![]()

It would not be correct to say that every moral obligation involves a legal duty; but every legal duty is founded on a moral obligation.

Lord Chief Justice Coleridge in R v Instan [1893] 1 QB at 453 (in Mason and Laurie 2006)

In the Introduction, there was a glimpse of how one situation can give rise to a wide variety of rights, duties and legal actions in both criminal and civil law. This chapter explores how some of the different areas of law relate to each other. We also explore the legal system in England and Wales in 1.2 below. This book covers Northern Ireland, Scotland and other jurisdictions where specifically stated.

As an illustration, imagine an alleged breach of confidentiality where a therapist working in an Employee Assistance Service accidentally addresses a letter about a client to the wrong person. The letter contains sensitive information relevant to the client’s credibility and reputation as an employee. This mistake could put the therapist in breach of contract with a client (and her employer) and be the basis of multiple civil wrongs, including breach of her duty of care. Suppose, then, that the therapist, by now very frightened at the potential consequences of her actions, goes further and, when accused of these civil wrongs, offers a fabricated defence that the letter had been stolen and then maliciously addressed by a person (whom she names as the thief) to cause maximum harm. Suppose the therapist also removes documents from her employer’s files to hide traces of her own actions. Suddenly we are in the realms of slander, and the criminal offence of theft of the documents and possibly also attempting to pervert the course of justice. Each single action (or a sequence of closely related actions) may create liability in different areas of law and each will have its own specific court, rules of evidence, and type of hearing. The evidence in any civil action may also be used in any criminal prosecution that might be brought, and the evidence of conviction from a criminal hearing might be used in evidence in a civil matter. Evidence from either or both might be used in any subsequent disciplinary hearings by professional bodies.

Understanding the difference between criminal and civil law is fundamental to understanding the application of law to the work of therapists. It determines which courts may be involved with their different rules and approach to evidence. We will return to this topic later. However, we will start with the most basic of questions about what is the relationship between law and ethics. This introductory chapter provides a context for the remainder of the book.

1.1 Law and ethics – relationships and differences

It is often difficult to know what is right. Moral evaluation is both collective and personal, and may be based on a vast eclectic mix which includes social, cultural, religious and family values. Ethics are the result of more systematically considered approaches to distinguishing what is right from wrong. Most professions have developed their own ethical statements as a way of explaining how their work is best undertaken to achieve the greatest good and minimise any potential harms or wrongs. These statements of ethics help professionals to consider the justification for the ways they approach their work.

For example, the Ethical Framework for Good Practice in Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP 2010) (the Ethical Framework) sets out shared values across the area of professional activity and provides guidance for conduct and best practice. See also the guidance provided by other associations including, for example, the British Psychological Society (BPS), the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP), the Confederation of Scottish Counselling Agencies (COSCA) and the government programme, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT).

Ethical frameworks are not law, and nor are they, in themselves, legally binding. However, as an expression of the shared values of the profession, they will carry weight within the profession to which they apply, for example, in the consideration of complaints and within disciplinary hearings. Courts may refer to ethical frameworks and to the codes of professional bodies in order to determine what that body has adopted as a reasonable standard of practice. As a result, professional frameworks or codes may have persuasive authority in court cases but no court is bound to follow their requirements.

The law is the system of rules by which international relationships, nations and populations are governed. Law reflects society’s prevailing moral values and beliefs, enforcing compliance in various ways, such as fines or imprisonment. It constantly changes and develops along with changes in society. For example, the legislation concerning corporal punishment, homosexuality, child protection, ownership of family property and smoking in public has changed radically over the years.

There are three legal national jurisdictions comprising the United Kingdom (UK), i.e. England and Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland. Eire (Southern Ireland) is a wholly separate nation state but has many legal features in common with the UK legal system. Similarly, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands each have their own law-making powers independently of the UK government. Although some of the legal systems and requirements are unique to each of these nations, there are broad similarities in the legal structures across this geographical region. Therapists need to be familiar with the legal systems and requirements applicable to the area in which they live and work.

