- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This comprehensive textbook provides a clear nontechnical introduction to the philosophy of science. Through asking whether science can provide us with objective knowledge of the world, the book provides a thorough and accessible guide to the key thinkers and debates that define the field.

George Couvalis surveys traditional themes around theory and observation, induction, probability, falsification and rationality as well as more recent challenges to objectivity including relativistic, feminist and sociological readings. This provides a helpful framework in which to locate the key intellectual contributions to these debates, ranging from those of Mill and Hume, through Popper and Kuhn to Laudan, Bloor and Garfinkel among others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Philosophy of Science by George Couvalis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Geschichte & Theorie der Philosophie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Theory and Observation

It is widely believed that many scientific theories have been justified objectively and that we know they give us a true picture of the world. In contrast, the claims of philosophers and the pronouncements of religions, no matter how plausible, are widely believed to be speculative and dubitable. The belief that many scientific theories have been justified objectively is allied to the view that scientific theories can be justified by observation because observation gives us direct access to the world. Taking this view, science provides an ideal method for acquiring knowledge which should be emulated whenever possible – the answer to the central problem of epistemology, ‘how can we get knowledge?’, is ‘follow the methods of science as much as possible’.

A radically different view of observation holds that all observation is deeply permeated by theories, so it does not provide us with direct access to the world. This is the view that all observation is theory-laden. Arguments for this view have been put by many philosophers.

If all observation is theory-laden, the objectivity of scientific research might be undermined, for it seems that we may well be unable to tell whether our perceptions accurately capture aspects of the world. To deal with the problem of whether scientific theories can be justified objectively, I need to consider the three main claims which are used to support theory-Iadenness and discuss their consequences. These three claims are:

1all experience is permeated by theories;

2theories direct our observations, tell us which observations are significant, and indicate how they are significant;

3all statements about what we observe are theoretical and cannot be derived from our experience.

I shall argue that these claims are incorrect or misleading but, even if they were correct, scientific theories could be tested objectively.

1 The influence of theory on experience

The arguments for the theory-ladenness of experience

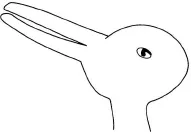

The first claim is that all experience is permeated by theories. This claim is often defended by pointing out that our experience sometimes dramatically changes, even though the perceptual stimulus remains the same, and arguing that this change is dependent on interpreting the stimulus theoretically. Consider the famous case of the duck-rabbit (see figure 1.1). The drawing remains the same, yet it will sometimes look like a picture of a duck and sometimes like a picture of a rabbit. Many people find that they can easily make the image look like one or the other. This seems to indicate that our ideas about what we want to see, or about what we expect to see, change how things look. It seems that those who want or expect to see a duck, see a duck, and that those who want or expect to see a rabbit, see a rabbit. Apparently we can change from seeing a duck to seeing a rabbit merely by changing what we want or expect to see.

Figure 1.1 The duck-rabbit drawing

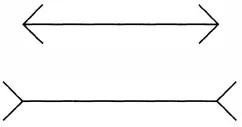

A second argument for the first claim points out that sometimes the way an item looks does not reflect how it really is and argues that the best explanation for this phenomenon is that theories permeate experience. A famous case of this kind is supposed to be the Müller-Lyer illusion (see Figure 1.2). People typically report that the two lines look like they are of different length. But if we measure them with a ruler, we find that they are of the same length. It is often said that our beliefs about rooms with right-angled corners lead us to experience the Müller-Lyer diagram in a false way, that is, we have come to expect lines with corners with certain angles to be further away than they really are, and hence to look smaller. Some researchers have claimed that certain groups of people in Africa do not suffer from illusions like this one. They suggest that perhaps the different background of such people means that they have theoretical beliefs which make them immune to those illusions.1

Figure 1.2 The Müller-Lyer illusion

Some philosophers have said that illusions like the duck-rabbit and the Müller-Lyer show that the effects of theories deeply affect scientific observation. For example, they maintain that Copernicus and Ptolemy really had quite different experiences when they watched the sunrise. Because Copernicus believed the horizon falls, his experience was of the horizon falling; because Ptolemy believed the sun rises, his experience was of the sun rising (Hanson, 1958). If these philosophers are right, then it appears to be impossible to test theories objectively, for it is impossible to appeal to observations which have not been contaminated by the very theories which are supposed to be tested through experience. Both Copernicus and Ptolemy may have thought their theories were justified by how the world looked, but the way the world looked would have been so deeply affected by their theories that it would be impossible to tell whether what they were seeing was a product of their theories or a feature of the world.

Critical discussion

My first criticism of the claim that experience is penetrated by theory is, even if it is correct, there are limits to perceptual plasticity and this means that many theories can still be objectively tested through experience. We can make the duck-rabbit drawing look like a drawing of either a duck or a rabbit, but simple experiments the reader can carry out will show that we cannot get it to look like much else. No matter what we expect to see or want to see, we cannot get the duck-rabbit drawing to look like the Parthenon, the Sydney Opera House or a teacup. We cannot even make it look like a real duck as opposed to a drawing of a duck. This means the claim that the duck-rabbit drawing is really the Parthenon is refuted by experience; no matter how hard we might try to make the drawing look like the Greek building, we fail (Brown, 1979: 93–4).

