![]()

1

The ageing world

Sheila Peace, Freya Dittmann-Kohli, Gerben J Westerhof and John Bond

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two centuries a gradual transformation has taken place across the world; the population has been ageing due to the on-going decline in fertility coupled with increasing longevity. This global phenomenon will continue to dominate the twenty-first century even though different world regions will experience demographic change at different rates. It is predicted that in the developed regions of the world, including Europe, a third of the population will be aged 60 years or over by 2050; while in the less developed regions the older population will make up almost 20% (United Nations, 2002). These changes also mask dramatic differences. The developed world will have gradually moved to this position supported by relative socio-economic advantage, while within less developed regions the ageing population will have evolved at a faster rate and within a far less well developed infrastructure. This is not a recent discovery; the Population Division of the United Nations has reported on this trend over the past 50 years (United Nations, 1956; United Nations, 1999) identifying the important need for recognition in language which states that population ageing is ‘unprecedented’, ‘pervasive’, ‘profound’ and ‘enduring’ (United Nations, 2002, p. xxviii). Gradually the number of older people will exceed the number of younger people, and amongst the older population there will be an increase in the oldest old. These changes will impact upon all aspects of human life – from family composition, living arrangements and social support to economic activity, employment rates and social security – and to transfers between the generations. While the ageing of the population will be unique within every country and characterised by specific cultural experiences where older people will occupy particular roles as leaders, experts, grandparents; the global nature of ageing will also lead to some common experiences that are characterised because of the years lived.

AGEING IN EUROPE

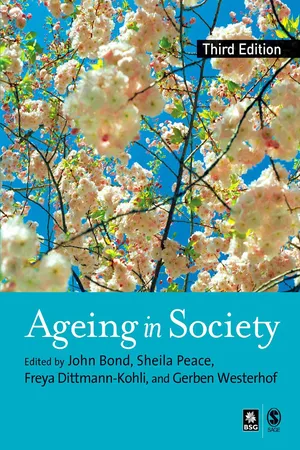

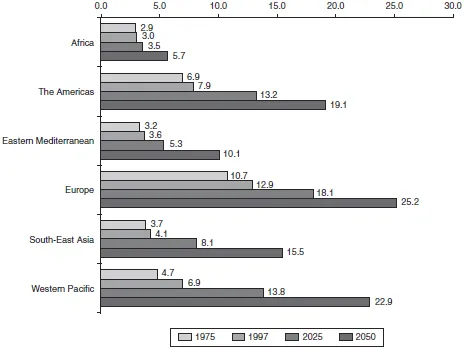

The ageing world reflects the balance between declining fertility and increasing longevity, but as can be seen from Figures 1.1 and 1.2, the balance varies between different parts of the world leading to very different profiles. Dramatically, the figures indicate both the length of time in which European countries have experienced population ageing but also how this continent sits alongside Western Pacific nations in terms of the increase in life expectancy, with the Americas not very far behind. During the second half of the twentieth century, countries represented by the European Union have witnessed not only a decline in fertility – with particularly stark declines in Greece, Spain, Ireland, Poland and Portugal between 1980 and 2000 (OPOCE, 2002) – but perhaps more importantly an increasing life expectancy reflecting improvements in the lives of many Europeans throughout the twentieth century. These trends affect not only the proportion of those living over 65 years of age but more especially the number of the oldest old aged 80 years and over. Indeed, apart from Japan, the EU countries currently have the most pronounced trend in terms of population ageing and this pattern varies between countries. It is expected that by 2015 the average age will have reached 50 years in parts of eastern Germany, northern Spain, central France and northern Italy (Walker, 1999a), and it is estimated that, by 2050, 29.9% of the European population will be over the age of 65, with the proportion of the oldest old (aged 80 years or more) by this time being greatest in Italy (14.1%), Germany (13.6%) and Spain (12.8%) (Eurostat News Release, 2005). However, there is always variation within overall trends and in comparing data across Europe we can see that in some eastern Mediterranean countries the population is ageing at a slightly slower rate (OPOCE, 2002).

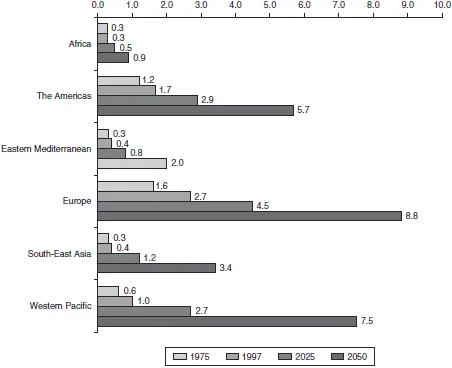

Worldwide data show that the majority of older people are women as life expectancy continues to be higher for women than men. In 2000 there were 63 million more women than men aged 60 or older, and this increase was greater within older age groups (see Figure 1.3). This imbalance between the genders in later life is seen throughout Europe.