1.2 Introduction to the legal framework in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

1.2.1 Legal structure

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (UK) consists of four countries, with three distinct jurisdictions, each having its own court system and legal profession: England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. The UK is part of the European Union and is required to incorporate European legislation into UK law, and to recognise the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in matters of EU law.

The Queen is the Head of State, although in practice, the supreme authority of the Crown is carried by the government of the day. The Queen is advised by the Privy Council. The government comprises the Prime Minister (appointed by the Queen), the Ministers with departmental responsibilities, and those Ministers of State who form the Cabinet by the invitation of the Prime Minister. The legislature comprises the two Houses of Parliament – the House of Lords and the House of Commons.

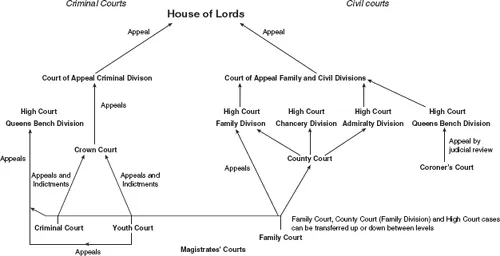

In the UK, the constitutional law consists of the Acts of Parliament, known as ‘statute law’, subordinate legislation ‘statutory instruments’ made under the authority of the Acts of Parliament, and case law (the decisions of the courts), in which the courts interpret and apply the statute law. In case law, there is a hierarchy of court decisions, known as ‘judicial precedent’, in which the decisions of the House of Lords bind every court below it (including the Court of Appeal) and the decisions of the Court of Appeal bind all lower courts. See Figure 1.1 for an illustration of the hierarchy of the courts in England and Wales. There are also constitutional conventions which have binding force but do not have statutory authority.

1.2.2 The courts system

The courts are divided between criminal and civil. Criminal cases concern breaches of public morality of sufficient seriousness for the courts to be given powers to impose punishment on behalf of the state. Civil cases are largely about relationships between citizens and especially resolving any disputes that may arise.

Criminal trials

The magistrates’ courts, which deal with minor offences, are the lowest criminal courts. More serious cases (trials on indictment) are committed for trial from the magistrates’ court to be heard in the Crown Court (Queen’s Bench Division). For discussion of disclosure of client notes and records, and giving evidence in criminal cases, please see Chapter 10 at 10.8, BACP Information Sheets G1 and G2 (Bond and Jenkins 2008; Bond et al. 2009), and detailed discussion in Bond and Sandhu (2005).

Figure 1.1 Hierarchy of the courts system in England and Wales and avenues of appeal

Criminal appeals

Subject to certain restrictions, a person convicted or sentenced in the magistrates’ court may appeal to the Crown Court against conviction and/or sentence. Bail decisions may similarly be appealed. Appeals in criminal cases lie from the Crown Court to the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division). In some situations, appeal also lies from the magistrates’ court or the Crown Court to the High Court, by way of ‘case stated’, that is requesting the magistrates’ court or Crown Court to state the facts of a case and the questions of law or jurisdiction on which the opinion of the High Court is sought, see s. 111(1) of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980, s. 28 of the Supreme Court Act 1981, and Part 52 of the Civil Procedure Rules 1998.

Civil cases

Therapists are probably most likely to be involved as witnesses in family or personal injury cases. Personal injury or negligence cases, like other civil matters (for minor claims), will at first instance be heard in the County Courts.

Parties who are dissatisfied with a judgment may appeal from the County Court to the High Court. More serious actions may be initiated in the High Court, which is divided into three divisions: Queen’s Bench, Chancery and Family. Civil cases from the High Court may be appealed to the Court of Appeal (Civil Division). Details of Her Majesty’s Courts Service and the work of the Tribunals can be found at www.hmcourts-service.gov.uk/.

The House of Lords is the supreme court of appeal. It has separate functions as a legislative body and as a court. Cases are heard by up to 13 senior judges known as the ‘Law Lords’. Information about the judicial work and judgments of the House of Lords can be found at www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/ld/ldjudinf.htm.

