while the low-rise almost suburban-looking cores in places like Los Angeles are reaching urban densities equal to Manhattan’. These fragmented, decentred cities pose numerous problems for analysts. One major issue is that of definition: the following terms all connote differing versions and visions of post-metropolitan life: suburbia; cyburbia; edge city; autopia; non-place. Each implies a shift away from classical or even modern conceptions of the city, symbolised by the cathedral and the city square.

These metropolitian landscapes reflect the importance of speed to the constitution of city life (Hubbard and Lilley, 2004). The arrival of highspeed inner-city motorways and freeways has been a dominant feature of post-war urbanism, shifting residents’ perceptions of the city. This often resulted in the displacement of long-established – and usually working class – communities, as in Berman’s (1982) poignant recollection of the destruction of his childhood beneath the path of the Cross-Bronx Expressway in 1950s New York. Thus, the rhythmic nature of urban public space is important, not least in terms of how the needs of various users drawn to central places are resolved, planned for and regulated. The reclamation of human-scale streetscapes as a focus of collective memory in the urban arena has been an important trend (Hebbert, 2005). However, for the vast majority of cities, be it Beijing, Buenos Aires or Glasgow, the historic core remains a ‘niche’ within a broader city-region economy, with its specialised urban functions such as government offices, department stores, opera houses etc.

This has had an epistemological dimension too, challenging the often taken for granted notion of the ‘city’ as a coherent whole. For Amin and Thrift (2002: 8):

The city’s boundaries have become far too permeable and stretched, both geographically and socially, for it to be theorized as a whole. The city has no completeness, no centre, no fixed parts. Instead, it is an amalgam of often disjointed processes and social heterogeneity, a place of near and far connections, a concatenation of rhythms; always edging in new directions.

This ‘anything goes’ approach is exciting, but threatens to rattle itself to pieces if taken too far.

The return to the centre: revalorising the ‘zone-in-transition’

As described in the entry on global cities, major CBD office districts have become paramount in servicing the global economy. For Saskia Sassen:

At the global level, a key dynamic explaining the place of major cities in the world economy is that they concentrate the infrastructure and the servicing that produced a capability for global control. The latter is essential if geographic dispersal of economic activity – whether factories, offices, or financial markets – is to take place under continued concentration of ownership and profit appropriation. (Sassen, 1995: 63)

Such concentrations have placed huge pressures on the existing urban fabric. This is particularly marked in cities with architecturally or physically distinguished cores. It is impossible to generalise about this. Cities as diverse as London, Barcelona and Rome have each retained vibrant central cities for a number of reasons (e.g., Herzog, 2006).

However, a key theme of locational theory was that of the ‘zone-in-transition’, a term coined by Ernest Burgess in his concentric ring model (see diagram). This term

applies to that part of the central city which is contiguous with the CBD, is characterised by ageing structures and derives many of its features from the fact that it has served as a buffer zone between the CBD and the more stable residential districts of the city. (Herbert, 1972: 105)

Once dismissed as zones of small industry, poor quality environments and inferior accessibility, such areas have become highly sought after or ‘revalorised’ in the post-industrial city. A fundamental aspect of the revival of downtowns was their re-use as a residential neighbourhood, as social groups of varying degrees of affluence populated central cities. A key part of this rediscovery of downtown is the growing demand for inner-city residences, charted by theorists of gentrification (e.g., Ley, 1996; Smith, 1996). Allen (2007), reporting on research carried out in Manchester, England, identifies three principal groups that have (re)colonised these areas for different reasons. First, there are the ‘counter-cultural’ users, often associated with the city’s nightlife. On the one hand, there is a ‘creative class’ of fashion designers, artists and architects; on the other, there is the gay and lesbian community, who have often carved out ‘gay villages’ in neglected corners of the city. Second, there are the ‘successful agers’, those who had raised families in suburbs and who had moved back to the downtown to enjoy its cultural facilities of restaurants and the arts. Third, there are ‘city-centre tourists’, those with a short-term aim of living in cities to enjoy the experience, but with a longer goal of moving to the suburbs. Each of these groups has different levels of cultural skill or capital, social networks and hobbies, and housing histories. But what united them was an interest in the city as a playground, a resource to be enjoyed. As Slater (2006: 738) argues, this has been mirrored in a shift in the focus of gentrification research: ‘The perception [of gentrification] is no longer about rent increases, landlord harassment and working-class displacement, but rather street-level spectacles, trendy bars and cafes, iPods, social diversity and funky clothing outlets’.

Figure 1.1.2 Burgess’ Model of Centrality

The economic recovery of central business districts has led to some critics arguing that city centres are now dominated by suburban ‘family’ values. The density of city life and the vibrant socialities it affords retains a powerful hold over planners and policy-makers. Jane Jacobs’ 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, with its famous Manhattan-based ‘sidewalk ballet’ of dense sociality and pedestrian based ‘street life’, has influenced generations of well-meaning place-makers. It is ironic, then, that critics are now debating The Suburbanization of New York (2007), a collection of polemical essays about the future of what the editors claim to be ‘the quintessential city: culturally, ethnically, and economically mixed, exciting and chaotic, elusive and spontaneous, sophisticated and endlessly creative’ (Hammett and Hammett, 2007: 19). This city is seen to be under attack, a battery of writers asserted, by a combination of gentrification, in-town shopping malls, franchised national chain retail, festival marketplaces and Starbucks (M.D. Smith, 1996). Urban theory is notorious for being built upon a few unique cases and it is prudent to be cautious about the replicability of New York’s experience. But many of the ideas raised above – of elite power in the centre, of the revitalisation, rejuvenation, renaissance of cities, of demographic ‘invasions’ by different social groups – can be traced out in slightly different forms in cities around the world during the 1980s and 1990s.

As noted, the revival of downtowns as a residential environment was driven by ‘counter-cultural’ or ‘bohemian’ social groups (Zukin, 1995). In cities such as New York, artists had gradually been rediscovering the warehouses and lofts of the industrial inner-city, drawn by cheap rents and raw, flexible industrial-sized floorplates. These partially remade city centres became more attractive to white collar workers, and – along with interventionist policing – downtowns became gentrified. This was given an academic rationale with the publication of Richard Florida’s (2002) book The Rise of the Creative Class which became a near-instant hit with policy-makers internationally, welcoming of the message that successful regional economies had large numbers of bohemians, or ‘artistically creative people’ (p. 333), such as artists, designers or musicians. Increasingly, cities around the world have bought into the heavily marketed creative cities policy formula, consciously branding themselves as buzzing, creative metropoles (Rantisi and Leslie, 2006). Reinvestment in the built environment is a key issue here. Conservation, anti-congestion measures and a reaction to modernist comprehensive redevelopment have reinforced and preserved the desirability and quality of life in old city centres (While, 2006). This has met with some criticism, however. On the one hand, the speed of transfer of this policy message has been attacked for its unrealistic assumptions (Pec...