- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A thorough and wide-ranging synthetic account of social scientific research on consumption which will set the standard for the second generation of textbooks on cultures of consumption."

- Alan Warde, University of Manchester

"The multi-disciplinary nature of the book provides new and revealing insights, and Sassatelli conveys brilliantly the heterogeneity and ambivalent nature of consumer identities, consumer practices and consumer cultures... Newcomers to consumer culture will find this an invaluable primer and introducton to the major concepts and ideas, while those familiar with the field will find Sassatelli?s sharp analysis and discussion both refreshing and inspiring."

- James Skinner, Journal of Sociology

"This is a model of what a text book ought to be. Over the past decade the original debates about consumption have been overlaid by a vast amount of detailed research, and it seems unimaginable that a single text couuld do justice to all of these. To do so would involve as much a commitment to depth as to breadth. I was quite astonished at how well Sassatelli succeeds in balancing the two... Ultimately, it?s the book that I would trust to help people digest what we now have discovered about consumption and start from a much more mature and reflective foundation to consider what more we might yet do."

- Daniel Miller, Material World

- Alan Warde, University of Manchester

"The multi-disciplinary nature of the book provides new and revealing insights, and Sassatelli conveys brilliantly the heterogeneity and ambivalent nature of consumer identities, consumer practices and consumer cultures... Newcomers to consumer culture will find this an invaluable primer and introducton to the major concepts and ideas, while those familiar with the field will find Sassatelli?s sharp analysis and discussion both refreshing and inspiring."

- James Skinner, Journal of Sociology

"This is a model of what a text book ought to be. Over the past decade the original debates about consumption have been overlaid by a vast amount of detailed research, and it seems unimaginable that a single text couuld do justice to all of these. To do so would involve as much a commitment to depth as to breadth. I was quite astonished at how well Sassatelli succeeds in balancing the two... Ultimately, it?s the book that I would trust to help people digest what we now have discovered about consumption and start from a much more mature and reflective foundation to consider what more we might yet do."

- Daniel Miller, Material World

Showing the cultural and institutional processes that have brought the notion of the ?consumer? to life, this book guides the reader on a comprehensive journey through the history of how we have come to understand ourselves as consumers in a consumer society and reveals the profound ambiguities and ambivalences inherent within. While rooted in sociology, Sassatelli draws on the traditions of history, anthropology, geography and economics to provide:

- a history of the rise of consumer culture around the world

- a richly illustrated analysis of theory from neo-classical economics, to critical theory, to theories of practice and ritual de-commoditization

- a compelling discussion of the politics underlying our consumption practices.

An exemplary introduction to the history and theory of consumer culture, this book provides nuanced answers to some of the most central questions of our time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

THE RISE OF CONSUMER CULTURE

In most conventional descriptions of the birth of capitalism, consumption is rarely portrayed as a crucial phenomenon, let alone one which is capable of being the propulsive force behind historical processes. The birth of modern capitalist society is normally explained through a series of diverse variables, all of them inherent, as it were, to the sphere of production: from the industrial revolution to the spread of an industrious and calculating bourgeois mentality. However, the social sciences have recently begun to recognize that the history of consumption – intended as a bundle of practices, a contested object of moral judgement and a category of analysis – is extremely important in understanding the genesis of the capitalist system as well as its late-modern variant which is strongly characterized by an eye-catching circulation of commodities.

Thus, through changes in consumption we can re-read the history of modernity and of the expansion of Western civilization. By way of example, in Seeds of Change, the historian Henry Hobhouse (1985, xi) writes that ‘The starting point for the European expansion out of the Mediterranean … had nothing to do with, say, religion or the rise of capitalism – but it had a great deal to do with pepper. The Americas were discovered as a by-product in the search for pepper’. Of course, it was not only desires of consumption that stimulated transoceanic crossings, or that these alone brought new possibilities for consumption. Nevertheless, capitalism was induced not only by the industrial revolution which reached its apogee in the second half of the 19th century, or by the calculating mentality of the petite bourgeoisie of the 17th and 18th centuries (perhaps inspired by the ascetic Calvinism which so fascinated Max Weber), but also by consumption, from the extravagances of the nobility and high finance to the small luxuries of the masses. This, as we shall see, happened from the tail-end of the late Medieval period.

