![]()

1 | Meanings of democratic leadership |

The essence of democracy is how people govern themselves, as opposed to how they are governed by others (Williams 1963: 316). It is a hotly debated issue that has generated a large variety of meanings concerning the nature of democratic societies, organisations and groups (Held 1996; Saward 2003). Different conceptions of democracy imply differing conceptions of the individual and of human purposes, of norms and values and, not least, of the aims and significance of education. Some conceptions of democracy are narrow, such as liberal minimalism, one of the models of democracy discussed below. Others are broad. Carr and Hartnett, for example, describe the classical conception as a ‘critical concept incorporating a set of political ideals and a coherent vision of the good society’ (1996: 53) and encompassing a substantive conception of the person. This chapter, having briefly considered the origins of modern democracy in the democratisation of access to religious knowledge, discusses models of democracy which are progressively richer and more challenging, culminating in the developmental model.

A modest narrative

The origins of modern democracy lie in the recognition that neither the capacity nor the right to interpret the most important truths are necessarily confined to an elite. Indeed, seeking the true and good path came to be conceived as an obligation of everyone. The roots of the Western conception of democracy lie in the idea that the generality of people are able to detect and discriminate between fundamental values which give meaning to life and place into perspective transient, mundane passions. The religious revolution of the Reformation advanced the proposition that everyone has the capability of accessing truths about God. The notion of dispersed, individualised authority is encapsulated in Martin Luther’s idea of ‘a priesthood of all believers’ (Hill 1975: 95). Overcoming the fear that one’s salvation is in the hands of an ecclesiastical elite, to whom deference is required in order to avoid eternal punishment, paved the way for democratic ideals. As one historian put it, ‘Theories of democracy rose as hell declined’.1 And as Richard Coppin, an itinerant preacher in the seventeenth century claimed – anticipating British Idealism and the developmental model of democracy which we examine below – God is within each person, and God is both teacher and learner (op. cit.: 221). For many believers – too many – their truth became the final truth – the truth that everyone else ought to embrace, even be compelled to accept.

The deeper breakthrough, however, was the surrendering of theological finality and the democratisation of religious knowledge. This democratised access to truth was not intended to be an individualistic licence declaring all opinions as equally true. Hill observes: ‘Emphasis on private interpretation was not … mere absolute individualism. The congregation was the place in which interpretations were tested and approved … a check on individualist absurdities.’ (1975: 95; see also Hill 1997: 101–2)

This is a ‘story’ of a turn in social development towards democratic governance, which we should see as a modest narrative rather than a grand narrative.2 There are other narratives – non-Anglo-Saxon, non-Western – about participation, shared leadership and democracy, which are to be valued and explored and which will be relevant in some or many educational contexts. For example, amongst the Bagandan people of Uganda, democracy is translated as obwenkanya na mazima, which means ‘treating people equally and truth’ and places the emphasis on being dealt with fairly and equally (Suzuki 2002). Wolof speakers in Senegal have added to the Western-derived association of democracy with elections and voting, an emphasis on consensus, solidarity and even-handedness (Saward 2003: 112–13). Islamic scholars debate the relationship between Islam and democracy, one viewpoint being that the association of the two is inevitable as Islam has an inherent theoretical affinity with the rule of law, equality and community involvement in decision making (op. cit.: 111–12). Much can be learnt from what is common and different amongst diverse understandings of democracy.

It is sufficient here, however, to note the importance of roots in the religious and political revolution of the seventeenth century. This is not because democracy has progressed steadily and smoothly from that point. Rather, what is crucial is that this modest narrative reveals the emergence of an awareness of something crucial to the idea of democracy. The modest narrative marks the breakthrough, or at least the beginnings of a breakthrough, of the person as creative agent. As Touraine puts it

Democracy serves neither society nor individuals. Democracy serves human beings insofar as they are subjects, or in other words, their own creators and the creators of their individual and collective lives. (1997: 19)

Moreover, democracy is anchored in a particular philosophical anthropology – a particular idea of what it means to be human and of the potentialities in human beings that make them human. For Marx, the creativity of humankind was the essential spark which made humanity what it is and, more significantly, what it could become. The problem in societies prior to the revolution envisaged by Marx is that the products of that creativity are out of human control. Humankind, most especially under capitalism, is alienated from its own character.

