![]()

PART I

THE GROUP

SUPERVISION

ALLIANCE MODEL

![]()

1

Setting the scene

Dramatis personae

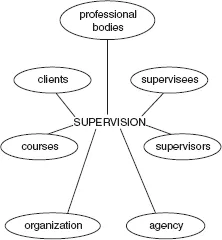

Group supervision is an enactment. For the most part, supervisor and group supervisees are on stage. However, off stage, there are at least two powerfully silent participants, and possibly one or two other influential players who may appear in the opening or closing acts, or at times of crisis.1 In setting the scene, it is worth taking time to consider each character in turn. Figure 1.1 represents these as stakeholders in the supervision.

Figure 1.1 Stakeholders in group supervision

The supervisee

Group supervision is the opportunity for each counsellor, in the role of supervisee, to make use of the reflective space reserved for her. She will not be able to use it for the benefit of her clients, or her own professional development, unless she can come to look forward to supervision as sufficiently safe and challenging. Additionally, it will be a major forum for the development of the 4 Cs – Competence, Confidence, Compassion and Creativity. Traditionally, supervision writing has been concerned with the supervisor – how to do, or improve, supervisor practice. This preoccupation mirrors societal and professional assumptions that ‘the expert’ is hierarchically more important than the ‘learner’, and needs help in becoming yet more expert. Too often, in my opinion, such books can begin to treat supervisees as ‘them’ (rather as some counselling textbooks tend to talk about clients). This can disguise the reality that supervisees are adult learners, most of whom are capable of developing their own ‘internal supervisor’. In order to do so consciously, there may be information that can be spelled out before they ever enter supervision, and skills that they can learn or transfer to this new context.

Presenting clients or professional issues for supervision in an economic and accessible way is a skill in itself. To present in a group requires added courage and self-discipline. Using a group setting for reflecting and learning is also a specific ability. When starting in group supervision, supervisees may need to be reminded about some facts of group life, and encouraged to become aware, ahead of time, of some of the hopes, expectations, apprehensiveness and fears which they may habitually bring to group experiences. Most particularly, they need to be clear that in a group they will be (to greater or lesser extent, depending on the group agreement) not only supervisees but also co-supervisors. As such, they need a good deal of the skill and sensitivity that should be expected from supervisors. So, do supervisees, then, have the information, skill, support and challenge (Egan 1994) needed to enter actively and creatively into this group supervision alliance?

Much of this book is aimed at supervisors, but I hope it will be accessible and useful to group supervisees as well. While reading the case studies, which focus on supervisor practice and perspective, readers should also think about what would be happening for each supervisee in the groups.

The client

The client is one of the two powerful off-stage characters. Working well with the client is the heart of the matter – the counsellor is committed to practising to the best of her ability and the supervisor is employed to promote best work. In group supervision in particular, where the secondary satisfactions or hardships of group work can become centre stage, attention for the clients can be squeezed out. Would this client recognize himself, or the counselling issues being engaged with? Would that client experience group members as working to respect, understand, and help her? Will this supervision really result in helping them become more who they want to be and to act in ways which are resourceful and in their best interests? It will be salutary to think, in this book and during group supervision in practice, of the client’s thoughts and feelings if he were a fly on the wall.

The supervisor

The supervisor is the person responsible for facilitating the counsellor, in role of supervisee, to use supervision well, in the interests of the client. His particular need is to have clarity about the task, so that he can be group manager as well as supervisor in a group. The role of group manager requires skills and abilities distinct from those of supervisor. Many will be transferable from other contexts. Some developed skills need to be left behind. The role entails sub-roles which may be in tension with each other. In addition to a clear map or understanding of the general tasks of supervision and their complexity, a group manager also needs:

- An awareness of his own style, strengths and limitations in leading and facilitating groups. What abilities might he need to develop to do it better? Are his strengths as a supervisor well integrated with his abilities to engage supervisees in each other’s supervision? Is he able to balance the needs of the supervision task with the needs of individuals and the demands of group building, maintenance and repair? The following chapter suggests three types of group supervision leadership, style and contract. The supervisor needs to have made suitable choices with regard to the style of group he intends to lead/offer and to communicate his choice clearly.

- Access to maps of group task and process. The supervisor needs to have some understanding of how groups contribute or detract from the task of supervision and his ability as a supervisor. He will need to have ideas about how individual members and the group as a whole can be helped and hindered by the presence of group forces.2 Cognitive frameworks add to an understanding of group dynamics and processes but, importantly, they also need to help him manage confusing or difficult incidents in the group with increased awareness and trust in physical, sensory based processing. Counselling itself is a more physical activity than we realize. All thinking and feeling is rooted in and mediated by our sensory perception – seeing, hearing, touch, movement, smell and taste. In a one-to-one relationship, we can often process sufficient units of verbal and non-verbal communication in time to identify thinking and feeling – something which ‘makes enough sense’ to us to help us decide what, if anything, to say. A group, however, is almost always too complex in its units and levels of communication for processing minute to minute. A group supervisor, I suggest, has to learn to trust his senses – to think in physical imagery – ‘Who has the reins here?’ ‘Who is out in the cold?’ ‘Where have we got lost?’ ‘This is euphoric – we need to come down to earth.’ ‘I’ve lost the tune and the rhythm.’ ‘I was imagining a full-bodied bowl and suddenly it shattered.’

