eBook - ePub

Interviewing for Social Scientists

An Introductory Resource with Examples

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Interviewing for Social Scientists

An Introductory Resource with Examples

About this book

Students at postgraduate, and increasingly at undergraduate, level are required to undertake research projects and interviewing is the most frequently used research method. Interviewing for Social Scientists provides a comprehensive and authoritative introduction to interviewing. It covers all the issues that arise in interview work: theories of interviewing; design; application; and interpretation. Richly illustrated with relevant examples, each chapter includes handy statements of "advantages" and "disadvantages" of the approaches discussed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1Interviews and Research in the Social Sciences

. . . there is a very practical side to qualitative [research] methods that simply involves asking open-ended questions of people and observing matters of interest in real-world settings in order to solve problems. (Patton, 1990: 89)

This is a chapter about the theories behind interviewing, which is one, immensely popular research method in the social sciences. It is also a deceptive method, for, since we have read, seen and heard hundreds of interviews in the press, on radio and on television, it is easy to be blase about them and to assume that interviewing is nothing more than common sense at work.

For that reason, and because this chapter deals in some complex, difficult and contested ideas, there may be a temptation to skip this chapter, a temptation that is both understandable and regrettable. Regrettable, because it is here we argue that interviewing is a family of research approaches that demand method more than common sense; and that approaches to interviewing are influenced by the purpose behind the research and by our often unvoiced assumptions about the nature of social science. Furthermore, choosing to interview might mean choosing not to use other research techniques, and that is a decision that needs to be justified.

Much of what we say in this chapter holds good for social science research in general. The same could be said of Chapter 2, in which we outline a common social science technique called triangulation and suggest that interviewing may be used in conjunction with other methods. Chapter 4, which is about the design of an interview study, also addresses issues that arise in designing any social science research.

In each of these chapters, for the sake of completeness, we have introduced some terms, such as reliability and validity, before dealing with them in depth. In those cases we have given references to the pages on which they receive fuller treatment.

Throughout, our position is that research methods may be, and often are, applied atheoretically. Their power is greater when methods, such as interviews, are chosen because they are the best for the purpose, and when that choice is consistent with an understanding of what social science is and is not. (We are not saying that there is only one understanding. We are saying that it is important to have an understanding of what social science can and cannot do.)

So, while we see the sense in what Patton is claiming, in this chapter we shall sketch the reasons why you need to be thoughtful as an interviewer. Our stance is that people’s perceptions of the world are more or less individualistic and that different interviewing approaches are suitable for documenting perceptions that are widely shared from those used when exploring more personal, individualistic understandings. That involves a foray into the large debate about the nature of social science itself. Having surveyed this ground, we open a recurrent theme of this book, namely that interviews are one social science research method and will frequently be used alongside others. Since different methods have different strengths and different limitations, the choice of method(s) is a fundamental one in any social science enquiry. Just as you cannot drive a nail into wood using a screwdriver, so too the choice of methods in social science enquiry limits the types of conclusions you will be able to draw.

Interviewing in the social sciences

Interviewing, we suggest, is not a research method but a family of research approaches that have only one thing in common – conversation between people in which one person has the role of researcher. We understand ‘research’ to be ‘systematic enquiry’, so there is no implication in the use of the term ‘researcher’ that the interviewer wears a white coat and horn-rimmed glasses, holds a clipboard, talks jargon, scribbles illegible notes and dominates proceedings. Rather, we claim that choosing the most appropriate interviewing approach is a skilled activity, one that involves taking a stance on some complex and important debates about the nature of research in the social sciences.

Interviewing has a lot in common with questionnaire-based methods1 and, taken together, they dominate social science research. Interviews are also widely used in other disciplines and for other purposes. Some historians of modern times use them in oral history work. Interviews are also used in helping and caring professions for diagnostic and counselling purposes, although we will not give systematic attention to therapeutic and diagnostic interviewing.

We do not see interviewing as a straightforward activity, although there are dissenting voices in the research community:

The overwhelming majority who have thought about [interviewing as a research method] have concluded that interviewing is overwhelmingly based on common-sense activities and therefore, we might as well accept the inevitable and do it without thinking much about how we do it, just as everyone does common-sensically. (Douglas, 1985: 12)

However, we argue that research has most power when the choice of methods is deliberate and, where interviews are one of the chosen methods, where full thought has been given to our goals and to the type of interviews that we will use: these are complex decisions that shape the potential meanings of our findings.

Similarity and difference in human affairs

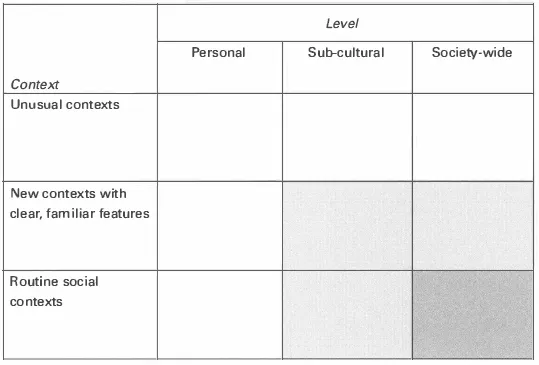

Interviews may provide data on understandings, opinions, what people remember doing, attitudes, feelings and the like that people have in common (survey interviews). They may be more exploratory and qualitative (qualitative2 interviews), concentrating on the distinctive features of situations and events, and upon the beliefs of individuals or sub-cultures. This continuum from convergence to divergence is represented by the increasing depth of shading in Figure 1.1.

