![]()

PART I

AN INTRODUCTION TO CHILD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

![]()

| INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS CHILD HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY? | 1 |

Covered in this chapter

• Definition of child health psychology

• The psychosocial context of child health

• The developmental context of child health

• The mind–body link: from medieval to modern-day views

• The mind–body connection in modern times

• Health-related behaviour and social cognition models

• The changing face of health threats

• A worldview on child health

• Communicating health

Interest in the promotion and enhancement of health in children reflects a central human drive to protect and nurture, often in the hope of improving life chances and well-being for future generations. In this chapter, I begin by defining what is meant by child health psychology, and look at where it fits within the framework of psychology, health and medicine. I then start to consider what, how and why psychological factors might be important in relation to physical health in children and the impact of psychological factors across the different stages of development from infancy to adolescence. The role of psychological influences on physical health in children is introduced from an historical perspective in order to set in context our modern-day approach. Biomedical advances are discussed in the context of past, present and future physical health threats and challenges to child and adolescent health. Whilst this book focuses on health in the Western world, we will also consider threats to health in developing countries and contrasts between health threats across the globe.

DEFINITION OF CHILD HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY

In its broadest sense, the discipline of health psychology as defined by the British Psychological Society’s (BPS) Division of Health Psychology (DHP) relates psychosocial factors to physical health and illness in order to (i) promote and maintain health; (ii) prevent and manage illness; (iii) identify psychological factors which contribute to physical illness; (iv) improve the health care system; and (v) help formulate health policy (see www.health-psychology.org.uk). The term ‘psychosocial’ refers to any combination of psychological and social factors and their interplay. Psychological factors include the way a person thinks (cognitions), their coping responses, attitude and their temperament or personality (sometimes termed individual differences). Social factors include the social resources available to an individual, which are embedded within their culture and position within society and within their more immediate social network.

Child health psychology, then, is the specific application of health psychology research and practice to physical health in children, as well as the implications and applications of psychosocial influences during childhood development on subsequent health in adulthood. In this book, I use the term ‘childhood’ to cover the full age range of child and adolescent years from zero through to 18 years old, with specific age groups highlighted as different issues are covered. In some chapters, the boundaries of this age range are extended at either end of the spectrum in order to consider prenatal health issues during pregnancy or the transition from adolescence to adulthood and what this means for access to health services, as well as the implications of childhood experience on adult health in middle and older age. As the focus throughout this book is on biopsychosocial interactions, important questions relate to how the physiological response systems of the body might be shaped, both positively and negatively, by early life experience, and how these influences map onto health during childhood and through to adulthood. This begs the question of what the potential might be for interventions to repair or ‘normalize’ the response systems in cases where early psychosocial experiences have created a physiological imbalance. These are not easy questions to answer, and research in this area has a long way to go, but we can go part way in answering some of these questions based on research findings to date (as well as debunking some more spurious ideas that have developed along the way).

In many respects, these are exciting times for health psychologists interested in child health. An important change in perspective, or paradigm shift, is beginning to emerge across the many related scientific disciplines of health and illness, which reflects a greater understanding of the impact of early life adversity on physical health right across the whole gamut of different life stages. This gives recognition to the idea that early life experience from conception through to childhood can have a large influence on health outcomes throughout the lifespan or course of life. I will return to this life-course idea throughout the book but, to introduce it here, it is based on an increasing amount of evidence which has found a whole range of adult health conditions to be associated with childhood experiences. The influence of psychosocial factors on children is central to health psychology and related disciplines because of the lifespan implications. The full circle of implications is important, considering not just childhood itself but the longer-term perspective into adulthood and across the lifespan, as well as prenatal influences on child health.

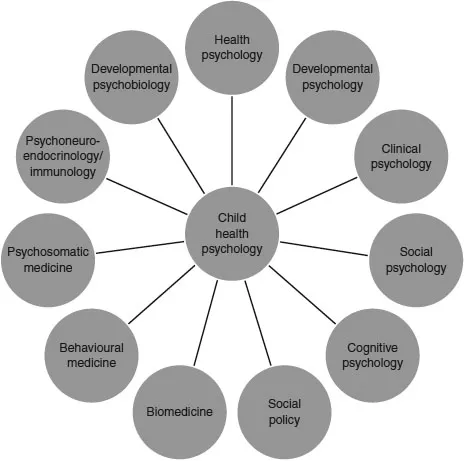

There are also several overlapping disciplines specific to childhood that directly acknowledge psychosocial influences on physical health, including developmental psychology and the field of developmental psychobiology, as well as other broader fields, such as clinical psychology and biomedicine, from which the topic of child health psychology draws. Figure 1.1 gives an idea of these disciplinary links and influences which I will be drawing on throughout this book. It is by no means intended to be exhaustive but may be useful to consider whilst reading the following chapters. Think of it as a conceptual drawing board rather than a definitive conceptual model: you may want to add further areas or links between the disciplines given.