My second criticism of the arguments for the theory-Iadenness of experience is that, in any case, a perceptual stimulus can only be plausibly said to be capable of looking more than one way in situations in which we are either perceiving a two-dimensional item (such as a drawing) as a representation of something else or perceiving something under poor conditions (for example, when we see an object at night or when we examine it quickly). That our experience is untrustworthy under poor conditions does not imply that it is always affected by theories, and so does not imply it cannot be used to test theories objectively. In situations in which we carefully examine something in bright light, walk around it, etc., we seem to be unable to make the object look different. In such situations, our experience can be used to objectively test theories. This does not mean, of course, the appearance of things is never deceptive under ideal conditions – perhaps a stick seen through clear and well-lit water will look bent. However, it does mean that our beliefs are not determining the way things look, so at least one source of error can be eliminated.

This second criticism finds some support in everyday experience, but its force may be thought to be blunted by the fact that much of science relies on observations which are not made under ideal conditions. When we study the planets or tiny objects, we often use telescopes and microscopes which do not present us with bright and sharp three-dimensional images. In such cases, we have to practise to make the images at all crisp. It may be argued that we need to use theory to make our images crisp and, as a result, we can unwittingly make our images include things which do not exist. This may explain, for example, why Galileo, though an experienced observer, drew two large moons rather than rings when looking at Saturn. Thus, a sceptic about science may say there is a serious problem in trying objectively to test theories about distant or small objects through experience, as our observations of such objects are contaminated by our preconceptions.

However, I can strengthen my second criticism to deal with this problem. First, when images sharpen as we practise, it is not at all clear whether theory plays an important role. In the absence of other evidence, it is just as plausible that the changes are brought about solely by localized mechanisms in the eye or brain which adjust over time. To understand this point, consider the parallel case of entering a dark room after being in bright sunlight. At first we cannot see anything clearly, but after a while we begin to distinguish various objects; yet this process seems to have nothing to do with theory. Second, even when theory seems to play some role, for example when our visual field changes to include the white blood cell in the upper left comer of the slide after we have been told to look for it, it is not clear that the theory is acting as anything more than a device for directing our attention to a particular area – something which we might have done anyway given more time or which could have been done by shining a bright light on that spot. (Note that I am only talking about experiencing the blood cell, not about knowing that it is a blood cell.) There is no evidence that theory problematically permeates experience as opposed to merely helping us focus on some aspect of the world. Third, examples which are supposed to show that we see images of non-existent things when we expect to see them, may well tum out to be examples of us compensating for the lack of sharpness of images through our descriptions and not of us changing experience through belief. (It might well be the case that Galileo, who was using a telescope which focused badly and produced a great deal of chromatic aberration, could not resolve the image of Saturn’s rings and guessed that they were moons.) Anyone who has used a telescope or microscope knows that some images simply will not resolve and that frustration can lead us to fudge results.

My three subsidiary arguments imply that there is no good reason to believe that careful observations through instruments are contaminated by theories. As far as we can tell, scientists can objectively test theories about small objects and about distant objects by relying only on stable and sharp images produced by instruments and by resisting the impulse to fudge results. To strengthen my three subsidiary arguments, I need to move on to my third criticism of the first claim, which is: the best explanation available of changes in the way a stimulus looks says that such changes have nothing to do with theory. This explanation has been developed in detail by Jerry Fodor, so I shall turn now to his story.

Fodor begins by pointing out that when we experience items in a way that has been distorted by mental processes, the evidence indicates the distortions do not depend on one’s beliefs. He argues this means that theory-ladenness is refuted and not supported by such experiences. He concentrates on the Müller-Lyer illusion, though his argument applies to similar cases: whether we believe (hold the theory that) the two lines are equal or unequal when we observe the Müller-Lyer diagram, they continue to look unequal. This means our beliefs cannot be causing them to look unequal.

Fodor explains the illusions in question by using his modularity theory of mind which, he claims, better fits the empirical evidence than explanations which involve theory-Iadenness. According to the modularity theory, the mind has separate modules which process information. Modules cannot be influenced by other modules in their basic functioning (which is either innately specified, or partly innately specified and partly specified by environmental training) – Fodor makes this point by saying modules are encapsulated. Information can be acquired from such modules by a central processing unit which has linguistic beliefs and can make reasoned judgements about such information, but the kinds of reports the modules give are not affected by those beliefs.