According to Weber (1930, orig. 1904–5), the Protestant mentality – especially in its Calvinist form – promoted an ascetic and calculating attitude which favoured capitalist accumulation, forming through frugality and hard work the financial capital necessary for the development of the capitalist enterprise. However, we should also remind ourselves that contrasting with this asceticism was a hedonistic mentality which saw as much meaning in the comforts and even in the waste of consumption. This mentality was chiefly represented by the nobility, high finance and, in ever increasing numbers, by the lower orders. Thus, hedonism and waste existed – and indeed had re-emerged during the Renaissance – alongside asceticism and prudence. In other words, somebody had to consume those goods which were produced through the industriousness of the first capitalists, and they had to have good reasons for doing so.

As I shall show later on, contemporary economic and cultural history demonstrate that it is impossible to provide a sharp divide between a preceding puritan and Protestant era which gave an initial impulse to accumulation, and a subsequent period of hedonism from which the so-called ‘consumer society’ sprang forth (Appadurai 1986a; Brewer and Porter 1993; Campbell 1987; Mukerji 1983). From this perspective, the spread of new models of consumption, spurred on by international commerce, the colonies, courtly excess and an increasingly materialistic mentality, gradually favoured the development of a system of credit and debt, and more generally stimulated competition and cross-fertilization between different social groups, other than mere economic exchange. This was accompanied by the speeding up and expansion of the dynamics of taste, freeing them from the constrictions of the medieval period. In medieval society’s closed and tight social hierarchy, the tastes and dynamics of consumption were also fairly rigid, tending to reproduce the existing social order. The consolidation of modern society and the relative social mobility which characterizes it have instead brought forth (and been favoured by) continuous – and ever more rapid – changes in lifestyles.

The same supply/demand dichotomy which has been so important in the development of economic analysis does not seem to take account of the phenomenon of consumption. Above all, this is because consumption is not only expressed in the demand for goods (the purchase of objects or services) but in their use (their symbolic associations, the ways in which they are distributed within families, the practices and discourses through which they are managed, etc.) which in ordinary life fills goods with value. The notion of demand in some way isolates consumption from the web of social activities (including production) and reduces processes of consumption to a series of disentangled and re-aggregated acts of purchase, thus making the commercial value of an object appear to be a good proxy for its social and cultural value. Instead, I will show that economic value is culturally constructed through deep-seated historical processes. Obviously, there are events which make a difference and particular places and periods in which the clock of the history of consumption seems to tick more quickly: just think of the precipitating role that the Second World War had in spreading and making legitimate American lifestyles across Western European countries. However, to understand what characterizes today’s consumer society, one has to keep in mind a series of phenomena which have developed over a long period at different speeds and in different places. The so-called consumer society is in fact profoundly interconnected with a type of society that sociologists conventionally term ‘modern’ (Lury 1996, 29 ff.; Slater 1997, 24 ff.) and which has a complex historical genesis. Consumer society can thus be associated with the wide diffusion of a variety of commodities (which occurred, of course, in different waves: for example, colonial goods like sugar in the 17th and 18th centuries, fabrics and clothes in the 19th century, cars and domestic technology in the 20th century). Broadly speaking, it is also coterminous with the process of commoditization, so that more and more objects and services are exchanged on the market and are conceived of as commodities. Furthermore, it develops along with the globalization of commodity and cultural flows; with the increasing role of shopping as entertainment and spectacle; with the increasing democratization of fashion; with the growth in sophisticated advertising; with the spread of credit to consumers; with the proliferation of labels defining a variety of consumer pathologies like kleptomania or compulsive buying; with the organization of associations dealing with consumer rights or calling into being the consumer’s political persona … The list could hardly be closed and perhaps what is most important here is to realize that all these phenomena are linked to broad cultural and political principles which are themselves also considered typically modern; these range from the identification of freedom with private choice to the consolidation of impersonality and universalism as recommendable codes of conduct for social relations; from the idea that human needs are infinite and undefined, to the expectation that each individual can (and must) find ‘his/her own way’, as personal as possible. The particular cultural politics of value which underpins the development of ‘consumer society’ is thus not a natural one, it is one which requires a process of learning whereby social actors are practically trained to perform (and enjoy) their roles as consumers.

1 | Capitalism and the Consumer Revolution |

For a long time sociology and history implicitly followed a dualist position which gave the organization of production the role of the engine of history. Studies of 17th to 18th century material culture have discredited this productivist vision which typically presented consumer society as emerging at the beginning of the 20th century as a sudden and mechanical reaction to the industrial revolution, and then gradually penetrating all social classes through the consumption of mass-produced goods. On the basis of the work of the French historian Fernand Braudel (1979), who began to study this problem not as a separate economic phenomenon but as an integral part of culture and the material life of people, historians have begun to give due consideration to the development of material culture, and, in fact, to give it a propulsive role in the historical process. From the 1980s onward the understanding that consumer society is not comprehensible as just a late derivative of capitalism became established; consumption was now seen as having actively participated in the development of the capitalist system.