As we will see later, the amount of group skill required depends on the chosen mode of group. The supervisor needs to ensure that the particular supervision set-up he has chosen is well enough suited to his style and abilities as group facilitator.

The profession, the agency and the training course

Group supervision always takes place within a professional context – and often in the context of an agency, organization or training course. Most counsellors subscribe to a professional alliance which is codified in working agreements about ethics and good practice. The professional associations which represent and monitor this alliance for us are, collectively, another powerful offstage character in the group supervision enactment. Organizational, agency and course managers who are responsible for managing the context of the group are influential characters at the outset. They determine the supervision contract and they may engage with supervisor and/or supervisees at times of crisis or transition.

When one is training supervisors (and perhaps supervisees), it is informative to ask them to do an exercise in which they take different ‘stakeholder’ roles and speak from those perspectives about the supervision process. Any conversation between a supervisor and a person speaking in role for some professional association (for instance BACP or UKCP) instantly reveals what heavy expectations those bodies have of their supervisors and how little supervisors feel supported or even informed by them. When, in addition, someone speaks on behalf of an organizational manager, expectations of the supervisor become greater, and perhaps conflicting. BACP may expect confidentiality of client material. Managers may be expecting to have feedback on how clients are progressing with their counsellors. If training courses are added into the exercise, tutors may be requiring, for example, that their trainees have a certain number of on-going clients. A placement agency may be concerned about waiting lists and create a policy of time-limited work. Although, back in real life, such an issue is not the supervisor’s responsibility, he may be the person who becomes aware of such clashes, and who is at the centre – concerned for clients, trainees, the agency and proper ‘professional’ work. If group members are in contract with different agencies or courses, these differences are crucial to the focus of the supervision work.

So the profession, the client and any concerned organization, agency or training course are all stakeholders. Supervisor and supervisees need to be aware of these interconnections and know how and where they are accountable for the counselling work and the supervision undertaken.

Clearing the ground – models, orientations and frameworks

Terminology can be confusing in writing this complex supervision drama. In this book the word ‘model’ will be used in one way only – that is, to describe a comprehensive concept, or map, of supervision or of group supervision. The Supervision Alliance Model (Inskipp and Proctor 1995, 2001), which is referred to in the Introduction, and underlies the group model used in this book, is an example of this use of the word. Others are the SAS (Systems Approach Supervision) Model (Holloway 1995) or the Cyclical Model (Page and Wosket 1994). These focus on some concept which is central to the core beliefs on which the model is based and seek to map the process of supervision in its widest sense.

A model offers a mental map for ordering complex data and experience. Within each model are specific ‘mini-models’. In this book, the noun used from time to time to describe such a concept – a ‘map within a model’– is ‘framework’. So, the framework of tasks of supervision within the SAS Model (Holloway 1995) is the development of:

- counselling skills

- case conceptualization

- professional role

- emotional awareness

- self-evaluation

The framework for tasks within the Supervision Alliance Model sees the responsibility for supervisor and supervisee as:

- formative – the tasks of learning and facilitating learning

- normative – the tasks of monitoring, and self-monitoring, standards and ethics

- restorative – the tasks of refreshment

In Houston’s (1995) model, the tasks framework is:

- policing

- plumbing

- (making) poetry

In Carroll’s (1996) Integrative Generic Model the task framework is:

- creating relationship

- teaching

- counselling

- monitoring

- evaluating

- consulting

- administration

In this terminology, the well known Process Model of Supervision (Hawkins and Shohet 1989) (referred to later) would be a framework for focusing in supervision.

To distinguish these from the broad theoretical concepts, or ‘schools’ of counselling and psychotherapy practice which are often called ‘theoretical models’, I will refer to the latter as ‘theoretical orientation’. It may well be that some supervisors describe their ‘model of supervision’ by the theoretical orientation in which they work, for example ‘the psychodynamic model of supervision’. Carroll has pointed out (1996) that writers about supervision are increasingly moving away from ‘counselling bound’ models to models based on social roles, developmental stages and so on.

One framework or map, within the Group Supervision Alliance Model, that will frequently be referred to, denotes specific ways of conceiving the roles and responsibilities in group supervision. For ease, these will be described under types. You will read about Type 1 (or 2 or 3 or 4) groups. (The fuller name and description of each type will be given later in Chapter 3.)

As the founders of Neurolinguistic Programming quoted: ‘The map is not the territory’, and as Psychosynthesis has it, ‘This is not the truth.’ Models, maps, frameworks, orientations, types are the labels and descriptions devised to order and communicate our experience. In this book they are used as a preliminary. I would like the book to be useful in introducing, or re-introducing, you to the territory of group supervision. It can then be used not only to map (and encourage map-making), but also to guide and serve as a practical and psycholog...