Man’s self-esteem, his freedom, has first to be reanimated in the human breast. Only this feeling, which vanished from the world with the Greeks, and with the Christians disappeared into the blue haze of the heavens, can create once more out of society a human community, a democratic state, in which men’s highest purposes can be attained. (Marx, quoted in Lowith 1993: 108)

The essential point to hold on to does not require acceptance of the theoretical details of Marx’s work, or indeed any particular religious perspective borne of the revolution in religion. Rather, the point is the intimate connection between democracy and creative human potential – and, more particularly, the potential for benign creativity. The latter is the very foundation of the broad and rich conception of democracy, which underpins the understanding of democratic leadership in this book.

The same might be said of democratic governance as Herbert Spencer said of republican governance: ‘The Republican form of Government is the highest form of government; but because of this it requires the highest type of human nature – a type nowhere at present existing.’3 Indeed, enrichment of people’s lives is integral to some of the most enduring strands of democratic thinking, back to Aristotle. This principle of democracy is

that society exists not merely to protect individuals but to offer them an enriched form of existence; so that a democratic society is one which seeks to provide positive rather than merely negative advantages to all its citizens and is to be judged by the degree to which it seeks, and is able, to do this. (Kelly 1995: 24)

Liberty for liberty’s sake is not the ultimate value. Some notion of positive liberty is implied (P.A. Woods 2003). Integral to broad and rich conceptions of democracy is some sense of unity around universal ideals, and respect for reason and the potentialities of all people to live the good life with others. It entails the development of human beings towards some common ideal. With this there is a danger within democracy – a dark side we might say. An idea of positive liberty entails an idea of what is good for people, which some may then feel justified in imposing on others. Thus, what originally begins as a celebration of human identity and creativity may lead to a domination of the individual by a detailed, prescriptive and imposed conception of what the true and good path is.

Bearing this in mind, it has to be emphasised that seeking a deep conception of democracy is a delicate and demanding project. Democracy requires ‘a sophisticated moral system which seeks to accommodate, even celebrate, moral and cultural diversity’ (Kelly 1995: 23). A balance needs to be sought between:

- unity (around a sense of common ideals);

- liberty;

- diversity (the ideals and identities that are integral to particular groups, cultures and societies).

The defining feature of democracy is

not simply a set of institutional guarantees of majority rule but above all a respect for individual or collective projects that can reconcile the assertion of personal liberty with the right to identify with a particular social, national, or religious collectivity. (Touraine 1997: 13–14)

Models of democracy

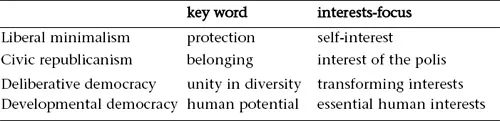

Table 1.1 summarises four models of democracy and their distinctive principles. These are based on Stokes (2002), who, from the array of theories of democracy, describes models which highlight the key characteristics, concerns and normative principles of the main types of democratic theory. Stokes’s own outline of the models provides a starting point. In discussion of each model, I elaborate from this starting point and suggest some of the model’s distinctive implications for thinking about leadership (see the right hand column of Table 1.1). The models are not entirely separate. Many of the concerns and normative principles carry forward from the narrower, more philosophically bare notions of democracy (starting with liberal minimalism) to be part of or combined with the broader notions (deliberative and developmental democracy). Hence, certain principles thread their way through all the models.