An example of a module might be the visual processing system. By Fodor’s account, this module is either hard-wired or becomes hard-wired through training in a particular environment. It can be directed by the central unit to give information about what is happening in a particular spatial area, but the perceptual reports it gives are not influenced by the beliefs of the central unit. For example, people brought up in an environment with lots of corners with 90° angles, such as rooms in modern Western buildings, may suffer from the Müller-Lyer illusion; on the other hand, people brought up in round African huts may not. It may be possible to make the African people suffer from the illusion by making them move about in Western rooms for some time, but this would have nothing important to do with their beliefs about those rooms. A young cat’s visual module would also adjust to our rooms over time through being trained in them. The key point is that the adjustment does not occur through a top-down process in which the language module passes the ‘correct’ theory to the visual module.2

Fodor thinks the most plausible explanation of why illusions are recalcitrant is that it is .useful for the survival of animals to have fairly unintelligent and quickly functioning perceptual processing modules. Such modules provide experiences which tend rapidly to fix true beliefs about the world. Linguistic beliefs are subject to all sorts of speculative theoretical influences and if such beliefs affected all experiences, animals would have trouble surviving (Fodor, 1984).

Fodor’s account occupies a kind of middle ground between a simplistic empiricism which sees perception as unintelligent absorption of information and a view which holds that highly intelligent processing systems transform perceptual stimuli. The modular units which provide us with perceptual information are intelligent in the sense that they process perceptual stimuli. This means our perception is structured in various ways. However, the modular units do not use theories in the central processing module to structure information.

At first sight it would seem that Fodor has difficulty in explaining how certain items, such as the duck-rabbit drawing, sometimes seem to look one way and sometimes the other. A plausible explanation of this phenomenon is that our belief that we see a drawing of a rabbit makes it look like a rabbit. However, Fodor argues that a better explanation is that the change in the apparent image is triggered by changing the point on which we focus (1988). By focusing on one point we make the image look like what English speakers call a rabbit-like image, while by focusing on another point we make it look like what English speakers call a duck-like image – whatever we believe (and even if we have never heard of ducks or rabbits!). Fodor’s argument here implicitly relies on well known psychological evidence that our ability to change illusions is, at least, inhibited when we cannot change the point on which we focus.

The details of Fodor’s proposal are controversial as subjects can make illusions decrease in intensity, a phenomenon which requires explanation.3 For our purposes, however, we can ignore these controversies and concentrate on the arguments for the encapsulation of the mechanisms involved. For Fodor to criticize theory-Iadenness, it would be sufficient for him to show that the mechanisms do not seem to be affected by our theories. I take it that the sorts of theories we have in mind here are fairly general views about the world which are articulated, or presuppositions of such views which are not articulated but which are clearly present.4 An example would be Copernicus’s theory. Fodor makes two claims: first, there is no evidence that holding Copernicus’s theory affects one’s experience, and second, the recalcitrant nature of one’s experiences suggests the opposite. Fodor’s account is consistent with the fact that if we concentrate on the horizon when the moon is rising, the moon will seem to be moving and the Earth will seem to be still, even though we know that the Earth is moving very quickly and the moon is still.

Even if we were to say that beliefs which are solely about an individual item are theories (for example, the belief that one is seeing a drawing of a rabbit in front of one), Fodor’s view seems to provide an explanation of the evidence which fits at least as well as explanations involving theory-Iadenness, and which can more easily explain recalcitrant illusions. Of course, if we call any kind of low-level cognitive processing theoretical, it is true but trivial that all experience is permeated by theory.

I should explain here that in defending Fodor I am not trying to defend the thesis that experience is totally unstructured, or that our understanding of it uses no conceptual categories at all. In Fodor’s fuller account, the higher processing module contributes terms which are hierarchically organized into families of natural kind terms, ordered from the very specific to the very general. Some of the terms in these hierarchies are roughly midway and Fodor calls these ‘basic categories’. For example, ‘bird’ is halfway between ‘animal’ and ‘black crow’. According to Fodor these concepts are phenomenologically salient in the sense that they are triggered by encounter with their instances. Confronted with the average bird we will naturally see it as a bird. Basic categories are observational in the sense that normal unassisted subjects will recognize things as belonging to those groups. It is important to stress three things: first, Fodor thinks it is a matter of empirical research as to which categories are basic. Second, the language of basic categories is not an impoverished language which merely describes experiences, but a realist one in the sense that using that language and perceiving items involves one in assuming the existence of space, time, matter, etc. Third, using that language does not presuppose any particular theory about the universe or the nature of space, time, matter, etc.5

Fodor puts a good case for saying our everyday experience of the world yields something which may be called the Basic Observational Fragment of sense perception. It is basic in the sense that it provides a common ground to which various theorists can appeal to test their theories. It i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction

- 1 Theory and Observation

- 2 Induction and Probability

- 3 Popper and Mill: Fallibility, Falsification and Coherence

- 4 Revolutionary Change and Rationality: Kuhn and his Rivals

- 5 Relativism and the Value of Science

- 6 The Sociology of Knowledge and Feminism

- 7 Realism and Instrumentalism

- References

- Index