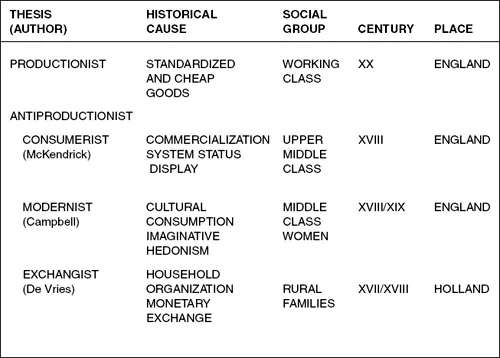

In this chapter we shall consider some of the most important overall explanations for the rise of the consumer society which have replaced the productivist thesis. These anti-productivist views have foregrounded various aspects of consumer culture – from promotional techniques, to hedonistic ethics, to commercial incentives (Campbell 1987; De Vries 1993; McKendrick et al. 1982). I will then insist on the need to adopt a multi-causal approach, considering economic, cultural and social dimensions and abandoning a linear model of development in favour of an understanding of the multiple geographies and temporalities of different consumer patterns and values. Drawing on Werner Sombart’s work on luxury, the consumption of superfluous and refined, colonial and exotic goods, together with the forms of knowledge which accompanied them, are seen as pivotal for a variety of institutions which have worked as engines for the rise of consumer culture, from the court with its competitive merry-go-round of fashions, to the urban environment with its succession of shopping places, to the bourgeois home with its emphasis on decent comfort and polite refinement.

Consumption, production and exchange

As suggested, traditional wisdom has considered consumer culture as the late consequence of the industrial revolution; in this productivist vision the so-called ‘consumer society’ was but an effect of the capitalist mode of production. Industrialization is thus seen as responsible for the spread of large quantities of standardized commodities, made accessible to ever-larger segments of the population. In other words, the industrial revolution, conceived of as a radical transformation of the economic structure of production, was at the root of the revolution in demand. From this point of view, the consumer society can be conceived of as a cultural response which logically follows a more fundamental economic transformation. The consumer society therefore coincides with ‘consumer culture’ or ‘consumerism’. Consumer culture is itself defined in reductive and ambiguous terms, mixing and meshing practices with representations, consumer meanings with advertising images – and indeed reducing the former to the latter, thus reducing consumption to mass culture, which is in turn depicted as a mere derivative of industrial mass production. In this way, even when consumption is the subject of analysis, it is both inappropriately and unwillingly taken back to production.

A first important step towards opposing such a position has been taken by historians. Through the use of a variety of quantitative sources (from business profits and taxes, to wills, etc.) and qualitative data (descriptions of stolen objects in police reports, personal diaries, etiquette guides, etc.) historians are now able to indicate that a growth in material culture in Europe began in the early modern period and, thus, before the industrial revolution (Fairchilds 1998). A clear growth in consumption was registered above all from the second half of the 17th century and throughout the 18th century in many European nations and in different social classes – from the inhabitants of Paris (Roche 1981), to Dutch peasants (De Vries 1975), to the urban as well as rural English (Shammas 1990; Thrisk 1978; Wetherhill 1988). Of course, given the paucity of adequate sources, it is difficult to identify with certainty the pace of the growth of consumption in this period. It is also evident that the early development of modern consumption has its own particular, uneven and partial geography. Even within a given nation it is difficult to talk of an increase in consumption for the whole population, since consumption could vary massively between social classes, whilst gender and generational differences accounted for the unequal distribution of goods within the same family. Nevertheless, from the second half of the 17th century people of every class and gender began to acquire via the market many more finished goods, in particular household furnishings (paintings, ceramics, textiles) and personal ornaments (umbrellas, gloves, buttons) (Borsay 1989). At the same time the diffusion of sugar and new stimulants like tobacco, coffee, tea and cocoa seems to have played an important role in revolutionizing consumption (Mintz 1985; Schivelbusch 1992). One must not forget either the spread of prints as decorations for domestic space, which paralleled the specialization of rooms in the houses of the nascent bourgeoisie (Perrot 1985; Schama 1987).

These examples are not however due to mass production. Up until the 19th century what was available was the result of flexible production in small units, rather than standardized production in large structures typical of the industrial revolution.1 In the same way, even though superfluous commodities were widely available, their distribution was through channels of small specialized retailers (Fawcett 1990). Manufactured goods were often retailed directly by the producers, who offered the possibility of various personalized finishings for the goods. The situation was similar in many European nations, fostered by international commerce and the diffusion of commodities from the colonies.