In connection with this, in recent years there has been a sea change in the use of positive terminology relating to ‘wellness’ rather than the more historical terminology of ‘illness’ and ‘ill health’. This, of course, fits with major advances in medical technology and pharmaceutical development. This shift has, on the whole, been presented as an optimistic paradigm change. Yet, at the risk of appearing cynical, this could, in part, be due to a reluctance to face the negative side of ill health realistically. The positive or optimistic approach of health psychology is, first and foremost, to recognize the negative impact and turmoil brought about by ill health and to use this knowledge and understanding to build prevention programmes and interventions where possible, but also to provide care and support in the face of chronic or terminal illness.

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL CONTEXT OF CHILD HEALTH

There are two main concepts that I want to introduce in relation to the psychosocial context of child health: these are the concepts of social support and socioeconomic status. The concept of social support encompasses both psychological and social aspects: for example, the size of a person’s social network, or having a family member or friend who can offer emotional support (someone to talk to or share emotions with), financial support (providing money for a school trip) or practical support (ensuring a safe lift home from a late-night party). These latter two types of support may be practical in origin, but whether or not help is available or perceived to be available is also likely to be bound up with emotional meaning and significance, as it is for emotional support itself. As will become obvious, harnessing the power of social support is an important tool in interventions to improve physical health outcome. The concept of social support is discussed in detail in Chapter 2; the methodological aspects of social support assessment are covered in Chapter 3; and various forms of support are mentioned throughout the remaining chapters.

The second of these concepts, socioeconomic status, is the term used for an individual’s position in society and is measured in a number of different ways, including household income, a person’s marital status (or for children that of their parents), access to/level of education, family size, or whether or not a household owns a car. In particular, socioeconomic status is relevant in situations where childhood experience has its roots in social and economic disadvantage or poverty. Childhood socioeconomic status has been implicated in an impressive array of examples of causes of death (mortality) during adulthood and the occurrence of a variety of adult health conditions from depression to cardiovascular disease (Braveman and Barclay, 2009).

The strength of this association between low socioeconomic status and poor physical health has been demonstrated across a range of racial groups and ethnicities. Using family income as the measure of socioeconomic status, Braveman and Barclay (2009) illustrate the consistent nature of socioeconomic status in its impact on health in a sample of children aged 17 years and under in the United States. For each of their three categories of race/ethnicity, a clear pattern was found which indicated that the lower the family income, the poorer the physical health of the children. Within this income–health pattern, they also demonstrate variability in health outcome between the race/ethnicity categories, with Hispanic children showing a larger proportion ‘in less than very good health’, followed by black/Hispanic children, and white/non-Hispanic children showing a larger proportion in good health.

It has long been accepted that investment in early education is a key area for reducing social deprivation and breaking the cycle of poverty, and extensive education research exists in this area. This has emerged from an increasing awareness and acceptance of the effects of early life stress on physical health outcomes, coupled with the understanding that socioeconomic disadvantage (i.e., lower income, poorer education) can influence health via the numerous potential stressors that it may create. Individuals living in a poorer environment are more likely to experience stressful events relating to various disruptions in their personal, family, community, or school life, including personal maltreatment, parental conflict, and violence in their neighbourhood (Shonkoff et al., 2009). There is increasingly compelling evidence for a process of ‘biological embedding’ in which the experience of early adversity primes the physiological systems, setting the scene for vulnerability to negative health outcome following subsequent life stress (Shonkoff et al., 2009). This is a theme I will return to later as we consider the theories and mechanisms by which this might operate (Chapter 2), how this can be applied to the experience of intra-uterine stress during pregnancy (Chapter 4), and the effects on childhood health and illness later in life (Chapter 5). Of course, just as low socioeconomic status per se does not cause ill health, disease and illness are not solely the domain of those with low socioeconomic status. Indeed, the effects of stress and anxiety on underlying physiological mechanisms associated with ill health are often a curse of the middle classes in the developed world. Disease and illness are seen throughout the socioeconomic classes, but having low socioeconomic status during childhood carries with it an increased chance of ill health, particularly for certain types of conditions as described above. Gaining an understanding of how and why these health differences exist, and the interactions between these social factors and psychological factors, is of much interest to health psychology and related disciplines.

The implication of this life-course perspective is that early intervention is essential if health disparities later in life are to be minimized. The factor that has enabled this to receive attention and move the field forward is the potential economic impact for health-care provision. The current thought is that providing health investment in adult care is expensive and limited, whilst investment in improving the physical and social environment of children will pay dividends through a reduction in their health-care needs throughout their life. This perspective goes beyond the idea that investment in childhood poverty will merely improve health-related behaviours such as diet and exercise, important though they are, to the notion that reducing stress in early life will physiologically alter the developing child and consequently improve their health outcome over time as well as that of future generations. This may all sound rather far-fetched, and it is unrealistic to think that inequality, stress and adversity can be eliminated, but aside from the very real practical improvements in health outcome, the theory and supporting evidence for alterations in this way provide a sound theoretical basis for understanding the powerful mechanisms behind mind–body links and their central importance in the application to child health.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL CONTEXT OF CHILD HEALTH

It is vital to consider the developmental context in which health and illness are set. There are many excellent developmental psychology textbooks which document the biological, cognitive, language and social d...