Figure 1.1 Proportion of people aged above 65, (percentage of total population)

Source: WHO World Atlas of Ageing (1998) p. 25

Figure 1.2 Proportion of people aged above 80 (percentage of total population)

Source: WHO World Atlas of Ageing (1998) p. 28

Figure 1.3 Proportion of women among people aged 40–59, 60+, 80+ and 100+ years, world.

Source: (United Nations, 2002 p. xxx)

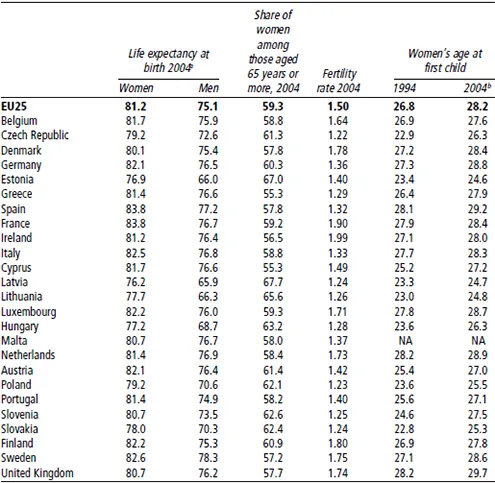

The higher life expectancy of women is particularly prominent within the 25 nations of the European Union where women live on average 6 years longer than men (81.2 years for women compared with 75.1 years for men). As a result of this greater life expectancy, in 2004 women made up 59% of those aged 65 years or more and, as seen in Table 1.1, Latvia had the highest number of women in this age group (68%) and Greece and Cyprus the lowest (55% each).

Given these changes in demography, it is not surprising that Europe is witnessing a projected growth in the old-age dependency ratio (the population aged 65 years and more who are economically inactive as a percentage of the population aged between 15 and 64 who are part of the working population). The ratio rose from 24.9% in 2004 to 52.8% in 2050 for the 25 countries in the European Union (see also Chapter 6).

These statistics provide a brief overview of current demographic trends, but they provide little background to the context in which this population is ageing – people who form different cohorts and different generations. To provide this backcloth first we need to establish the parameters for defining Europe and its characteristics.

IDENTIFYING EUROPE

The context and changing nature of Europe can be defined in many ways. Here, attention is given to the natural and material environment; to the cultural mix; to the political boundaries, reflecting some of the tensions that exist between historical conflict and economic development; and finally to unification and diversity.

Table 1.1 Percentage of women among those 65 years or more in 2004.

Some of the data are estimations.

NA: Data not available.

a2003: EU25, Belgium, Estonia, Italy, Malta, United Kingdom.

b1997: Belgium, 2002: Estonia, Greece, Spain.

Source: Eurostat News Release (2006).

Natural and material Europe

The great Eurasian land mass has commonly been defined as stretching from the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Scandinavian peninsula to the Atlantic Ocean in the west where the North Sea provides the link to the United Kingdom and Eire, to the Mediterranean Sea and Strait of Gibraltar which separate southern European countries from the African continent, and on to the eastern markers of the Urals, the Ural River and the Caspian Sea which have conventionally separated Europe from Asia. This is a continent of great diversity in terms of climate, the dominance of the Alpine mountain chain, and the human development of fertile plains alongside its central river systems from the Volga to the Danube to the Rhine to the Thames.

It can be seen geographically as up to fifty countries that can be divided into a number of regions – eastern Europe, south-east Europe, central Europe, southern Europe, western Europe, Scandinavia and the British Isles/UK – ranging across a vast mix of rural and urban landscapes. There are 18 cities having populations exceeding one million inhabitants, and areas of dense population are seen in contrast to the rural hinterland of the northern continent (Eurostat News Release, 2004). Already the variation in rural and urban living can lead to lifestyles that can be described as more peasant-like or more metropolitan while at the same time there are also cultural stereotypes attached to regions known as Mediterranean, Scandinavian or Alpine. Given this breadth, is there a European culture?