Liberal minimalism is a protective model of democracy. Its main purpose and justification is protection of the individual citizen from arbitrary rule and oppression from other citizens. Key importance is attached to procedures that curtail abuse of leaders’ power, based on an individualistic conception of human beings as ‘private individuals who form social relationships in order to satisfy their own personal needs’ (Carr and Hartnett 1996: 43). Formal equality of political rights is emphasised and the importance of procedures for choosing governments. This brings into the frame two fundamental principles that thread through all the models. The first is political equality. Democracy is about ‘the rule of equals by equals’ (Kelly 1995: 6), as citizens before the law. The second is liberty, which has a dual aspect (Berlin 1969):

Table 1.1: Models of democracy

- negative freedom (freedom of constraint imposed by other people);

- positive freedom (the wish to be one’s own master independent of external forces).

The model of liberal minimalism seeks to enable people to follow their interests in an ordered political and social framework, facilitating what C.B. Macpherson (1962) calls ‘possessive individualism’, which sees people as private owners of their own selves and of their own economic resources, protected by property rights (see also Olssen et al. 2004). Following Schumpeter, democratic politics is seen as ‘a competitive struggle analogous to the competition of the economic marketplace’ (Saward 2003: 44). It reduces democracy to a ‘political supermarket’ (Touraine 1997: 9). Leadership in liberal minimalism is confined to political elites competing for votes, and the main concern of leaders is to articulate and represent interests within society.

If we were to ask what is the key, distinguishing word associated with liberal minimalism, and what its prime interests-focus is, the respective answers would be ‘protection’ and ‘self-interest’. These are shown in Table 1.2, together with the key words and the primary interests-focus of each of the other models, which will emerge from the discussion below.

Table 1.2: Key words and interests-focus of models of democracy

Because of the minimal democratic activity ascribed to citizens and assumptions of self-interest, an assumption shared with economic theories of markets, liberal minimalism can evolve into a notion of consumer democracy. If political participation is minimal, a logical step is to attach greater significance to where people are more active in modern society – namely, as self-interested actors in the market. Consumer democracy reinterprets the main focus of democracy, by shifting it from participation in politics to participation in the market. In this interpretation, people achieve influence primarily as consumers who convey their needs and preferences through their buying decisions. Such a view has influenced educational policy in countries such as the UK, New Zealand and the USA. Grace sums up well the central assertion of proponents of this view: ‘Market democracy by the empowerment of parents and students through resource-related choices in education has the potential … to produce greater responsiveness and academic effectiveness’ (1995: 206). But this kind of assertion redefines democracy: ‘Freedom in a democracy is no longer defined as participating in building the common good, but as living in an unfettered commercial market …’ (Apple 2000: 111).

Civic republicanism is about belonging. It emphasises interests and concerns beyond the individual or family. Its defining features are ‘the importance given to the public interest or the common good … and [the] key role given to citizen participation’ (Stokes 2002: 31). Identification with the political community (paradigmatically the nation state) is also central. Political participation by citizens is valued for its own sake. Indeed, engagement in political debates and other activities is considered a civic duty. Leadership in civic republicanism involves encouraging political participation and dialogue, and seeking to identify that which serves the public interest of the political community.

The deliberative and developmental models assimilate key features of the first two theories, such as the importance of rights and procedures that protect individual citizens (liberal minimalism) and the active role of citizen participation (civic republicanism). But they enrich democratic theory by augmenting these, as will be seen in the discussion of each of these models.

The deliberative model is about the collective search for unity amongst diversity. It arises from the most recent contributions to democratic theory, having been ‘the dominant new strand in democratic theory over the past ten to fifteen years’ (Saward 2003: 121). Its concern is that existing arrangements ‘do not address sufficiently the various problems, including those of pluralism, inequality and complexity, that are a condition of contemporary society’ (Stokes 2002: 39–40). Its aim is to expand ‘the use of deliberative reasoning among citizens and their representatives’ (p: 40) and enhance the quality of deliberation. Deliberative democracy entails individuals, in cooperation with others, seeking out the greater good for themselves and the community. This means reaching beyond one’s own narrow perspective and interests, and being strengthened by this shared endeavour.

By now we have moved a long way from the competitive and minimal participation of liberal minimalism. Differences of view and conflicts of interest are recognised, but ways also have to be found to overcome them. Deliberation implies recognition of the interconnection of identity and difference. The one (identity with a national society, for example) implies the other (differences as and...