Figure 1.1 The theses on the birth of the consumer society

Taking stock of the studies of the general growth in consumption in early modernity, authors like Neil McKendrick (1982), Colin Campbell (1987) and Jan De Vries (1975), have led the way to what I call the anti-productivist turn. In fact, not only do their studies push back the revolution in demand to the 18th century or the second half of the 17th century, but they also present alternative theoretical paradigms, providing an anti-productivist view of the birth of consumer society. They all attempt to show that demand, more than production, became a vital part of the economic and cultural process. In different terms, they all underline that it was the desire for consumption more than processes of work that played an active role in giving shape to modernity. Let us consider them one by one, outlining their main arguments (see Figure 1.1).

McKendrick’s observations marked a shift in studies of the history of consumption. McKendrick stresses that the consumer revolution was ‘the necessary analogue to the industrial revolution, the necessary convulsion on the demand side of the equation to match convulsion of the supply side’ (McKendrick 1982, 9). According to this British historian, the revolution in consumption should be placed in the second half of the 18th century in England, and be seen against the background of a society that was becoming more flexible and less hierarchical as a result of the status aspirations of the new bourgeois classes; in McKendrick’s view they saw a possibility for social advancement in the conspicuous emulation of the consumption of the class which had until then been the custodians of refinement – the nobility. Furthermore, the desire of the bourgeoisie to consume was stimulated by avaricious entrepreneurs who, despite not yet using industrial techniques of production, knew very well how to use sophisticated modern sales techniques to foster these status aspirations.

To this end McKendrick mentions Josiah Wedgwood’s porcelain, among the most important of the period and still some of the most appreciated in the world. Wedgwood understood and exploited the pretensions of the nobility and the aspirations of the bourgeoisie, getting his porcelain sponsored by royal families throughout Europe and then benefiting from the aura created by this apparent patronage of the ‘great’ to sell his wares at a high price to the nouveaux riches. This entrepreneur was one of the first to adopt genuine ante litteram marketing techniques (that is, the planning of production with the sale in mind) and design (applying sophisticated aesthetics of artistic merit to consumer goods). All this with the intent to produce a large quantity of goods, available at accessible prices, ready to satisfy the ascendant bourgeoisie’s desire for taste and refinement. As Andrew Wernick (1991) writes, Wedgwood heralded a ‘promotional culture’ in which objects are products commercialized with a particular market in mind. For example, he cultivated the growing interest amongst the privileged in archaeology and antiquity, and exploited it by producing ‘Etruscan’ vases which were exhibited in spectacular fashion in his chain of shops and subsequently achieved even greater prestige through being displayed in the homes of the nobility. From this perspective, the demand for refined goods on the part of the new ascendant middle classes, provoked by shrewd entrepreneurs and artisans, created the market which modern industry needed and soon learned to exploit to its advantage. McKendrick therefore offers us an explanation for the birth of consumer society that I may define as consumerist. In this way the process of industrialization is the effect and not the cause of new desires of consumption, and these corresponded with the possibility of displaying one’s status and were stimulated through promotional techniques.

In sharp contrast to the productivist thesis, McKendrick treats demand as an active part of the historical process which developed capitalism. However, he does not historicize demand itself. On the contrary, he portrays demand as the result of some ‘natural’ human inclination to imitate those with power and status, waiting to free itself the moment material conditions permit. The birth of consumer society is thus credited to consumerism, which in turn, is seen as catalysed by the dynamism of fashion fused with social emulation and encouraged by the manipulative sales techniques of wily producers. Therefore, his explanation is not able to take account of the cultural specificity of a social environment in which it was becoming possible, lawful, and even proper (for some) to follow fashion, to spend for their own pleasure, to be attracted by the exotic, to learn to enjoy luxuries and ostentation, etc. The motives and values which pushed the first bourgeoisie to consume more and more are never taken seriously and given the attention they deserve: instead they are reduced to emulation, envy or the demonstration of status.

In an explicit countering of McKendrick’s thesis, and in particular of his historically and culturally flat view of the motives for consumption, Campbell offers an explanation I may define as modernist. His well-known work The Romantic Ethic and the Sp...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Born to consume

- Structure of the book

- Part I The Rise of Consumer Culture

- Part II Theories of Consumer Agency

- Part III The Politics of Consumption

- Epilogue: Consumers, Consumer Culture(s) and the Practices of Consumption

- Further Reading and Resources

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Consumer Culture by Roberta Sassatelli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.