Cultural Europe

Diversity is a central part of European culture. History has shown that it has been the scene of kingdoms and empires that have moved through periods of conflict and stability to create more cohesive nation states. Whilst the Greek and the Roman civilisations have influenced and underpinned the development of cultural traditions through language, literature and political processes and structures, adoption of the Christian religion has also been central both to periods of conflict and the regional adoption of particular religious ideologies. Whilst Roman Catholicism is the chief religion of southern and western European countries, Protestantism is dominant in the UK, Scandinavian countries and parts of northern Europe. But these are not the only orthodoxies; the Orthodox Eastern Church predominates in eastern and south-eastern Europe, and the Muslim faith is central to parts of the Balkan Peninsula and Transcaucasia. Indeed, whereas certain religions may be dominant in particular areas, migration has also led to the spread of a variety of religious groups especially within urban and metropolitan centres.

Across Europe national identities may commonly involve particular religious traditions, but the impact of recent political history also nurtures aspects of identity formation, and politics and religion are often intertwined. During the twentieth century, Europe not only witnessed two world wars but also saw the rise and demise of two ideological blocs, for and against communism, in what was known as the ‘cold war’. Here opposition was seen between western European countries influenced by the USA in opposition to communist countries of eastern Europe dominated by the USSR. In more recent times the breaking-up of the Soviet bloc in the early 1990s led to both the democratisation of former communist countries and to ethnic nationalism within the region of the former Yugoslavia. Consequently, a number of countries have been transformed from states with centralised economies towards more market-based economies – countries such as Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia, where the suppressed national cultures are now becoming more visible.

Stability, continuity and change are key factors when defining the context of Europe. International migration has been a dominant experience across the continent for a number of centuries. People have moved not only between countries but also between continents. For different nations this can be seen as part of both an historic colonial past and a recent past; whilst for individuals and groups emigration may have been prompted by the desire for asylum, employment and an improved quality of life. Such experience gives the European continent a very different historical and cultural profile from that of younger continents.

Migration patterns are also subject to on-going development influenced by political, economic and demographic trends. Warnes et al. (2004, p. 311), commenting on the European experience, says:

Only in the last half-century has the net movement reversed, and since the 1980s another radical change has occurred: Greece, southern Italy, Spain and Portugal, which through most of the twentieth century were regions of rural depopulation and emigration to northern Europe, the Americas and Australia, have become regions of return migration and of immigration from eastern Europe and other continents (Fonseca et al., 2002; King, 2002).

So, in contrast to the national unity of the states in North America, cultural diversity both within and between countries in Europe is historic and on-going. Nevertheless, political unity between many European countries has been seen by some as an advantage and a strength.

Political boundaries

A period of conflict from the late nineteenth century through to the mid twentieth century brought a number of western European political leaders to consider that stability and peace could be secured only through developing economic and political unity. This led to the setting up of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 with six members – Belgium, West Germany, Luxembourg, France, Italy and the Netherlands. The success of the ECSC led them to sign the Treaties of Rome in 1957 establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) and the European Economic Community (EEC) through which they removed trade barriers between them and formed a ‘common market’. In 1967 these three institutions merged into a single Commission establishing the European Parliament, leading to direct elections for members from each country in 1979 (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 The development of the European Union

European Commission (EC) 1967

- The EC was formed from a merger of the European Economic Community (Common Market); the European Coal and Steel Community, and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM).

- Denmark, Ireland and UK join in 1973; Greece joins in 1981; Spain, Portugal join in 1986.

Treaty of Maastricht, 1992 creates the European Union, 1 November 1993

- Belgium (EUR), Denmark, France (EUR), Germany (EUR), Greece (EUR), Ireland (EUR), Italy (EUR), Luxembourg (EUR) the Netherlands (EUR), Portugal (EUR), Spain (EUR), United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

1 January 1995

- Austria (EUR), Finland (EUR) and Sweden join in 1995.

- Turkey is considered as a candidate country in 1999.

Treaty of Nice, 2003, establishes new rules governing size and ways of working for EU institutions.

1 May 2004

- Ten new countries join the EU to become the EU-25.

- Cyprus (Greek part), Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia.

- Croatia is accepted as a candidate country in 2004.

- Bulgaria and Romania to join the EU in 2007.

(EUR) Countries currently adopting the European currency

Source: Europa (2006)

New forms of co-operation concerning defence and inter-governmental cooperation between member states were introduced through the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992, leading to the creation of the European Union (EU). In 1993, 12 nation states were united – growing to 15 in 1995 – and the development of economic and political integration has led to a wide range of common policies from agriculture to consumer affairs, from energy to transport, each leading to ongoing debate concerning ...