Children and family cases in the ‘Family Court’

All children and family matters are dealt with in the ‘Family Court’, a new system created by the Children Act 1989. It has three tiers, the Family Proceedings Court (magistrates’ level), the Family Division of the County Court, and the Family Division of the High Court. Cases can move up and down these levels as necessary. Child protection cases begin at the magistrates’ level but may be transferred up and down as appropriate. The magistrates can hear some family cases. Appeals from the Family Proceedings Court, and most divorce, contact disputes, and most ancillary relief (finance and property) matters, will be heard in the County Court. Some appeals may go to the Family Division of the High Court, Court of Appeal and House of Lords.

Tribunals

In addition to the courts, there are specialised Tribunals, which hear appeals on decisions made by various public bodies and Government departments, in areas including employment, charities, immigration and social security, and the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board, which adjudicates on compensation for injuries caused by criminals.

The courts system in Scotland

The courts system in Scotland is completely different from the system in England and Wales. Criminal cases are heard by the District Court, the Sheriff Court or the High Court of Justiciary, depending on the severity of the offence concerned. Serious cases, such as rape and murder, are dealt with at the High Court. The High Court of Justiciary also sits as an appeal court and determines criminal appeals. There is no right of appeal to the House of Lords in Scottish criminal cases, although there may be an appeal to the Privy Council in some circumstances.

Civil cases are heard at either the Sheriff Court or the Court of Session. Typically, the Sheriff Courts (situated throughout Scotland) deal with disputes of a lesser value. Cases of a high value are usually raised in the Court of Session in Edinburgh. The House of Lords is the supreme court of appeal in Scottish civil cases. Matters relating to child and family law can be dealt with in the Sheriff Court or in the Court of Session. Scotland also has a specialised Children’s Hearings system with offices throughout the jurisdiction, dealing with certain matters relating to children. Employment Tribunals proceed in Scotland in the same way as in England.

1.2.3 Criminal and civil law

Law is often noticed in terms of crime, but in fact, the legal system comprises two sub-systems – civil and criminal law. The area covered by civil law is vast, regulating many aspects of our life and work. Glanville Williams refers to the distinction between a crime and a civil wrong as follows:

… the distinction does not reside in the nature of the wrongful act itself. This can be simply proved by pointing out that an act can be both a crime and a civil wrong … but in the legal consequences that follow it. (sic)

He added, by way of explanation to law students:

If the wrongful act is capable of being followed by what are called criminal proceedings, it is regarded as a crime. If it is capable of being followed by civil proceedings, that means that it is regarded as a civil wrong. If it is capable of being followed by both, it is both a crime and a civil wrong.

(Glanville Williams 1963: 6)

An example of this might be a therapist who makes unwanted physical sexual advances to a client, which may constitute the criminal offence of assault (and also possibly a sexual offence), and may also give rise to a civil action for personal injury for the assault and any traumatic stress involved, not to mention grounds for complaint within the professional conduct procedure.

Criminal and civil proceedings are brought in different courts, with different procedure and terminology. Information can be found on the Lord Chancellor’s website for citizens at www.direct.gov.uk/en/index.htm. Please see Chapter 10 on how to deal with legal claims in the various different courts.

Criminal law

Following a police investigation, the Crown Prosecution Service advises the police on evidence and law, and prepares the case for prosecution. The parties are referred to as the prosecutor and the defendant, or the accused.

Criminal cases are brought by the monarch against those accused, and so currently, they are referred to in court verbally as ‘The Queen against … X’. This is written down as R (short for ‘Regina’ or ‘Rex’, meaning the Queen or King) v X (the defendant’s surname or initial) with the date and the references for the various law reports in which they can be found, e.g. R v H (Assault of Child: Reasonable Chastisement) [2001] EWCA Crim 1024; [2001] 2 FLR 431.

In Scotland, cases are brought at the instance of the Crown in the High Court by Her Majesty’s Advocate. They are reported as ‘HM...