Underlying that figure is a constructivist view of knowledge. The claim is that perception, memory, emotion and understanding are human constructs, not objective things. Yet, this construction is not a chaotic process because it takes place within cultural and sub-cultural settings that provide a strong framework for meaning-making. So, we share similar (but not identical) understandings of things that are common experiences and subject to society-wide interpretations. We have similar understandings within our society of law, school and work. However, we also bring to each of these an understanding that has personal elements. Nevertheless, in the lower right-hand corner of the grid, meanings are more even and predictable. Consequently, it is often appropriate to use surveys to investigate their incidence and salience. As we move to more personal events, such as falling in love, then understandings and the meanings that go with them, although they are still socially shaped, are likely to become more diverse. Furthermore, if we encounter a fresh situation, then the understandings we construct are less governed by social rules, social norms and social conventions, and are more likely to be more individualistic. Here, we would need to use more qualitative approaches to try to understand the nature and effects of these meanings.

FIGURE 1.1 The sequence from light to dark shading indicates the continuum of understanding from individual and distinctive to more shared and communal. The same movement could also be described as one from relativist to positivist perspectives.

Interviews can explore areas of broad cultural consensus and people’s more personal, private and special understandings. However, different research designs will be needed to see how many people intend to vote for a particular political party (an example of what is called survey research) and to try to find out why so many young people have unprotected sex (which may need more qualitative research). In the first case, there is a wish to claim that what we have found out about the sample is likely to hold good for voters in general. This is called generalizing from a sample to the population and depends on carefully selecting a sample that reflects key characteristics of that population. This might also be described as quantitative research, since the intention is to collect data that can be analysed so as to give a numerical description of the sample’s voting intentions. Quantitative research is designed to produce conclusions in the form of numerical data, and typically uses ‘closed’ questions. Box 1.1 contains examples of closed and open questions, and the topic is revisited in Chapter 7. Surveys are the most common form of quantitative interview research.

In the second case, the intention is to explore meanings, and the sample might be far smaller and generalization would not be the researcher’s main goal. The sampling technique might be quite opportunistic, and involve asking one informant to nominate others who might be worth talking with (this is sometimes called ‘snowball sampling’). The interviewer would be anxious to listen to informants’ accounts of their behaviours, beliefs, feelings and actions and would probably ask open-ended questions, rather than ask questions that invite precise answers that can be tallied to provide numerical summaries. The data do not easily yield any conclusions that can be put in a precise numerical form and some workers in the qualitative research tradition go so far as to argue that numerical data should not be extracted from such qualitative research (for example, McCracken, 1988). The interviewers would probably complement their conclusions with recommendations about policy, or with suggestions about directions that future research might take. That further research might take the form of a survey involving a carefully designed sampling technique, with the intention of making general statements on the basis of the findings.

Table 1.1 illustrates the key, surface differences between survey and qualitative research. These differences can be exaggerated, and researchers often draw upon features of each approach when designing a study, even though the two approaches rest on very different assumptions about the social world and the nature of human understanding of it.

Interviews and structure While surveys tend to be highly structured, with a precise interview schedule that the researcher has to follow closely, qualitative interviews are less structured. Table 1.2 indicates the relationship between the type of research and the degree of structure imposed on the interviewer. Table 1.3 gives a more detailed picture of the differences between structured and unstructured interviews, while also identifying characteristics of semi-structured interviews.3 These themes are also addressed in Chapter 7.

Structured interviews produce simple descriptive information very quickly. So, for instance, it would be relatively easy to find out how many people smoked, what brand of cigarettes they used and to get an (under)estimate of how many cigarettes they smoked. (People tend to under-report their less socially acceptable behaviours and to over-report those that are more desirable.) However, points of interest explaining why people continued to smoke knowing that it was bad for their health, the significance and meaning smoking held for them, would not come to light. Structured interviewing is often used as a precursor to more open-ended discussion, or alternatively afterwards to ascertain whether hypotheses generated during qualitative interviews are statistically verifiable.

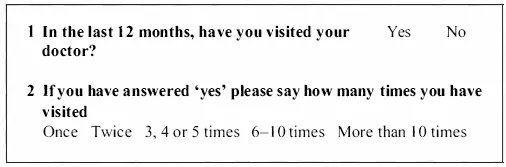

Box 1.1 Closed and open questions

Survey research is intended to produce data that can be neatly and reliably summarized by numbers, tested for statistical significance and represented in charts.

Closed questions are normal. For example:

Qualitative research is less interested in measuring and more interested in describing and understanding complexity. Here, open questions are normal, although closed questions are often asked to collect background data (for example, about career, health history, attitudes, cognitive styles). Open questions let informants respond in their own words. For example:

- What have been the most interesting things about your new job? [...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Boxes

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- 1 Interviews and Research in the Social Sciences

- 2 Triangulation in Data Collection

- 3 Why Interviews?

- 4 Designing an Interview-Based Study

- 5 Feasibility and Flexibility

- 6 Approaches to Interviewing

- 7 Achieving a Successful Interview

- 8 Interviewing in Specialized Contexts

- 9 Protecting Rights and Welfare

- 10 Transcribing the Data

- 11 Meanings and Data Analysis

- 12 Writing the Report, Disseminating the Findings

- Appendix: An Interview Research Checklist

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Interviewing for Social Scientists by Hilary Arksey,Peter T Knight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.